Original author: Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas

Original published date: 6th March 2014

Updated by: Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas

Update date: April 2025

Review date: April 2027

The care management of cancer consists of healthcare professionals from different disciplines. Their role is to discuss the care plans and ensure each patient receives the appropriate selection of a treatment regimen where the type of cancer is imperative (World Health Organisation, 2025a). Medical specialists such as oncologists whose expertise lies in diagnosing and treating various cancers. Radiologists who specialize in performing and interpreting scans and X-rays and Surgeons who perform surgical procedures with precision to maximize survival rates. Nurses take care of the daily needs of each patient by giving medications, temperature and blood pressure checks, hygiene, food, and aspects throughout their treatment journey. The oncology pharmacists specialize in cancer medications. Scientists analyze the blood, urine, and other specimens for DNA, cells, proteins, tumour markers, and infectious agents. Other roles are also vital but are overlooked, the porters who send patients to do tests and scans. Receptionists who send referrals and appointment letters. Domestic cleaners who ensure the wards and offices are hygienic to work in to lower the rate of preventable infections. According to the National Institute of Care and Excellence (NICE), the treatment protocol is vital for a better prognosis and therapeutic response.

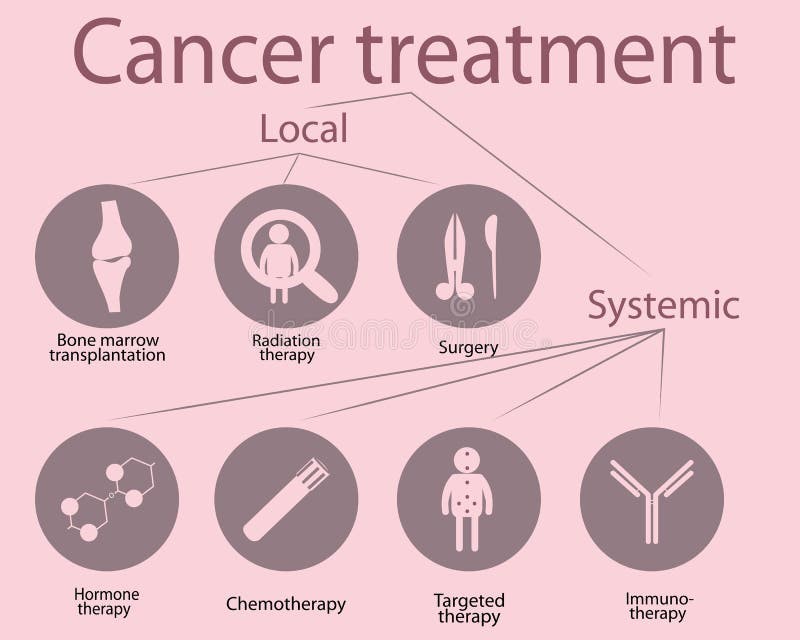

Understanding the rationale for cancer treatment is necessary and primarily is a curative approach in primary treatment to ensure the complete removal of the tumour or the killing of all cancer cells. Cancers that are in sensitive locations may need chemotherapy or radiotherapy but, commonly, surgery is done in the early stages. Neoadjuvant refers to chemotherapy given before surgery to make an effective outcome. Adjuvant treatment aims to kill any remaining cancer cells post-surgery to prevent the cancer from spreading (metastasis) or re-occurrence (relapse). This can be done using chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biological and hormonal therapy.

Palliative care treatment aims to relieve symptoms from the cancer or side effects caused by therapy to improve the quality of life for patients with terminal cancers. A people-centered approach to patients offers support and comprises medical intervention and well-being within hospital settings and the patients’ broad lives within the community (World Health Organisation, 2025a).

Some cancers, for instance, breast, cervical, bowel, and oral cancer have higher chances of survival rates when detected early, whereas, other cancers for example, cancers of the blood, thyroid, and testicles have a higher likelihood of survival even if metastasis at presentation occurs if appropriate treatment is provided (World Health Organisation, 2025a; Cassidy et al., 2010).

Depending on the stage, grade, location, and type of cancer and factors such as age, family, and clinical history, a care plan can be developed. Combined therapy aims to raise the ‘fractional cell kill’ to improve the overall therapeutic response of the tumour by increasing the dose of cytotoxic effects. During the early stages of cancer, surgery is the principal method for localized tumours. It has an advantage that surpasses radiotherapy in cases where the morbidity of treating tissues without the primary tumour is less (Cassidy et al., 2010). However, some types of brain cancers cannot be operated on straight away because the site where the benign cancer is grown is sensitive and complicated and should be monitored for signs of activity before operating even if detected early. In late-stage cancers, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are given to increase effectiveness. For example, radiotherapy can be used to treat the primary cancer and then surgery can be used to remove the lymph nodes if it has not been fully removed. Lymph nodes are filtering structures that can trap cancer cells and prevent metastasis (Agrawal, 2023).

Chemotherapy

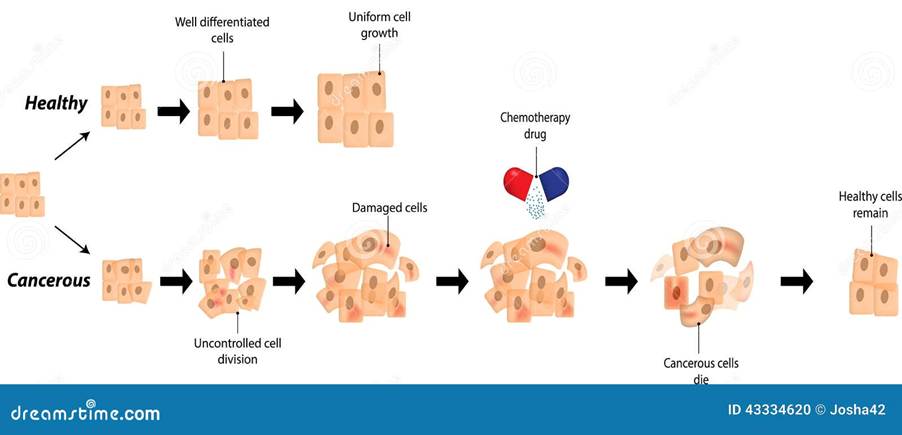

Chemotherapy uses chemicals to kill cancer cells so they are unable to divide and grow. A single chemotherapeutic (monotherapy) or combined regimen depends on the type, stage, and grade of cancer. A critical determinant of how effective the chemotherapy would work is the immune system where depletion of cells that promote immune response abrogates its purpose or advantage (Tilsed et al., 2022). Chemotherapy can be classified based on the mode of action, source (natural or synthetic), and propensity to be cell cycle or phase-specific (Cassidy et al., 2010).

The two main types of chemotherapy are curative and palliative. Curative chemotherapy aims to cure cancer completely to make other treatments such as radiotherapy work appropriately, lower the risk of cancer returning, and treat non-cancerous tumours (benign) – please see Figure 1. If given before surgery, it is called peri-operative chemotherapy and there is evidence of long-term survival in patients with localized tumours of the oesophagus (food pipe) who had chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer (Tilsed et al., 2022). The purpose of palliative chemotherapy is to shrink the size of the cancer, slow the spread, or relieve symptoms if unremoved by surgery or treatable. It is commonly performed in advanced cancers to improve the quality of life.

Figure 1: The effect of chemotherapy on cancer growth

However, there is heterogeneity in the chemo-responsiveness of patients with the same type of tumour, and this is not well understood of the outcome. For instance, localized testicular cancer had a small percentage of patients who did not respond to adjuvant therapy. Thirty percent of patients who had combined therapy carboplatin and paclitaxel with radiotherapy responded but twenty percent had no response (van Hagen et al., 2012). Lack of response towards chemotherapy was also observed in other types of cancer, for instance, patients with solid tumours such as nonsquamous cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colon, breast, pancreatic, and mesothelioma. However, fourty percent of patients with mesothelioma had a partial response followed by progression and sixty percent of colorectal cancer patients responded. Cancers who had complete responses were patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (20-40%) and SCLC (1-5%) (Tilsed et al., 2022). Patients with germ cell tumours had a durable response of 90%. A complete durable response rate is the continuous response that initiates within 12 months of treatment and lasts six months or more (Kaufmann et al., 2017). A possible explanation for the variation in response is the expression of mutated proteins between cells and its stochastically rendered chemotherapeutic resistance (Tilsed et al., 2022).

How is chemotherapy administered?

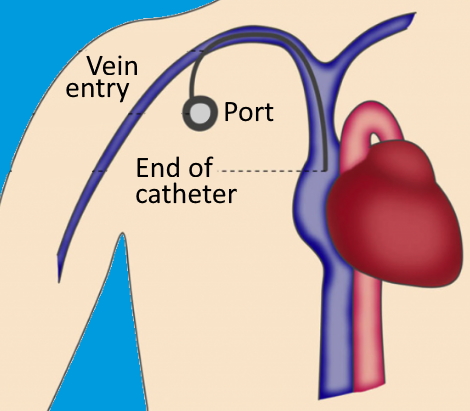

There are several ways in which chemotherapy is administered, oral, intravenous (IV), catheter, pump, port, injection, abdomen, intrathecal, intraarterial, and topical. Intravenous application directly enters the vein in the hand or lower arm and is the most common way of all types (National Cancer Institute, 2022). IV chemotherapy may be given via other techniques: catheter, pump, and port. A catheter is a thin and soft tube where one end is positioned in a large vein in the chest via a small round disc called a port. The port is surgically placed under the skin before starting treatment and kept until the end of the treatment course. The other end of the catheter is outside the body until the end of treatment. The port can give alternative chemotherapy medication for a day at minimum and be able to draw blood (National Cancer Institute, 2022). Please see Figure 2. The pump is external (outside the body) or internal (under the subcutaneous skin) and monitors the quantification and dose chemotherapy is passed through the catheter or port to help manage treatment outside of the hospital (National Cancer Institute, 2022). This implies that chemotherapy can be done at the hospital, home, outpatient clinic, and other settings.

Figure 2: The catheter in the subclavian vein and port is positioned for the influx of chemotherapy

There are other administrative methods of chemotherapy: oral medications are swallowed as capsules, liquids, or pills (National Cancer Institute, 2022). Intrathecal injections between tissues that cover the brain and spinal cord. It is entered into the spinal canal or subarachnoid space to access the cerebrospinal fluid. This is useful for chemotherapy, pain management, or spinal anaesthesia where narcotics could be added for pain relief. Another form of injection is aimed at the intramuscular area of the arm, thigh, hip, or under the skin in the arm leg, or abdomen (National Cancer Institute, 2022).

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is where a small cut/incision is performed onto the stomach/abdomen directly to the peritoneal cavity where the intestines, liver, and stomach are situated. A tube known as a catheter is entered through to remove the fluid called ascites. The ascites is what causes the abdominal wall to swell. The chemotherapy is then entered via the catheter. It is not commonly done and is given in cases where there are signs that cancer has spread into the stomach wall and there is swelling (National Cancer Institute 2022). Other methods of administration of chemotherapy include the artery (intra-arterial) and topical (cream rubbed onto the skin).

