Original author: Ahmed Saeed

Original published date: 3rd April 2014

Updated by: Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas

Update date: May 2025

Review date: May 2027

Ahmed Saeed is Farah’s brother and is one of the team members of One Ummah Charity. He also tutors Quran and Maths to children.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death, and among the preventative methods of cancer is dietary intake that holds promise to lower the risk of obesity and cancer incidence, mortality, and morbidity rates (Ericsson et al., 2023). Other modifiable risk factors include exercise and a sleep routine.

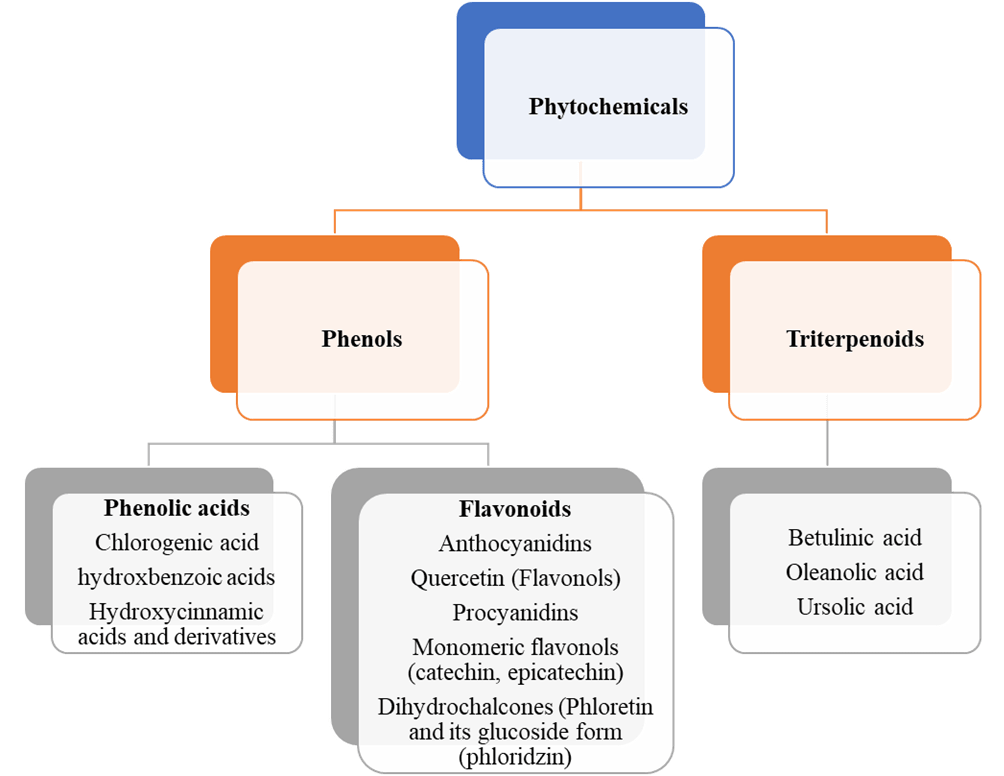

In recent years, the holistic approach of treating cancer using natural products with conventional treatment modalities has been explored. It has shown increasing importance and is essential for the integrated personalised medical approach in cancer care. The anticancer properties exhibited by fruits, vegetables, herbs, spices, and nuts are associated with the type of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), fibre, and secondary metabolic compounds called phytochemicals (Collignon et al., 2023) – please see Figure 1. The classification of phytochemicals is divided into two major groups: flavonoids and phenolic compounds.

It is advised to contact a healthcare professional for the pharmacological effects of natural remedies such as herbs, where plant extracts may influence other medications or treatments (Modglin, 2023). Variation in regulation may also interplay. Promising studies discovered the anti-inflammatory and anti-tumour properties, particularly curcumin, found in turmeric and ginger. Other examples are cayenne pepper and garlic, which can lower the growth of tumour cells and protect normal proliferating cells from the side effects of chemotherapy. Echinacea and ginseng elevate the immune system to lower the inflammation.

Nevertheless, despite the various medicinal values, herbal medicine cannot replace conventional cancer treatments (Modglin, 2023). Additional lack of scientific evidence suggests herbs cannot be reliably considered as a treatment for cancer (Cancer Research UK, 2022). Therefore, the scope of this article aims to focus on several fruits and natural honey that can evade carcinogenesis and progression.