Chemotherapy is prescribed in a cyclic manner where each cycle accounts for four weeks. A cycle is the period chemotherapy is given i.e. daily for one week followed by three weeks without chemotherapy. The rest period ensures the body is recovering and new and healthy cells are synthesized (National Cancer Institute, 2022). Chemotherapy may be combined with other conventional treatments but has several principles: each drug should have a different mechanism of action and function in a distinct part of the cell cycle. No overlapping toxicity nor resistance patterns are shared (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Chemotherapy may cause side effects and must inform the doctor who will alter the chemotherapy schedule. Changes to diet may occur as cells that line the mouth and intestines can be affected. The patient’s clinical outcome is monitored using physical examination, blood tests, and scans, namely computer tomography (CT), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (National Cancer Institute, 2022).

Mode of action of chemotherapy

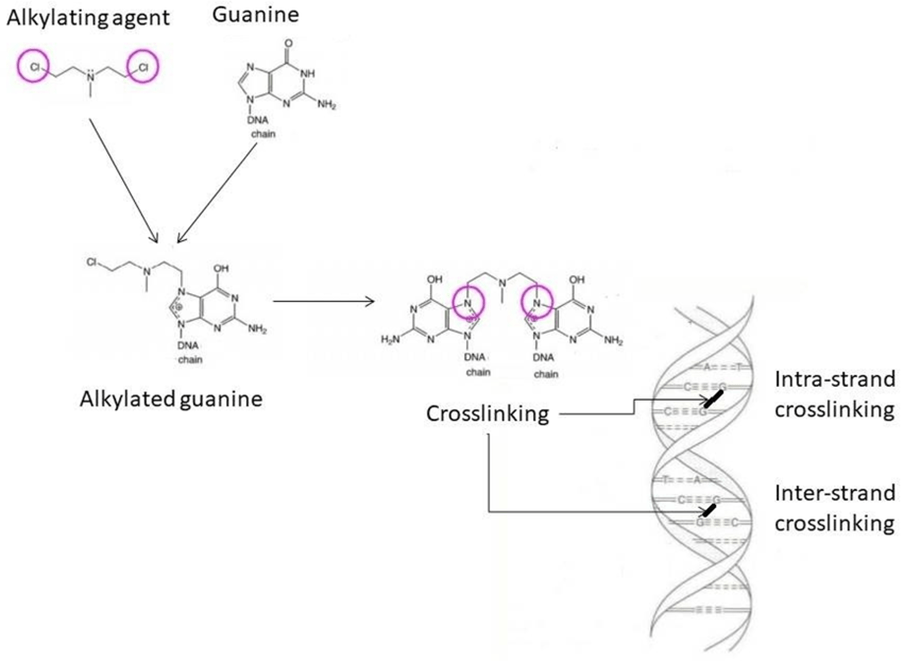

DNA alkylating agents are anti-proliferative drugs and have traditionally been used the longest in cancer care several groups in this class are similar in mechanism of action but vary in toxicity and clinical activity. The first mode of action is some agents can bind covalently to DNA via alkyl groups to form single and double-stranded breaks – please see Figure 3. This can affect RNA, and macromolecules (e.g. proteins and lipids) and create toxic products (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010). Key examples of this group are cyclophosphamide, mitomycin C, and streptozocin. They are extensively used to treat blood cancers (leukaemia and lymphoma) and solid cancers. Cyclophosphamide lacks non-hematological toxicities and can be used at a high dose. Mitomycin C can also facilitate chemo irradiation to increase sensitivity to radiotherapy and is also used to treat breast, lung, gastrointestinal and anal cancer (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Another group of DNA alkylating agents intercalate with DNA to form reactive oxygen species (ROS) which increases oxidative stress and promotes further mutations. Key examples of the second group include anthracyclines e.g. doxorubicin and its derivatives. The main target for anthracyclines is the enzyme topoisomerase II which regulates the topology of the DNA helix and binds to DNA during cell division forming a complex. The cleaving complex creates nicks in DNA and as a consequence, DNA is released and the two strands of DNA are rejoined. Thus, DNA alkylating agents disrupt the complex, causing double-strand breaks, and induce cell death in non-proliferating cells. However, there is a risk of cardiotoxicity when administrating Doxorubicin if free radicals are formed in the heart where the immune system is less active.

Other cytotoxic agents also target topoisomerases and are referred to as topoisomerase II inhibitors. A key example is etoposide which is used to treat germ cell tumours, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and adult and paediatric malignancies (Cassidy et al., 2010).

The third group of DNA alkylating agents forms inter or intra-strand DNA crosslinks and ROS by binding directly to DNA and altering the DNA template. This can arrest cells in the G1-S phase of the cell cycle to stop DNA replication, repair, and cause cell death (apoptosis) (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010). Key examples include platinum-based drugs: cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and carboplatin. Carboplatin is less toxic than cisplatin. Oxaliplatin is commonly used to treat upper gastrointestinal and colorectal cancer adjuvant and advanced due to its broad spectrum activity.

Figure 3: The mode of action of DNA alkylating agents (Schjesvold and Orial, 2021). The nitrogenous base, guanine, undergoes alkylation and causes the opening of the guanine ring and base pairing in DNA. Intra and interstranding crosslinks effects transcription of genes and replication of DNA

One of the anthracyclines, doxorubicin is also part of another chemotherapy class called anti-microtubules. Antimicrotubules have two groups: taxanes and vinca alkaloids. Taxanes bind to a protein called α-tubulin that polymerizes to form microtubules which stop their movement and function. The normal function of microtubules preserves the shape of the cell and its locomotion: separation of chromosomes during anaphase in mitosis and transport of organelles – please see Figure 4. This alters cell signaling, cell progression, cell migration, and invasion. Key examples are paclitaxel and doxorubicin. Paclitaxel can be combined with cisplatin or carboplatin to treat ovarian cancer. Paclitaxel is also used to treat breast cancer when combined with doxorubicin (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

Vinca alkaloids depolymerize microtubules, destroy mitotic spindles at high levels, and block mitosis at low levels. Key examples are vinblastine, vinorelbine, and vincristine. Vincristine is prescribed for blood cancers, paediatric and small cell lung cancer. Vinblastine for lymphoma, germ cells, Kaposi sarcoma, and breast cancer. Vinorelabine for NSCLC and breast cancer. Vina alkaloids are combined with cisplatin to treat lung cancer. It is combined with doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil for breast cancer (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

Figure 4: The structure of microtubules and the stages within mitosis where during anaphase the chromosomes are seperated (Creative Commons, 2025)

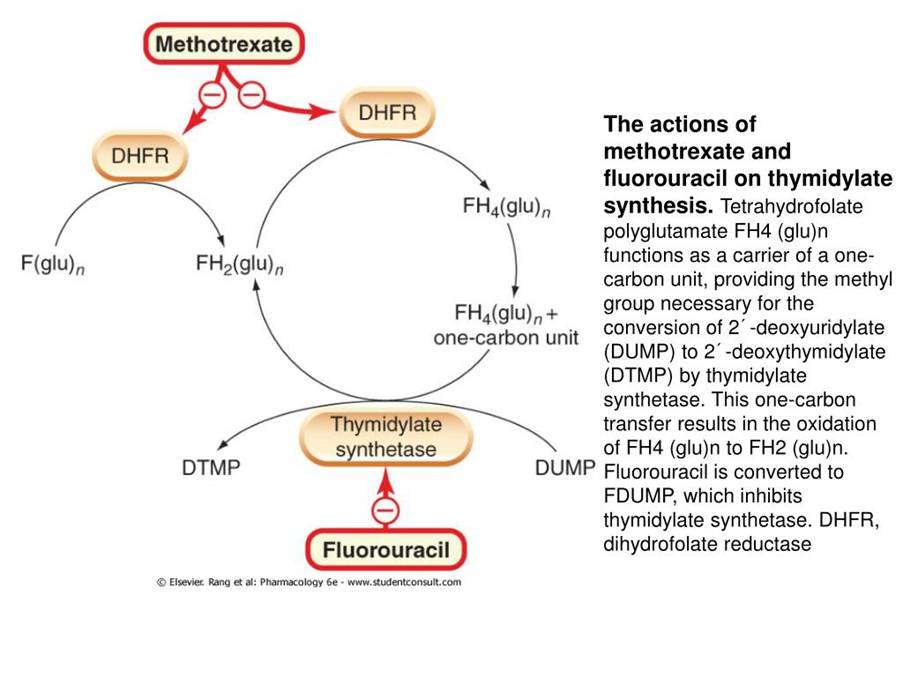

Another chemotherapeutic class of drugs is antimetabolites which affect normal cellular metabolism, DNA synthesis, and replication. There are several groups in this class. The enzyme thymidylate synthase (TS) is involved in the synthesis of thymidylate pyrimidine. A key example of antifolates is 5-fluorouracil which inhibits TS and then interacts with the folate binding site. It also inhibits RNA synthesis. It is commonly used in breast, gastrointestinal, and head and neck cancers. Another group of antimetabolites is cytosine analogues e.g. cytarabine and gemcitabine. Cytarabine is incorporated into DNA and inhibits DNA polymerase phospholipid synthesis and ribonucleotide reductase which stop DNA replication, elongation, and repair (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010). Methotrexate also binds to DHFR – please see Figure 5.

Figure 5: The cytotoxic mechanism of antimetabolites (Creative Commons, 2025)

Factors affecting the sensitivity of chemotherapy

Multifactorial mechanisms circumvent drug resistance. Multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) acts as an energy-depending pump causing drug efflux; the drug enters via diffusion and active transport and removed by transporters. Another drug efflux pump with the same function is the P-glycoprotein. Overexpression of mutated tumour suppressor proteins, the guardian of the gene TP53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) can dysregulate apoptotic pathways. This is commonly found in lung, breast, and colorectal and reduces sensitivity to chemotherapy (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

Another mode of mechanism is cancer stem cells that can self-renew and have the ability to grow and metastasize. This confers resistance to chemotherapy due to slow growth, anti-apoptosis, modulated ROS, and expression of drug efflux pumps (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010). Patients who have low density of blood vessels have poor chemotherapy response.

Evading DNA damage through repair pathways, for instance, mismatch, base excision homologous recombination, and increased excision repair genes prone to platinum drug-based resistance (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

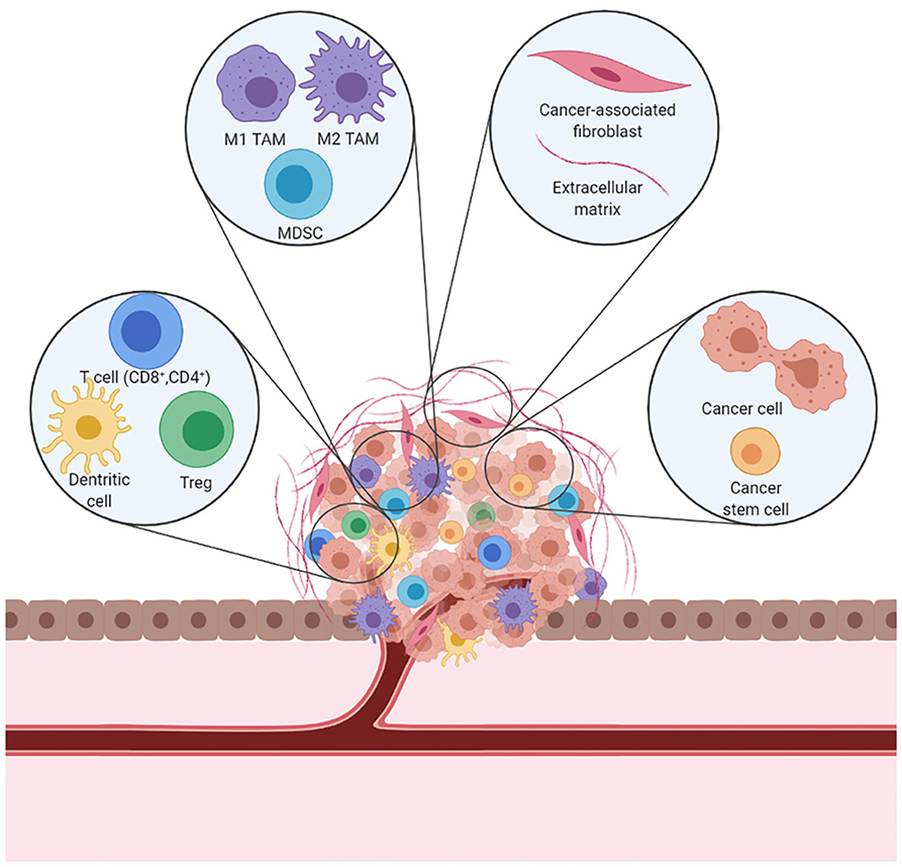

A tumour microenvironment (TME) infiltrated with immune cells such as T cells (CD8+), mediators of inflammations such as interferons (IFN), and Tumour necrosis Factor-alpha (TNFα) can affect chemosensitivity response – please see Figure 6. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) can induce chemotherapy resistance by secreting TGF-β, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) that collectively promote tumour progression and enhance invasion, angiogenesis and metastatic potential and other hallmarks of cancer and chemotherapeutic resistance transitioning the TME to immunosuppression. It can also form fibrotic tissue as a physical barrier around the tumour to limit drug effectiveness and availability (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010). This highlights that despite the side effects of chemotherapy leading to leukodepletion and immunosuppressive, it can limit the efficacy of chemotherapy (Tilsed et al., 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

Moreover, interferons elicit a cytostatic response and modulate the expression of oncogenes to increase the activity of macrophages, T cells, and natural killer cells. It is exhibited in cancers of the carcinoid (small intestine), renal (kidney), and blood cancers (hairy cell, chronic myeloid leukakemia, and malignant melanoma) (Kciuk et al., 2023).

Figure 6: The tumour microenvironment (Creative Commons, 2025)

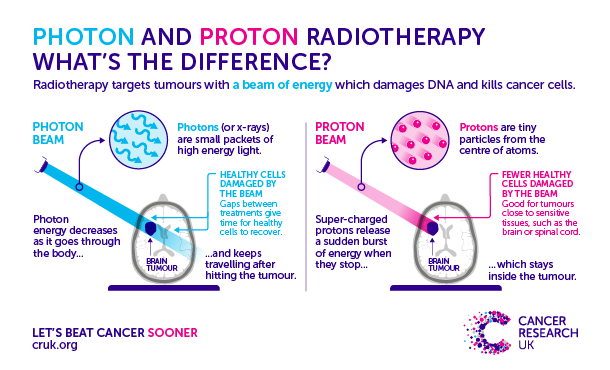

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the application of radiation or high-energy rays such as X-rays and gamma rays to kill cancer cells or relieve symptoms and improve quality of life (Cassidy et al., 2010). The unit for radiation is Gy which corresponds to the energy absorbed per unit mass joules/kilogram. The principle method involves X-rays passing through living tissue, the energy is then absorbed causing the molecules to become ionized and the fast-moving electrons and free radicals can proceed to damage the DNA (Cassidy et al., 2010). This results in the loss of functional cells by apoptosis and loss of cell division.

The dual factors, dose and time affect the delivery of results. The types of cells that are highly radiosensitive are white blood cells and germ cells. For instance, patients with lymphoma and seminoma have 30 to 40 Gy which is 50% less than what is required for carcinomas 60 to 70 Gy. This is followed by epithelial cells that line the organs with moderate sensitivity. The nerve cells and connective tissue are most resistant hence why patients with glioma and sarcoma have low success rates (Cassidy et al., 2010).

The rate of cell renewal varies from days to even years. For example, a single dose of radiation of 10 Gy to the abdomen/belly and the lining of the intestines (mucosa) can be depleted within a few days. However, there are several advantages to large daily fractions. Fewer attendance, spare resources, faster response, and lower risk of repopulation of cells. Nevertheless, it limits the total dose being safely delivered, lowers chances for reoxygenation of cells that are hypoxic (low oxygen), and magnifies the risk of normal tissue being damaged in later years (Cassidy et al., 2010). Hypoxia cells are two to three-fold less sensitive to radiotherapy than oxygenated cells and are linked to abnormal blood supply.

However, if the dose was divided across five days known as fractionation where 2 Gy is given per day. It helps to ensure the safe delivery of a higher total dose of radiation increases cancer cell kill and spares damage to normal tissue using maximal total dose. There is a 6 to 8-hour interval between fractions enabling repair to damaged normal tissue. There are several disadvantages: demand for resources, repopulation of cells growing rapidly, prolonged acute reaction, and risk of sore mouth. This emphasizes the severity of side effects depends on the total dose of radiation and the length of delivery time imposed on radiotherapy (Cassidy et al., 2010).

In contrast, late effects of radiotherapy in slowly proliferating tissues. For instance, the lung, kidney, liver, and central nervous system are not restricted to the slow renewal of cells. Late changes can happen years later in the skin. Severity depends on the total dose of radiation and the dose per fraction (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Moreover, radiotherapy-induced DNA damage may lead to the development of new cancers between 5 to 40 years. For instance, leukaemia is 6 to 8 years after radiotherapy whereas solid cancers e.g. thyroid and breast may occur after 10 to 30 years (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Types of radiotherapy

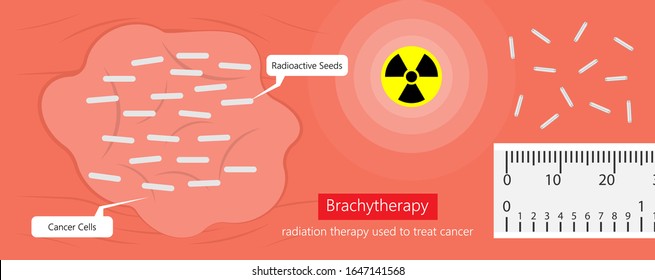

There are two main types of radiotherapy: internal and external. Internal radiotherapy otherwise known as brachytherapy is the injection of radioactive substances inside the body. This is commonly used as a sole treatment for small early-staged cancers, adjuvant post-surgery, or after external radiotherapy to kill any pending cancer cells (Caffasso, 2024). Examples of cancers used are: gynaecological, breast, lung, gastrointestinal (rectal, liver), head and neck, eye, and skin cancers (Caffasso, 2024).

Brachytherapy is a painless and safe procedure that involves radioactive material e.g. ribbons, wires, seeds, or pellets emitting high-frequency waves to damage DNA in cancer cells. The procedure itself could be temporary or permanent. Temporary brachytherapy involves placing the radioactive material inside a catheter for a short period. If permanent, it involves seeds inside or near the tumour that lose radioactivity over several weeks or months and may stay in the body permanently – please see Figure 7 (Cassidy et al., 2010). If the radiotherapy enters via the intracavity route (body cavities), it is commonly done for uterine (cervical), lung, oesophageal, and bile duct cancers. The types of cancers where radiotherapy is entered into the tissue (interstitial) are prostate, breast, head and neck, and anal cancer (anus). Radiotherapy given on the surface is for cancers of the skin and eye (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Figure 7: The presence of radioactive seeds in cancer cells during brachytherapy.

The preparative steps are given to the patient by the doctor. The bowel should be emptied a few days before. To avoid drinking fluid after midnight on the day of the procedure. The procedure takes place in an operative room. Two types of anaesthesia could be given to the patient: general and local. General anaesthesia puts the patient to sleep whereas, local anaesthesia aims to make the patient numb. The catheter is added to the body where the radiation enters as a non-radioactive metallic capsule. This may take a few minutes or is permanent. The patient remains in the hospital for a few hours or overnight.

Research presents that brachytherapy is safe but efficacy is dependent on disease sites. Patients with breast and liver cancer are more effective than prostate cancer (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022).

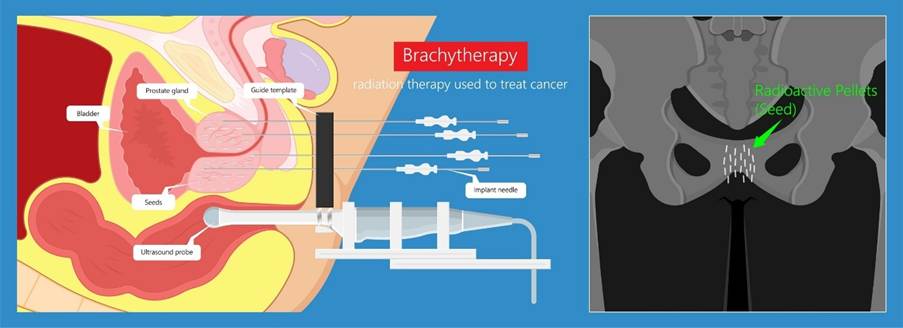

Brachytherapy of prostate cancer illustrated in Figure 8. In 618 patients with liver cancer, the dose ranges between 8 and 25 Gy, median follow-up 11 to 33 months, and local rates (LC) between 37% to 98%. Toxicities were found in three patients (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022). Among patients with breast cancer, 268 patients had doses between 16 to 20 Gy. The median follow-up was higher than liver cancer at 24 to 72 months. The LC rate was 100% and toxicities ranged between 0to 6% (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022). However, for 1474 patients, doses ranged between 19 to 21 Gy and the median follow-up was from 20 to 72 months. The control of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) post-treatment ranged from 65 to 94% and recovery treatment from 5 to 84%. Toxicities for prostate cancer were similar to breast cancer (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022).

Figure 8: Brachytherapy for a prostate cancer patient

Brachytherapy is a versatile technique that delivers highly concentrated doses of radiation to small target tumour volume. This form of local control limits the dose to surrounding organs that are at risk (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022). There is a shorter duration of treatment time (2 to 7 days) which takes advantage of the rate of repair. Hypoxic cells are resistant to radiation but this is overcome through reoxygenation during low dose rate of radiation to increase its radiosensitivity. It is cost-effective and improves efficiency by safely delivering single-fraction doses of radiation (Kazemi, Nadarajan, and Kamrava, 2022; Cassidy et al., 2010).

However, like every procedure, there are risks. The radioactive seeds may move to the lungs and there are gastrointestinal side effects, for instance, rectal pain or inflammation (proctitis) and variation in the stool/poo texture (constipation, diarrhoea). Urological side effects may arise, for instance, burning sensation, stricture of the urethra, blood in the urine (haematuria), and the state and movement of urine (frequency, incontinence). Other side effects include gynaecological, for instance, erectile dysfunction and fertility issues. Tiredness, skin irradiation, redness, warmth, swelling, hardness, and bone fraction may also occur. Risks will also increase if the patient is a smoker due to the effect of radiation. Following the procedure, the patient may be able to return to regular activities within a few days if a temporary procedure was done, however, if the permanent procedure, limited contact with small children and pregnant women. The doctor needs to be informed of any medications the patient takes, for instance, blood thinners e.g. aspirin, analgesia like Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) e.g. paracetamol, and antibiotics e.g. penicillin. An increase in urine output may occur especially those given for prostate. Collectively, these side effects may appear many but are less than those experienced with external radiotherapy.