Figure 1 Classification of phytochemicals

Phytochemicals are composed of two main groups: flavonoids and phenolic acids. Flavonoids have several subclasses: anthocyanidins, flavonols, procyanidins, monomeric flavonols, and dihydrochalcones. There are three subclasses of phenolic acids: chlorogenic, hydroxbenzoic acids, and hydroxycinnamic acids. Triterpenoids also have three subclasses: betulinic, ursolic acid, and oleanolic acid. The composition of each bioactive compound varies, whether it is in the seed, flesh/pulp, or on the skin. The medicinal applications of its use also vary and depend on four factors: absorption, metabolism, and bioavailability. Bioavailability is the fraction that is absorbed and available to exert its biological effects, and is affected by the conditions, structure, free or conjugated form, enzyme activity, and pH. Most of the phenolic compounds are initially absorbed in the small intestine before the continuity of the absorption takes place in the large intestine, where the gut microbiota transforms the phenolic compounds into metabolites to increase the absorption rate (Nezbedova et al., 2021).

Grapes

A grape is a perennial and deciduous woody vine found almost everywhere around the world – Please see Figure 2. Its berries can be consumed raw or made into sweets due to their delicious taste: juice, jam, health drink jelly, and even raisins. It can be added to salad or frozen as a refreshment (Center for Healing, 2023). The phytochemical constituents in grapes, resveratrol, quercetin, and catechins are implicated in various cancers, where they inhibit growth and increase apoptosis (cancer cell death) (American Institute for Cancer Research, 2021). Both resveratrol and quercetin are antioxidants that have shown anti-inflammatory responses by preventing DNA mutations and damage, evading cancer cell growth, and decreasing oxidative stress.

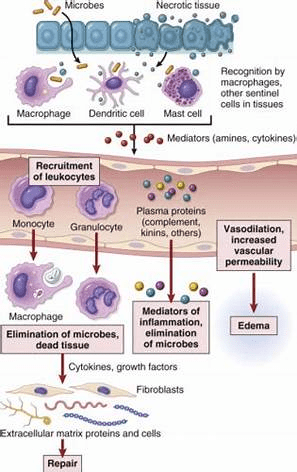

The inflammatory response stimulates the recruitment of immune cells, notably mast cells and white blood cells, to the damaged site, where a high demand for oxygen uptake is required – Please see Figure 3. This causes ROS accumulation that further increases the damage. The intensification of the inflammatory response is mastered by cytokines, chemokines, and metabolites of arachidonic acids and COX-2 that shift the cell to a malignant phenotype (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas, and Sikalidis, 2016). A congregation of signalling agents in the microenvironment of the damaged location perpetuates the cellular stress, sustaining the damage to a chronic state, particularly chemokines interleukin IL-8 and chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha). Polyphenols modify the cancer microenvironment and suppress inflammation, rendering it to higher cytotoxic levels and apoptosis.