Other contributing limitations are the unsuitability of larger tumours or surrounding lymph nodes that will undergo irradiation due to the source emitting gamma rays. However, brachytherapy may be given after external radiotherapy or chemotherapy. In addition, radiation dose falls rapidly low from sources (Cassidy et al., 2010).

External beam radiotherapy

External radiotherapy is where a device or machine contains the radiotherapy and targets the cancer inside the patient – please see Figure 9. However, this depends on the site. Skin and ribs are treated by X-rays of a low energy range of 80 to 300 kilovolts (kV). It cannot be used for deep-seated tumours such as the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis that require megavoltage photons e.g. cobalt (co-60) emitting gamma rays of energy 1.25 meV (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Low energy usage also has other disadvantages, for instance, the delivery of a higher absorbed dose to skin and bone than soft tissue. It is avoidable at higher energy because a higher dose is delivered to the skin, and is spared; it is feasible treatment in forms of direction (Cassidy et al., 2010). Sensitive areas such as the head, neck, and lungs are given high doses with precision.

In preparation for external radiation therapy, the radiation oncologist will begin with the planning session referred to as simulation. A discussion with the patient about his or her clinical history, test results, and physical examination is the initial step. The target area to be treated is highlighted when the patient is positioned on the observation table. Imaging scans i.e. computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) define the target area to be treated with the radiation beam. It may involve a contrast agent to improve the quality of the imaging. This target area is referred to as a treatment field or port.

Once agreed to continue with the process, the high energy X-ray radiation is delivered directly to the tumour from outside the body with local control using a machine linear accelerator. The beams are much stronger than a typical X-ray. This is achieved by creating a special mold, mask, or cast or making semi-permanent or permanent dots to ensure the dose is consistently placed in the same position. After treatment, permanent dots are removed via laser (American Cancer Society, 2025).

If a fractionated approach is applied, radiation is given five days a week for five to eight weeks. Each session took 15 to 30 minutes because it included time to set up equipment, position, and dose delivery. The recovery breaks help normal cells to proliferate. The total dose and number of treatments depend on the type, size, site of the cancer, and general health (American Cancer Society, 2025).

Figure 9: External beam radiation for a lung cancer patient.

There are multiple subtypes of external radiation therapy that all aim to focus on the cancer and lower damage to normal tissues. Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) delivers radiation beams from multiple directions to match the shape and size of the tumour in a defined region. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) allows stronger doses to be used and stronger intensity of the beams. One of the subtypes of IMRT is Helical tomotherapy where small beams of radiation are given precisely.

Stereotactic radiotherapy (SRS) involves high doses of radiation to small tumour areas, particularly for intracranial conditions (brain cancers) and arteriolar malformations without incisions (Cassidy et al., 2010). Other cancers are spinal, liver, lung, prostate, kidney, and other tumours. Repeated SBRT may occur and sometimes it is fractionated.

Another type of external radiotherapy is electron beam radiation which can be converted to X-ray. It is used to treat skin cancers near the body’s surface. It is given using a linear accelerator but is invisible or felt on the skin. Particle beam radiation therapy is made of energy by protons or neutrons. Radiation released from the machine with high-energy particles travels deep into tissue. It is distinctive from X-rays where they are released at a particular distance to limit the effect on the front and behind the tumour. Particle beams are delivered by particle accelerators called cyclotrons or synchrotrons.

Proton beam radiation therapy is different from X-ray/photon where they travel certain distances similar to particle beam so normal tissues behind and front have minimal radiation. Proton therapy has two respective techniques: two sets of blocking devices shaped to proton beam the target. Pencil beam scanning uses magnets to move or steer the beam. It has shown a disadvantage in treating solid cancers but has been used to treat eye, prostate, spinal, skull, sarcoma, head, neck, and childhood cancer (American Cancer Society, 2025). The key differences between external radiotherapy and proton is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Differences between different forms of external therapy (Alford, 2017)

Surgical Oncology

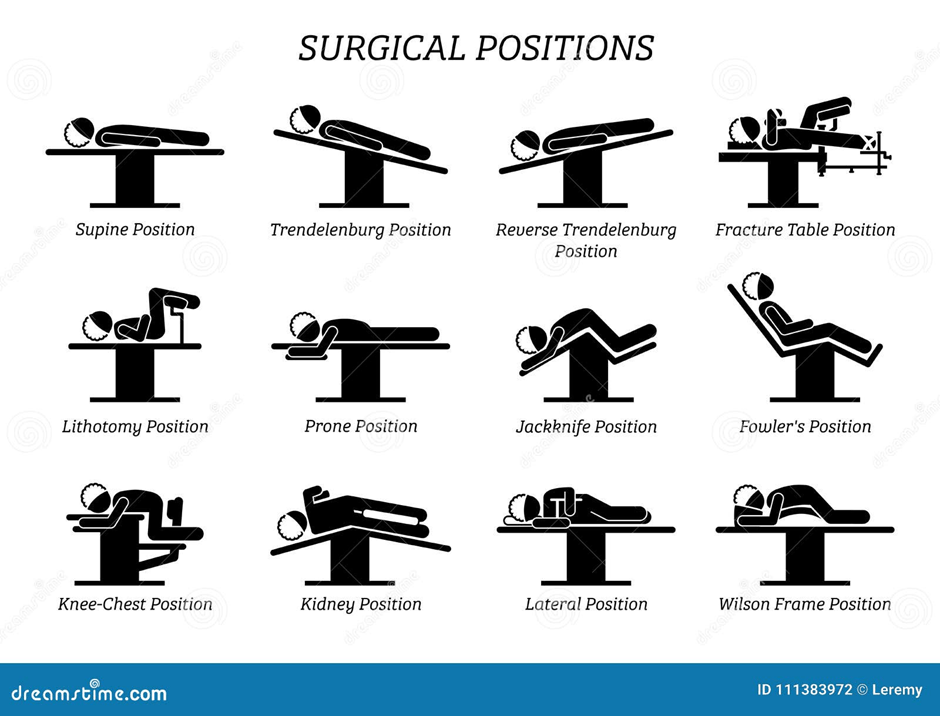

Surgery is the cornerstone for the diagnosis and treatment of localized solid cancers and in some cases, metastatic cancer for long-term survival, for instance, testicular and thyroid cancers. Several factors influence whether surgery should be opted as the primary method of treatment: general health status, type of cancer, stage of cancer, prognosis (course and outcome of patient’s disease), and personal preference interplay in decision-making (John Hopkins University, 2024). The surgical positions vary depending on the surgery performed – please see Figure 11.

Figure 11: Positions for patients scheduled for surgery

There are three main surgical procedures: resection, excision, and reconstruction. Resection refers to the complete removal of the tumour. The surgical margin depends on the dimension of the tumour and how affected the tumour is. This explains why radiological imaging is commonly done preoperatively for evaluation by CT, MRI, PET, and lymph node dissection (Nova Hospital, 2025). This suggests the behaviour of tumour cells is imperative when planning treatment as cancer cells can travel via the blood, lymph, or direct infiltration. Upper gastrointestinal cancers, for instance, head and neck, stomach, oesophagus, and lung cancers metastasize via the lymph.

In cases of lung cancer, the en-bloc technique utilized for nodal dissection. At first, a sentinel node biopsy performed on the lymph node. If there are metastatic cancer cells, a blue dye can identify such cells and block the resection of the regional nodes (Cassidy et al., 2010). The lymph nodes are dissected en bloc with adipose tissue as a lump. It fulfills the requirement for complete resection (Tachimori, 2019).

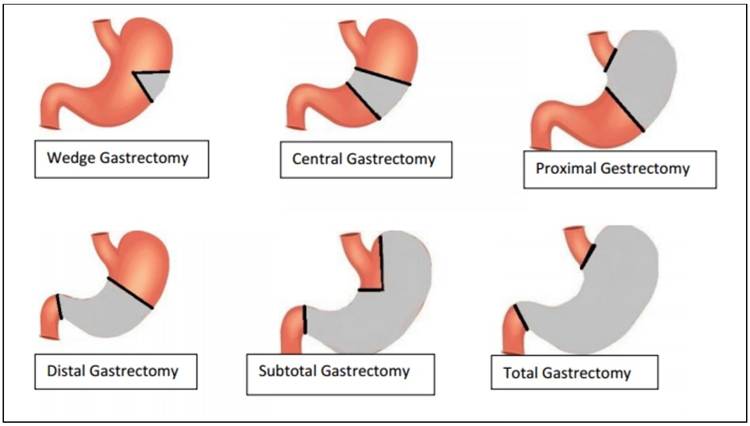

Resection procedures are commonly effective for localized cancers for curative treatment, lowering symptoms, and clearing tumour blockages (Nova Hospital, 2025). Removing a cancer-affected segment occurs in the lung and is called segmentectomy. Removing a larger organ section is referred to as lobectomy and commonly occurs in patients with lung or liver cancer – please see Figure 12. Total resection removes the whole organ, for instance, the stomach (gastrectomy), and colon (colectomy). Some require additional radical steps where adjacent structures and lymph nodes are removed. It commonly occurs in patients with prostate cancer (Nova Hospital, 2025).

A colectomy is performed if there are multiple polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, or intestinal obstruction (Agrawal, 2021). If tissues are unhealthy or there is a prolonged time for wound healing, a temporary procedure involves the intestine being opened and a stent positioned to relieve the obstruction over the abdomen. A stoma bag is attached to the open end of the intestine and as symptoms improve post-chemotherapy, the ends of the intestines reconnect; this is known as ostomy (Agrawal, 2021).

Figure 12: Types of surgery performed on lung cancer. The pink areas are the areas removed by surgery.

In cases of the operable disease, the stomach gives long-term survival with T1N0 and T1N1 tumours. Limited gastric resection for early staged cancers. As seen in Figure 12, there are different types of gastrectomy. Wedge involves a triangle shape around the removed tumour and commonly occurs in the middle of the stomach at the great curvature (left edge) (Canadian Gastric Cancer Association, 2021). Central gastrectomy is where the middle of the stomach is removed. The oesophagogastric junction and proximal stomach (upper stomach) require oesophago-gastrectomy. Distal tumours in the lower stomach near the first segment of the small intestine (duodenum) are removed and are known as partial gastrectomy. Subtotal gastrectomy removes all stomachs apart from the oesophagogastric junction and oesophagus. The total gastrectomy removes all the stomachs and may include the oesophagus and duodenum (Canadian Gastric Cancer Association, 2021; Tamura, Takeno, and Miki, 2011). Monitoring patients for post-operative complications is essential, for instance, inadequate removal of cancers, infections, bleeding, or organ dysfunctional issues (Nova Hospital, 2025).

Figure 12: Different types of gastrectomy (Canadian Gastric Cancer Association, 2021). The grey area highlights the sections removed.

Excision removes a small section of normal tissue for localized cancers, preserves more normal tissue, and, lower complications such as infection, wound healing, and scarring (Nova Hospital, 2025). It is commonly performed for breast, soft tumours, and skin cancers (Nova Hospital, 2025).

In cases of breast cancer, a simple excision involves the direct removal of the tumour. Wide local excision (lumpectomy) is the removal of the tumour and surrounding healthy tissue of breast cancer within good margins to ensure complete excision and conservation of the breast. Radical excision removes lymph nodes and neighbouring tissues for breast cancer (Cassidy et al. 2010). This is because the breast and colon have a dual method of spreading via the blood and lymph.

Mastectomy for large in situ cancers and the mammographic screening of local small non-invasive cancers of the breast can detect the lesion. It is often microcalcified by the radiologist. Another X-ray is performed to ensure complete excision of the abnormality (Cassidy et al., 2010). Another example of total excision involves the mesorectum presented in Figure 13 where the rectum and mesorectal fascia are removed to lower relapse for patients with rectal cancer.

Figure 13: An MRI scan of the rectum

Microsurgery aims to reconnect blood vessels and small areas of tissue that are cut or disrupted during surgery (John Hopkins University, 2025). Mohs Micrographic Surgery for skin cancer is an example and removes tissue until the disease-free margin is reached. A biopsy ensures all tumour cells are removed. Active monitoring for recurrence and wound healing, local anaesthesia for smaller tumours (Nova Hospital, 2025).

Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery for colorectal, renal, and prostate cancers to stage the malignancy (Cassidy et al., 2010). Amongst the advantages are less cutting, less blood loss, short hospital stay, and lower chances of post-operative stress. In cases of colon cancer, laparoscopic or keyhole surgery produces several holes called ports over the abdomen. A camera with high resolution can have a clear view inside and is projected onto a monitor – please see Figure 14. Other ports hold long and thin instruments. Robotic surgery aims to use the 3D camera for depth perception. Arms contain a range of surgical instruments that can rotate to help the surgeon operate – please see Figure 15 (Agrawal, 2023).

Figure 14: An overview of Laparoscopic surgery

Figure 15: Laparoscopic colectomy

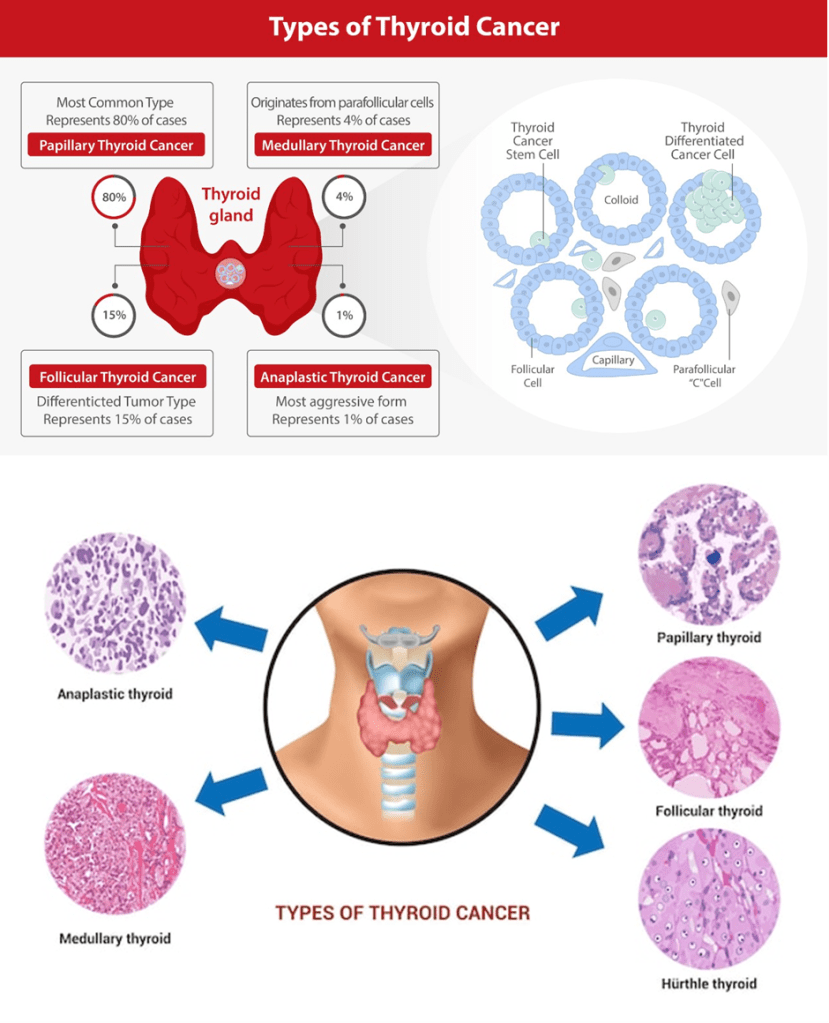

Some types of thyroid cancers vary in their method of metastasis. Papillary thyroid carcinoma via the lymph fluid and follicular thyroid carcinoma travels via the blood. Thyroid cancer affects a particular cell type – please see Figure 16. Unilateral total thyroid lobectomy performed for low-risk patients with identified recurrent laryngeal nerves. Total thyroidectomy may also occur post-radiotherapy if the tumour is multicentric (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Figure 16: Types of thyroid cancer

Reconstructive surgical procedures return the normal function and appearance of maxillofacial and breast cancers to build psychosocial well-being with minimal complications. Tissue expander devices are useful for reconstruction, however, free tissue transfer can build difficult structures, for instance, the tongue. It is commonly done after removing the tumour or healing and requires many stages of surgery. Skin grafts and flaps in surgeries performed on patients with skin, head, and neck cancers. Reconstruction of the breasts after mastectomy using a new implant or naturally by extracting tissue from the back or abdomen. Prosthetics are commonly used for bone sarcoma (John Hopkins University, 2025). Infections may occur and rejection of donor organs may arise despite the prescription of immunosuppressive drugs (Nova Hospital, 2024).

Prophylactic surgery is used for patients with cancers caused by genetic mutations. For example, the mutated BRCA1 gene and HER2 gene can increase the risk of breast cancer. A mutation in the Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene is responsible for the appearance of polyps (abnormal growth of cancer) referred to as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) can cause colon cancer. Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) can cause thyroid cancer (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Another form of surgery is cryosurgery which involves the freezing of normal and cancerous cells. Cryosurgery is performed on patients with skin cancer where liquid nitrogen or argon gas is sprayed or directly onto the skin – please see Figure 17. Patients with cancers such as liver, cervical, localized prostate, bone, eye, and lungs may also undergo cryosurgery. In some cases, a patient is put to sleep, and a thin tube with intense cold is aimed at the tumour site. Side effects may occur in patients with cervical and lung cancer where spotting and haemotypsis (coughing of the blood) occur respectively (John Hopkins University, 2025).

Figure 17: Cryosurgery on the skin.

Laser surgery involves a high beam of light and can be used alone and in combination with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. This surgical technique is commonly performed for cancers of the gastrointestinal (oesophagus, stomach, rectum), gynaecological, and head and neck cancer (John Hopkins University, 2025).

Radiofrequency ablation surgery uses heat from radio waves to destroy cancer cells, particularly in primary and secondary lung and liver cancers.

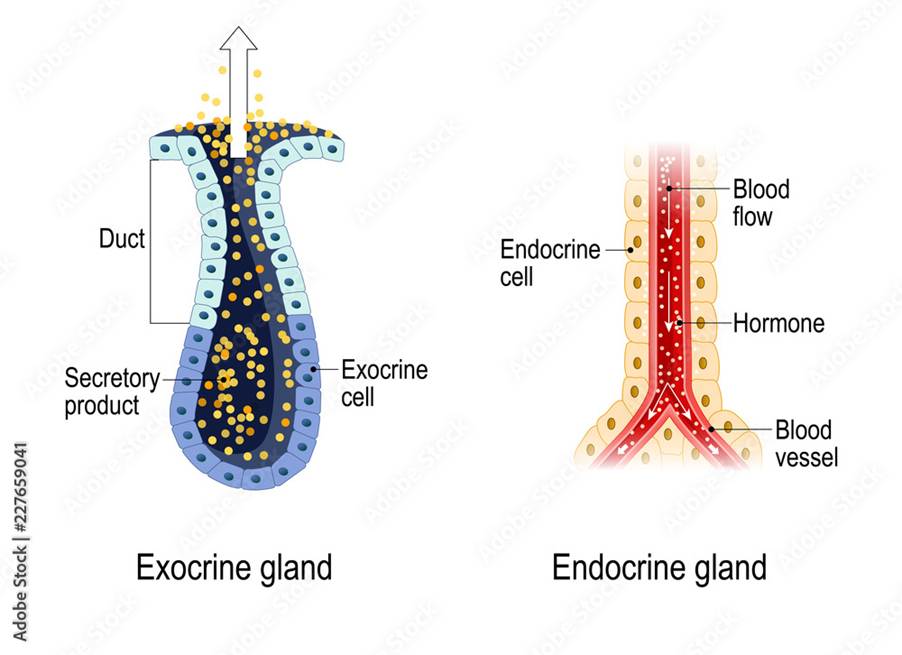

Hormone therapy

There are two types of glands present in the human body: endocrine and exocrine. Endocrine glands secrete natural chemical messengers called hormones that travel through the blood to respond to body changes and maintain the internal environment. For example, growth hormone is secreted in the pituitary gland and helps with growth. Testosterone is secreted in the testis and is responsible for male sexual characteristics and development. Prolactin secreted in the pituitary gland helps with milk production in mammary glands. Insulin, somatostatin, and glucagon secreted in the pancreas regulate glucose levels. Antidiuretic hormone otherwise known as vasopressin is produced in the pituitary gland and regulates the water and ion levels in the body. The other type of gland is the exocrine gland which secretes chemicals in ducts – please see Figure 18. Examples of chemical secretions are oil, mucus, and enzymes.

Figure 18: Types of glands

Certain cancers like breast, ovarian, kidney, thyroid, testicular, and prostate cancer depend on hormones. Oestrogen and progesterone are required for the progression of ovarian and endometrial cancers. Androgens such as testosterone are needed for increased prostate cancer growth. The serum concentrations of oestrogen and testosterone hormones are regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. The site of oestrogen synthesis varies on age: Oestrogen in premenopausal women is produced in the ovaries and in post-menopausal women by the enzyme aromatase that converts androgens produced in the adrenal cortex to form oestrogen. The primary treatment involves castration in breast and prostate cancer (Abraham, Ocen, and Staffurth, 2023). Hormone therapy can stop or block these effects to evade cancer growth and progression.

However, if the patient produces low levels of a hormone because the gland or organ has been resected or removed. Hormone replacement therapy helps to alleviate symptomatic effects. For instance, testosterone helps replace sexual activity (libido) and increase erectile function. It can also lower the risk of overweight and fatigue. Some studies discovered that hormone replacement therapy is not associated with increased mortality rates in patients with breast cancer.

In other studies, the oestrogen receptor protein binds to the hormone (ligand) that elicits tumourigenic potential (Bluming, 2022). Anti-oestrogen therapy in early and advanced breast cancers is stimulated by the oestrogen-positive hormone receptor. The oestrogen receptor is a steroid hormone receptor that can translocate into the nucleus and induce transcription of target genes involved in cell survival and proliferation. It is estimated 70% of breast cancers are sensitive to anti-oestrogen therapy, and multiple drugs alleviate oestrogen (Patel et al., 2023).

One of the main selective oestrogen receptor modulations (SERM) is Tamoxifen alongside aromatase inhibitors can be used as adjuvant therapy after surgery to reduce recurrence. Their mode of action varies with cellular type. In the breast tissue, the SERM drug stops oestrogen from binding to its receptor and represses the transcription of target genes by recruitment and association co-repressors. Specifically, the Phase III trial SERM drug inhibits the activating function (AF) domain in the oestrogen receptor (AF2) but allows AF1 to bind via other signaling pathways. Examples of signaling pathways include PI3K-AKT mTOR, RAS-MAPK, and others. In contrast, the drug can also allow association with coactivators to induce transcription in the bone and endometrium (lining of the uterus) (Patel et al., 2023). Another example is Raloxifene part of a combined trial for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), which prevents breast cancer without increasing the risk of endometrial cancer (Patel et al., 2023).

Aromatase inhibitors block aromatase enzyme which converts androgens to oestrogen; halting oestrogen synthesis. Aromatase inhibitors combined with CDK 4/6 inhibitors like abemaciclib have shown greater efficacy. However, some patients experienced resistance within 6 months of starting oestrogen therapy for metastatic breast cancer or relapse within two years for early breast cancer. Secondary endocrine resistance occurs where relapse while on adjuvant oestrogen therapy after two years or one year of completing adjuvant oestrogen therapy. Causes of drug resistance are linked to oestrogen receptor mutations, loss of receptors, gene amplification, translocation, and dysregulation of key signaling pathways (Patel et al., 2023).

A new generation of anti-oestrogen therapy is designed to overcome the limitations of resistance and other endocrine therapy. Selective oestrogen receptor downregulators/degraders (SERD) stop the oestrogen receptor from entering the nucleus by alterations in the oestrogen receptor structure and halt gene transcription. Fulvestrant has shown efficacy in metastatic breast cancer. A positive efficacy response was also seen in patients with oestrogen receptor one (ESR1) mutations upon treatment with the Phase III clinical drug Giresdestrant (Patel et al., 2023).

Moreover, there are still clinical trial drugs in the early phases being developed in clinical trials for early cancers and metastasis: Complete oestrogen receptor antagonists (CERANS), Selective oestrogen receptor covalent antagonists (SERCA), and proteolysis targeting chimeric proteins PROTAC.

CERANS target the transcriptional activation domain AF1 and AF2 of oestrogen receptor structure by recruiting nucleus receptor corepressor to inactivate AF1 and indirectly inhibit AF2. Normally, AF1 is activated by mTOR/PI3K AND MAPK whilst AF2 is activated by the oestrogen ligand. A key example of a CERAN drug is OP-1250 which is orally bioavailable and shrinks the tumor size in the breast in mutant and wildtype/non-breast cancer patients (Patel et al., 2023).

SERCA covalently binds to the cysteine residue of the oestrogen receptor protein structure to inactivate the oestrogen receptor and prevent transcription. A key example is HRB-6545 which covalently binds to cysteine at position 530 in wildtype and mutant (Patel et al., 2023).

PROTAC has dual ligands: one binds to the target protein (oestrogen receptor) and the other ligand binds to the E3 ubiquitin ligase. This causes ubiquitination and degradation of the target protein via the ubiquitin-proteosome complex (Patel et al., 2023).

The use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) as adjuvant therapy to surgery and radiotherapy has shown a positive therapeutic response in patients with prostate cancer. Decreasing testosterone slows cancer growth (Gomella et al., 2010). Diethylstilbestrol, a semi-synthetic oestrogen compound can be used to treat prostate cancer. However, there was an initial limitation due to cardiovascular complications where there is a risk of embolism (Gomella et al., 2010). Cyproterone acetate is another steroid anti-androgen that blocks androgen receptor interaction and lowers testosterone levels (Gomella et al., 2010). A decrease in testosterone can also be elucidated by inhibiting the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) in the anterior pituitary gland by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists. Degarelix is more direct compared to leuprolide and faster reduction of prostate stimulating antigen (PSA) post-castration (Gomella et al., 2010).

The combination of hormonal therapy and radiotherapy has shown efficacy in patients with prostate cancer (early and late stages). Androgen ablation leaves few cancer cells for radiation therapy to eradicate (Gomella et al., 2010). Hormone therapy also radiosensitizes where androgen ablation before radiotherapy causes a smaller prostate, better blood flow, and less necrosis in regions deemed resistant due to hypoxic conditions (Gomella et al., 2010), A combined approach has several advantages where it limits radiation exposure to adjacent tissues e.g. bladder and rectum. The maximal shrinkage is 3 months for most prostates, some could last up to 6 months with similar outcomes of 31% decreased size of the prostate gland (Gomella et al., 2010).

Biological Therapy

Immuno-oncology has shaped cancer care where biological therapy helps stop cancer cells from dividing and growing by promoting immune cells to apply a cytotoxic killing mechanism on cancer cells. The success rate of biological therapies depends on the type of cancer, clinical outcomes of previous and current therapeutic modalities, and how far it has spread. Targeted therapy such as monoclonal antibodies (MAB) can target specific proteins or cell surface markers known as antigens on cancer cells. Examples of monoclonal antibodies are Trastuzumab (Herceptin) and Cetuximab for breast and colon cancer respectively. Trastuzumab blocks the HER2 receptor whereas, Cetuximab blocks the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Cassidy et al., 2010).

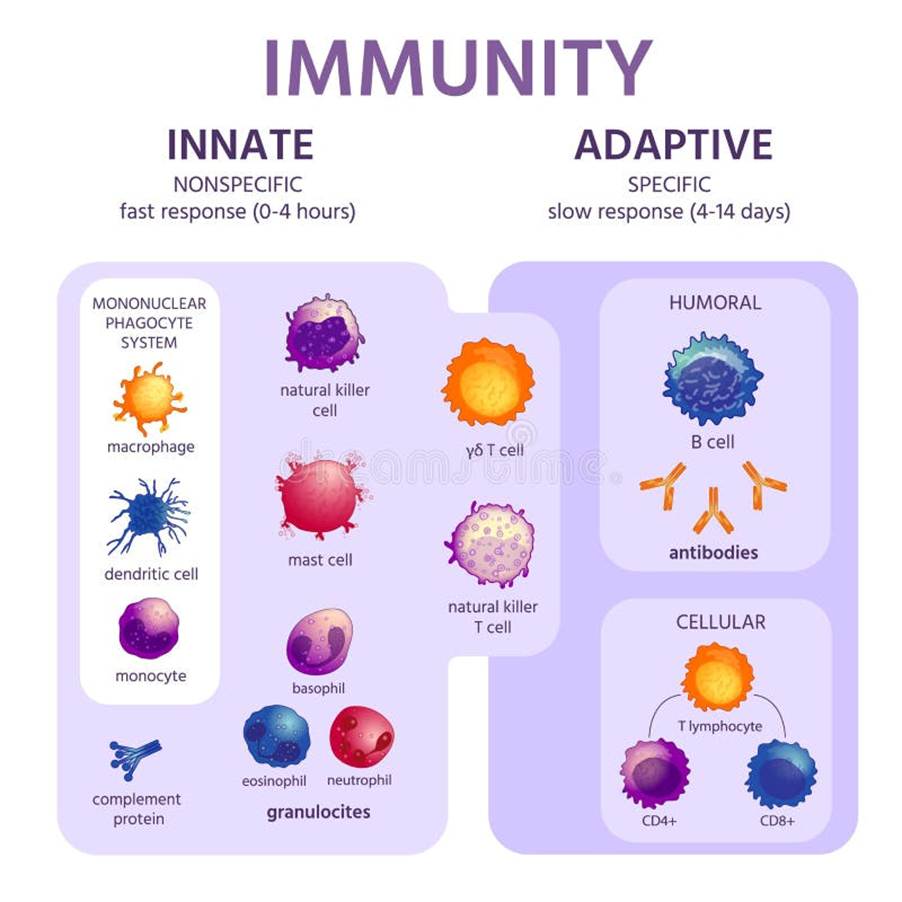

Overview Of The Immune System

The immune system is the body’s way of fighting off disease-causing microorganisms called pathogens. There are two types of immune systems: innate and adaptive (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008). The innate immune system is the pre-existing defense mechanism that helps prevent infection induced by pathogens or forms a defense against it in a non-specific manner. This implies the response is the same regardless of the pathogen (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008).

In contrast, the adaptive immune response has a specific mechanism subdivided into humoral and cell-mediated responses. The humoral response recruits B lymphocytes (B cells), whilst the cell-mediated response involves T lymphocytes (T cells) (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008).

There are many types of immune cells and proteins involved in the immune response – please see Figure 19. Macrophages, mast cells, natural killer cells, and polymorphonuclear granulocytes are part of the innate immune system. However, B cells and different types of T cells: CD8 and CD4 are part of the adaptive immune system. Two cells overlap in innate and adaptive responses: T cells and natural killer cells. Dendritic cells function in both systems.

Figure 19. Types of immune cells found in the innate and adaptive immune response

The Innate Immune Response

The innate response is the first line of defense that comprises physical, chemical, and biochemical barriers (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008). There are five stages involved in the innate response: awareness of the infection, immediate response to the infection, delayed response (if immediate is ineffective), elimination of the pathogen, and provision of immunity. Recent evidence suggests that the innate system can develop a form of memory to prevent the recurrence of infection without T and B lymphocytes and is dependent on the receptor (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2025).

Immune cells related to the innate response have receptors that recognize pathogens based on their characteristics. An example of a receptor is mannose, a C-type lectin carbohydrate-binding protein that recognizes complex carbohydrates. CD-14 is another type of receptor that acts as a co-receptor with TLR4 (toll-like receptor) in detecting bacterial liposaccharides. TLR are a family of receptors that recognize a variety of pathogens (TLR1 – bacterial lipopeptide, TLR2 – peptidoglycan, TLR3 – dsDNA) (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008).

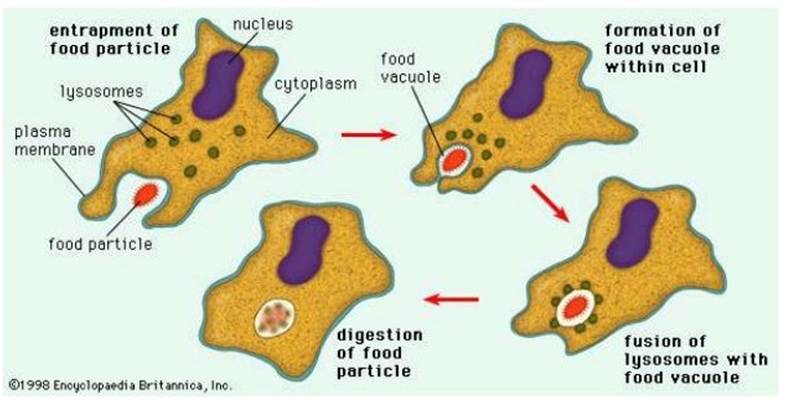

Recognition helps in the elimination of the pathogen or it limits its replication. After recognition, phagocytosis takes place where engulfment and digestion of pathogenic bacteria and other foreign particles occurs. It is conducted by macrophages produced in the bone marrow and found in most major organs and tissues, for instance, non-neural cells such as microglia, spleen, lymph nodes, and liver (Kupffer cells). Macrophages are differentiated from monocytes in response to tissue injury and infection. There are two types of macrophages: fixed and free. Fixed macrophages are positioned in the connective tissue whereas, free macrophages move around between cells and stick together (aggregate) in infectious sites to remove the pathogen. They also help stimulate the differentiation of T-helper sites by acting as antigen-presenting cells (APC) via the antigen on its surface (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024).

Phagocytosis consists of four stages: attachment of the phagocyte to the pathogen, extension of the membranes around the particle, and engulfing the pathogen into the vacuole. The phagocyte then kills and degrades the pathogen using enzymes present in the vacuole – please see Figure 20.

Figure 20: Phagocytosis

Another process that can occur is the secretion of cytokines in response to pathogen stimuli to help support macrophages. They are expressed in M1 macrophages and predominantly found in viral and bacterial infections where they stimulate T helper cells; a type of leukocyte (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). Leukocytes have a unique ability to move around the body, particularly in and out of the blood vessels and tissues. This is controlled by the adhesion molecules and chemotactic agents.

Adhesion molecules bind to each other in a specific manner and enable cells to interact. Amongst the examples of adhesion molecules are glycoproteins and integrins. Glycoproteins are lectins –superbinding molecules expressed on leukocytes or endothelial cells. Integrins are heterodimeric proteins that consist of alpha and Beta chains expressed on the leukocytes (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; Brooker et al., 2008). M2 macrophages function in tissue remodeling and wound healing. It secretes the anti-inflammatory marker interleukin (IL-10) (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024).

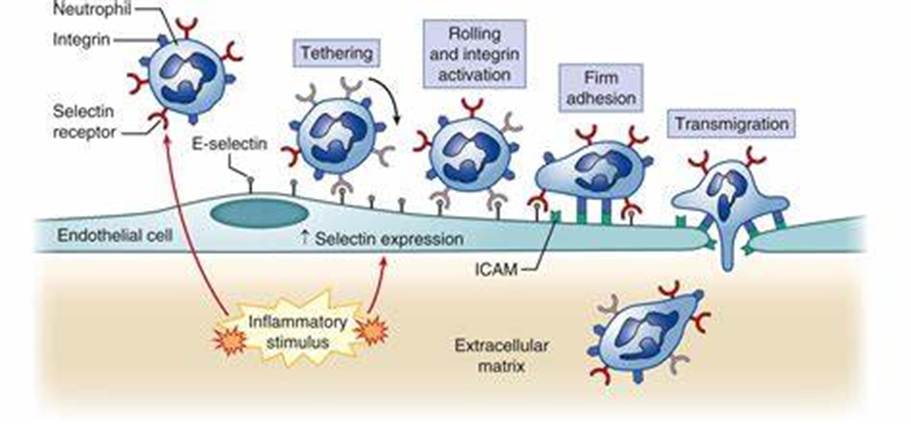

Extravasation is the process of cells leaving the bloodstream, crossing the endothelial layer, and entering the tissue. There are three respective stages to induce acute inflammatory response due to direct tissue injury or systemic stress like hypothermia or hypotension: Recruitment of neutrophils, activation and attachment, and transendothelial migration (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). Neutrophils are one of the main polymorphonuclear granulocytes, characterized by having a lobed nucleus and fine granules in their cytoplasm. These granules turn purple when stained with Romanowsky stains (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007). It has a short half-life of about 8 hours and duration could increase due to inflammatory signals (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). It is produced in the bone marrow in response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Neutrophils are regulated by interleukin (IL)-17 from T-cells and IL-23 from macrophages (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). They normally travel in the center of the bloodstream away from the endothelium.

Neutrophils contain three types of pro-inflammatory granules – azurophilic (primary), specific (secondary), and gelatinase (tertiary) granules. These granules have enzymes called proteases that help with remodeling tissue and wound healing (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). Neutrophils can enter damaged or infected sites and release these granules extracellularly or into the phagosome to help ingest and destroy invading microbes (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). Additional steps are made to support phagocytosis: a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) aims to sequester extracellular pathogens by releasing fiber meshwork to allow the adherence of histones, proteins, and enzymes (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024).

An inflammatory response may occur resulting in vasodilation and the bumping of neutrophils along the endothelium in a rolling motion. Pro-inflammatory mediators such as Interleukin-1 (IL-1β) and tumour necrosis factor, TNF-α facilitate this motion. The endothelial cells are activated to express P-selectins and E-selectins on their surface. These selectins bind to sialyl-Lewisx on the surface of the neutrophil slowing it down and making it roll along and adhere to the endothelium (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007).

The activation and firm attachment involve the binding of LFA-1 integrin on the neutrophil to the ICAM-1 on the endothelium. However, before the LFA-1 can bind, it undergoes conformational change induced by the interleukin (IL-8) produced as part of an inflammatory response in the extracellular matrix of the endothelial lining. IL-8 can bind to IL-8 receptors present on the neutrophil surface. Once conformation has occurred, LFA-1 can firmly bind to ICAM-1 on the endothelium – please see Figure 21. The neutrophil squeezes between the endothelial cells where it contacts the basement membrane and releasese enzymes that digest away the membrane; this allows the leukocytes to enter the tissue.

Figure 21: Inflammatory response (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024).

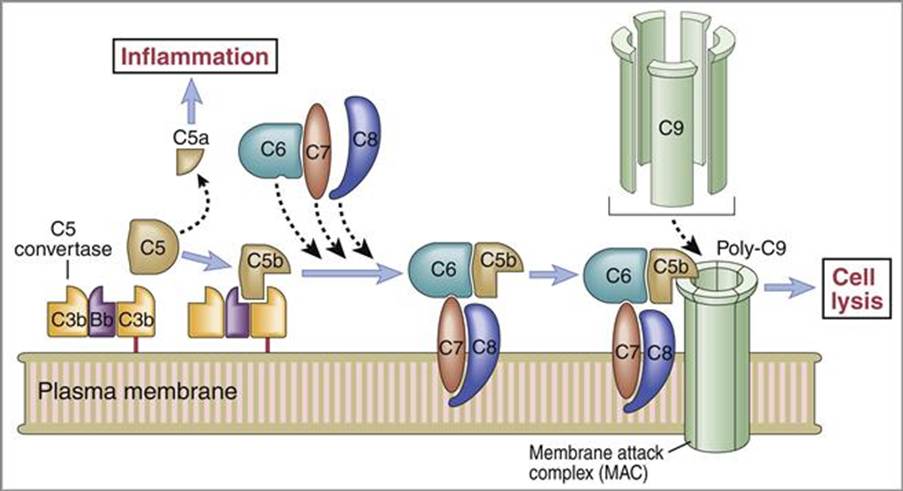

The complement system consists of plasma proteins (C1-C9) that interplay in the resistance mechanisms to infection. Pro-enzymes and other factors activate each other to produce a variety of active proteins. The three complement pathways are classical, lectin, and alternative where they initiate differently but have a common endpoint to form a membrane-attack complex (MAC) – please see Figure 22. The cell-associated C5 convertase cleaves C5 protein to produce C5b. C5b adheres to C5 convertase. C6 and C7 proteins bind sequentially and form a trimolecular and lipophilic complex with C5b into the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane or cell wall. The C8 protein stabilizes the complex. The polymerization of C9 molecules (Poly-C9) around the C5b-C6-C7-C8 complex form MAC. The MAC creates a pore in the membrane that allows ions and small molecules to diffuse, but not proteins due to molecular size. An influx of water enters the cell resulting in cell lysis ‘bursting’. C5a is released when C5 undergoes proteolysis and the inflammatory response is stimulated (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024).

Figure 22 The Complement system (Oncohema Key, 2016)

Under immune surveillance, the innate cells can eradicate nascent cancer cells and T-cell immune checkpoints, particularly CTLA-4 and PD-1 to increase autoimmunity (Esfahani et al., 2020). Cancer immune-editing protects the host against the tumour environment via immunogenicity (Fan et al., 2023). This presents the several methods the immune system can recognize mutated oncogenic genes or suppress the immune response to stop cancer growth and proliferation.

The Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive immune system is divided into humoral and cell-mediated responses. Among the similarities of the pathways are clonal expansion and robust memory. However, the effector cells are distinctive. The humoral response is mediated by B lymphocytes (B cells), whereas the cell-mediated response involves T lymphocytes (T cells) (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

B cells are derived from the bone marrow and circulate through the bloodstream, spleen, and lymph nodes. B cells produce antibodies otherwise known as immunoglobulins with high specificity to B cells. Antibodies can be in two forms: excreted (IgG, IgA) or expressed on the cell surface of the B cell (IgM, IgD). Soluble IgM is produced during the early stages of infection before transitioning to form primarily IgG, IgA, and IgE antibodies during the infection. This elevates the affinity for the antigen present on the pathogen due to the genetic rearrangements within the structure of the immunoglobulins (Sabiston Textbook Of Surgery, 2024). B cells also have receptors on the surface that form signaling complexes with the antibody. The receptor is composed of two proteins: Igα and Igβ- antigens bind to Ig – Igα & Igβ to initiate intracellular signaling events to activate B cells (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006).

T cells are produced in the thymus however, precursor T cells are initially made in the bone marrow before migrating to the thymus located in the mediastinum where they are matured and travel around the body. There are two types of T cells and are distinguishable based on the molecules presented on the cell surface. Helper T cells express a molecule called CD4 on their cell surface and are called CD4 T cells (T helper cells). The other type of T cells express a molecule called CD8 on their cell surface, therefore known as CD8 T cells; they become cytotoxic after activation (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

CD4 and CD8 T cells use a receptor called T cell Receptor (TcR) to recognize antigens. The TcR is different from the antibody and the genes that code for it are found on different chromosomes. The structure of TcR consists of two glycoprotein chains called α and β. Both chains have a similar structure to Ig, as the TcR has a variable and constant domain. TcR is always present on the surface of the T cells (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

Different T cells will recognize different antigens as each TcR will have different variable regions. T cells recognize antigens associated with molecules on the surface of cells called ‘major histocompatibility complex’ (MHC). MHC refers to a region of the DNA on chromosome 6 in humans. All vertebrate species have an MHC with unique names. In humans, the MHC is called HLA (human leukocyte antigen). MHCs are divided into three classes: I, II, and III. The CD4 and CD8 T cells bind to the non-polymorphic region of the MHC to strengthen the bonds (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006).

Once infected the first response will be dealt with B cells (primary response). All B cells differ depending on the Ig variable region of the antibody. The antibody of the cell forms a complex with the antigen of the pathogen or foreign particle. Once activated, the B cell will undergo clonal selection to create the specific antibody. It will proliferate and differentiate into plasma B cells (effector cells) and B memory cells. The effector cells are involved in phagocytosis. The B memory cells remain in the body and activate during the secondary response, if the same pathogen were to infect again (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

Once the B cell has ingested the pathogen it will go through antigen processing and presentation. Endogenous antigens are produced within the cell (viral proteins) and are processed and presented by Class I MHC. Exogenous antigens derive from outside the cell and are processed and expressed by Class II MHC molecules (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

All nucleated cells express class I MHC. Proteins are fragmented in the cytosol by proteosomes. The fragments are then transported across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum by transporter proteins. Synthesis and assembly of class I heavy chain and beta2 microglobulin occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and are transported to the cell surface (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006)

A limited group of cells expresses class II MHC, which includes the antigen-presenting cells (APC). The principal APCs are macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells. The exogenous proteins are taken in by endocytosis are fragmented by proteases in an endosome. The alpha and beta chains of MHC class II are synthesized and assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum. This is transported through the Golgi Apparatus to an endosome where the peptide fragments from the exogenous protein are transported to the cell surface.

Infected cells present foreign antigens to CD8 T cells. The MHC Class I (antigen) is recognized by TcR (CD8 T cell). This activates the CD8 T cell; it then proliferates and differentiates into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). The CTL produces cytoplasmic granules containing enzymes (granzymes) and perforin. The CTL releases perforin that makes holes in the plasma membrane of the target cell, the granzymes enter the target cell (via perforin pores) and trigger apoptosis of the target cell.

CD 4 T cells specialize in antigen-presenting cells (APC) present antigen to CD4 T cell. The MHC Class II (antigen) is recognized by TCR (CD4 cell) but this does not activate the CD4 T cell yet. Another signal is required which is the interaction of CD80/CD86 on APC with CD28 on T cells.

Once activated the CD4 T cells synthesize and secrete cytokine (interleukin 2 (IL2) and express receptors for IL2. The IL2 causes proliferation of activated CD4 T cells and differentiation of CD4 T cells into T helper cells; Th 1 or Th2. Th1 helps macrophages and B cells. IL-12 also promotes the differentiation of Th1 cells (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024). Moreover, Th1 secrete interferon-gamma (IFNγ), IFNγ activates macrophages that increase expression of MHCII and increase antigen presentation to CD4 T cells activating more CD4 T cells. Th1 also drives the activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024). The overall effect of this will be the amplification of the immune response against intracellular pathogens.

Th2 helps B cells and IL-4 promotes the differentiation of Th2 cells (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024). The Th2 cells remove extracellular pathogens and induce allergic responses by producing IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024). Th17 is found in autoimmune disorders where IL-17 is stimulated as part of a chronic inflammatory response. IL-6 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) promote differentiation of Th17 cells. This highlights the role of cytokines in T-cell activation.

Regulatory T cells (T-reg) are a form of CD4+ T helper cells essential to develop memory and produce anti-inflammatory cytokines primarily IL-10 and TGF-β (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024). In the realm of surgical oncology, T reg cells increased post-surgery in patients with invasive breast cancer in 72 hours and is compared to large tumour size and high levels of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2). This highlights how suppressing the immune system increases the risk of micrometastasis because circulating tumours cells are destructed. Other events in how T cell inflammatory response is dampened when there is hypothermia, surgical stress and hyperglycaemia, general anaesthesia, and blood transfusion which is presented by the increase of hormones: glucocorticoids and adrenocorticotropic hormones (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024).

Furthermore, dendritic cells are involved in innate and adaptive immune response as the main antigen-presenting cell (APC) and have several functions. In the innate response, Dendritic cells can engulf and degrade antigenic proteins that bind to MHC I and II which are transported to the cell surface of dendritic cells. The dendritic cells are transported to lymph nodes and spleen; lymphoid organs. T cells are then able to differentiate into CD8+ and CD4+ cells. CD4+ cells are activated by extracellular proteins in the lysosome of the dendritic cells and MHC class II molecule. CD8+ cells are activated by intracellular proteins in the cytosol that are processed by the proteasome. Some subtypes of dendritic cells allow the presentation of CD8+ by MHC I (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024).

In the adaptive immune response, dendritic cells stimulate the activity of T cells in some ways: secretion of proinflammatory cytokines e.g. IL-12, IL-8, and IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α,) and surface ligands, e.g. CD80 and CD86 to trigger an immune response (Kciuk et al., 2023). This increases its efficiency than the other APC: B cells and macrophages. Tumour cells can evade the immune system by inhibiting dendritic cells. However, dendritic cells partake in a double-sword mechanism where it can induce immune response towards foreign pathogens and also have a tolerant approach towards the self-antigens and nonpathogen antigens it processes. These antigens stimulate the immunosuppressive T-reg cells (Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 2024).

Furthermore, macrophages, immature dendritic cells, and T cells express the transmembrane receptor CD91 otherwise known as LRP1 that can detect cancer cells undergoing apoptosis by the presence of calreticulin (CRT) and phosphatidylserine on the cell surface of the tumour (Kciuk et al., 2023). Macrophages can then ingest and remove the cancer cells. The high-mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1)—a ligand for toll-like receptor (TLR-4) is released by cancer cells and is needed for activation of dendritic cells and active APC (Kciuk et al. 2023). The dendritic cells uptake the antigens and present them to CD8+ cells with the support of CD4+ cells. (Kciuk et al., 2023).

Figure 23: Innate and adaptive immune response against microsporidia (Creative Commons, 2025)

Cancer vaccines

Viral diseases can be treated by vaccines and anti-viral drugs. Vaccine is a preparation of bacterial or viral antigens induced into the immune system. Early efforts in manufacturing therapeutic cancer vaccines are limited due to the evasion of the immune cells, efficacy, and the role of tumour-associated antigens. The introduction of immunotherapy, MRNA techniques, and tumour antigens facilitate cancer vaccine design and development particularly the role of de novo T cell response target tumour-specific antigens and tumour associated antigens (Marchal, 2025; Fan et al., 2024).

There are different types of vaccines: killed, inactivated, dead or alive bacteria. Killed vaccines contain viruses that were heated or chemically treated to remove their virulence or infectious ability. However, they cannot stimulate the cell-mediated immune system and have good antibody responses (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007). Attenuated viruses are alive and can cause infection but not disease by being adapted to other species and grow poorly in human cells lowering virulence factors. It can stimulate cell-mediated response and antibodies (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007). Subunit vaccines consist of a polysaccharide extracted from bacteria to prevent phagocytosis by activating antibodies for immunity. Purified subunits such as influenza can produce new strains via antigenic drift. Cloned vaccines are cloned viruses or bacteria based on surface antigens projected onto yeast cells to be recognized by the immune system.

There are several characteristics of an effective vaccine: safe, minimal side effects, and can evoke innate and adaptive immune response via herd immunity for long-term protection. Immunization programmes are held by herd immunity where most of the population are immune against an infection. This prevents the specific bacteria or virus from finding an individual who is not immune. Key examples are smallpox, measles and cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV), Hepatitis B (HBV), and Hepatitis C (HBC) (National Cancer Institute 2021; Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006). HBV and HBC can cause liver cancer whereas HPV causes cervical cancer ( National Cancer Institute, 2021; Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

Preventative vaccines for cervical cancer are available, for instance, Gardasil. However, recent research discovered that HPV-16 RNA-lipid complex vaccine, GX-188E with pembrolizumab forms a specific T-cell response in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer (Fan et al., 2023).

The HPV vaccine is a killed or inactive form of viral vaccine where it is commonly treated with formalin. Recent reports declared the introduction of HPV vaccination to both sexes helped decrease 90% of infections induced by high-risk types 16 and 18 involved in cervical cancer. No cases of infection were found amongst those aged 12 to 13 years (World Health Organisation, 2025b). Other viruses that are attributed to HPV are vulva, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal (head and neck cancer).

A well-designed and implemented vaccination program is a key element, however, it is important to understand and appreciate the limitations. No vaccination program can fully prevent disease. Vaccines do not prevent infection rather they prime the immune system to provide a rapid and effective response following infection. This limits the multiplication and spread of the infectious agent and lessens tissue damage. This lowers the severity of the disease and transmission to other people (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

Anti-viral drugs

Anti-viral drugs can prevent infection as vaccines cannot work on rapidly genetically mutating viruses such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). HIV does not directly cause cancer but increases risk by weakening the immune system and providing a modest and therapeutic effect. Anti-viral drugs identify target viral proteins that are disabled and are common across many strains of a virus for broad effectiveness. High throughput screening allows multiple genetic, biochemical, and pharmacological tests within a short period to identify active compounds and antibodies that dysregulate the pathway.

Moreover, there are several limitations when designing an antiviral drug. The signs and symptoms experienced by the patient in acute infections signify the peak of viral replication and there are minimal therapeutic effects (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006). Viral multiplication is tied so intimately to certain cellular processes that most antivirals cannot discriminate between them.

However, viruses do have unique features, so specific antiviral drugs should be able to serve as effective chemotherapeutic agents. An antiviral would be effective if it inhibited any stage of virus multiplication: attachment, replication, transcription, assembly, or release of progeny virus particles.

Recent developments discovered that antigen-specific immune reactions are useful in cancer treatment where shared antigens and personalized neoantigens are incorporated that provoke immune responses based on expression. Shared antigens are public antigens with hotspot mutations in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and target tumour-associated antigens and tumour-specific antigens. Tumor-associated antigens are autoantigens overexpressed in testicular cancer. Tumour-specific antigens are produced by somatic mutations (body cells) to increase MHC presentation or alter recognition of TCR (Fan et al., 2023). After immunization, cancer antigen is absorbed into the APC and processed into the MHC I/II complex stimulating its activation. The activated APC undergoes migration into lymph nodes. MHC I/II binds with T cells to form a complex. T cells migrate and infiltrate the tumour supported by chemokines and cytokines to kill cancer cells (Fan et al., 2023).

One of the main examples of a tumour-associated antigen is melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) normally expressed in the testicles and overexpressed in skin cancer (melanoma). Another example is the overexpression of E6 and E7 proteins in cervical and oropharyngeal cancers (Fan et al., 2023). Shared tumour-associated antigens and tumour-specific antigens are useful targets for immunotherapy whereas the latter is due to not being associated with germ-line nor causing immune tolerance.

Monoclonal antibodies

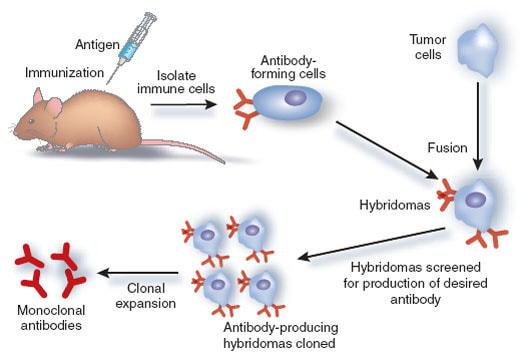

Monoclonal antibodies are artificially produced from a cell clone and consist of one type of immunoglobulin – please see Figure 24. They are formed by combining B lymphocytes (antibody-producing cells) from mouse spleen with mouse myeloma cells to form hybridomas. The hybrid cells rapidly grow and produce antibodies equivalent to the parent cell. They play a fundamental role in diagnosing and treating cancers and can also be in conjunction with radiotherapy, where yttrium-90 applies a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on cancer cells.

Figure 24: The production of monoclonal antibodies (Creative Commons, 2025)

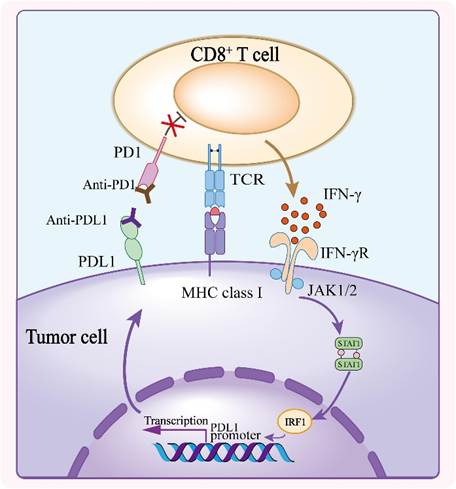

A key target of monoclonal antibodies is PD-1/PD-L1 (programmed death ligand-1) for several cancers. There are three licensed anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab. There are also three anti-PDL-1 antibodies: avelimab, durvalumab, and ateszolizumab (Kciuk et al., 2023). As part of the DNA damage response (DDR), there is an increased expression of PD-L1 expressed on cancer cells to avoid apoptosis. It would be a useful target for combined therapy to restore the tumour microenvironment (Kcik et al., 2024). This is observed in patients with metastatic melanoma who were given CTL1-4 to increase survival (Kciuk et al., 2023).