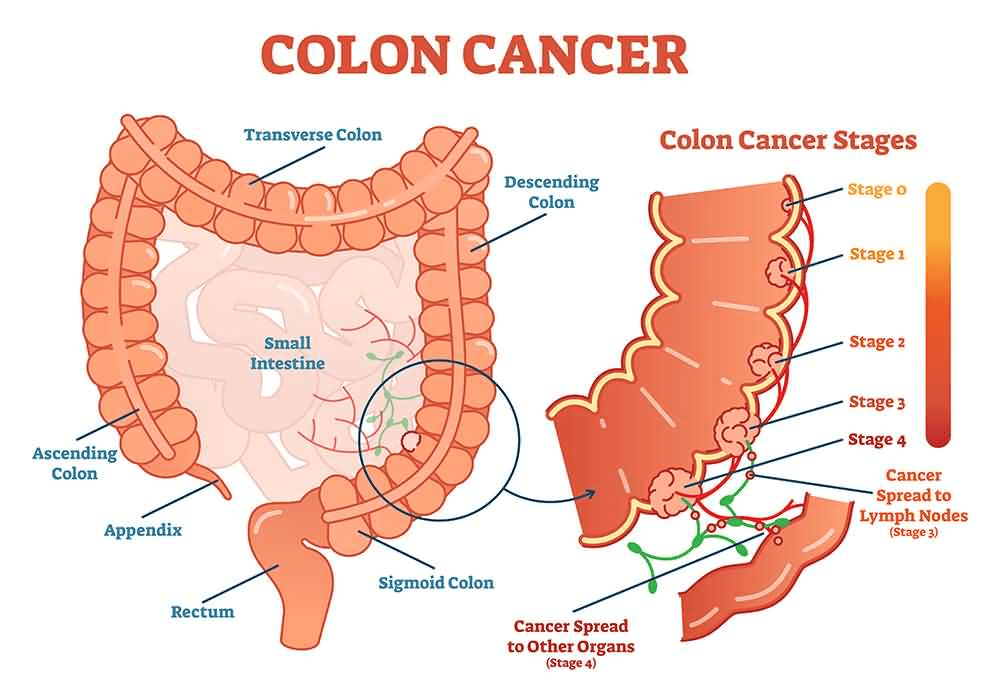

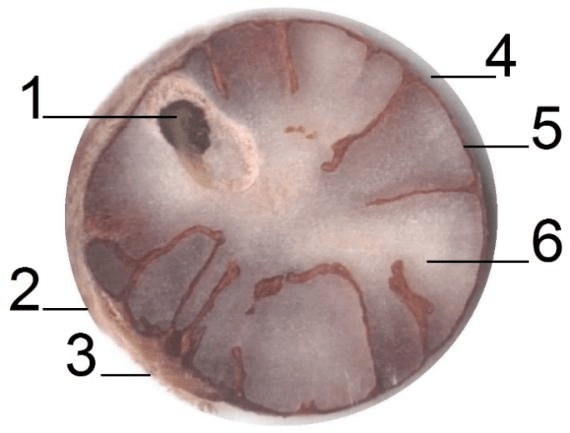

Grape seeds are found in the centre of grapes and are illustrated in Figure 4. An in vivo study using rodent models has shed light on the positive use of grape seed extract in lowering growth of colon and prostate cancer cells (Cancer Center for Healing, 2023). This may be attributed to quercetin where previous studies revealed its anti-tumour properties in patients with prostate and lung cancer (Cancer Center for Healing, 2023).

Dragon Fruit

This pink-skinned fruit pictured in Figure 5 is highly concentrated with phytoalbumin antioxidants. Amongst its chemical composition is lycopene, which holds a dual effect in contributing to the rich colour and has a chemopreventative role in cancers of the skin, lung, breast, prostate, and liver (National Federation For Cancer Research, 2021). Other beneficial dietary compounds are carbohydrate fibers, minerals (calcium, phosphorus), and water-soluble vitamins (C and B2). In turn, this increases the output of metal toxins from the body.

Dragon fruit (pitaya) is derived from the cactus species in the genus Hylocereus and Stenocereus (Dasaemamoh, Youravonf, and Wichienchor, 2016). Hylocereus has three main types that vary in colour: Hylocereus polyrhizus consists of red pulp with red-magenta skin, whereas Hylocereus undatus has a similar skin colour but has white pulp. Hylocereus megalanthus has white flesh with yellow skin (Ariffin et al., 2008; National Federation for Cancer Research, 2021). Please see Figure 5B.

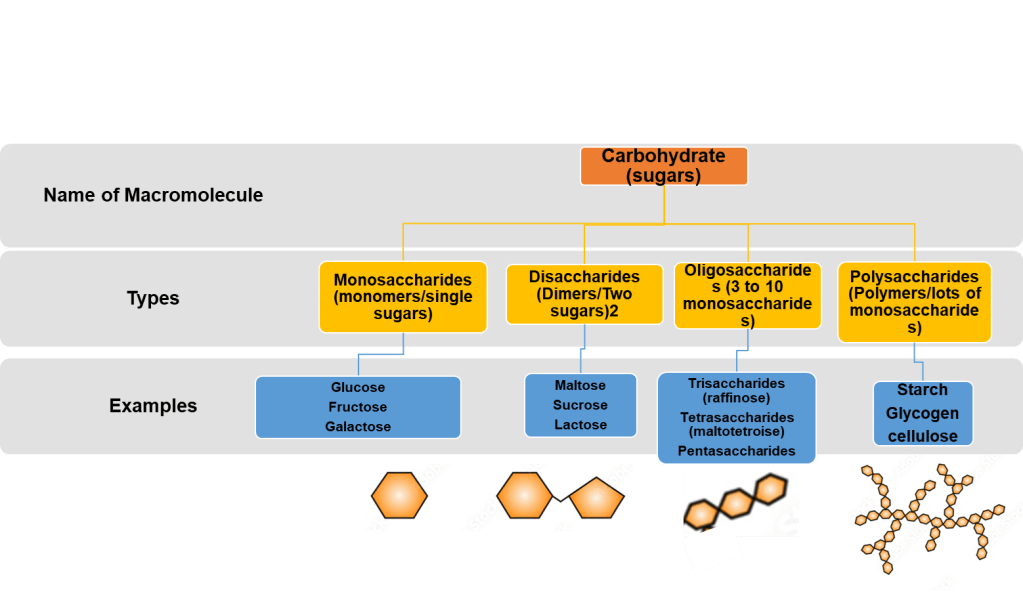

From the flesh of the dragon fruit, non-digestible oligosaccharides (sugars) are resistant to hydrolysis or breakdown by the amylase enzyme and, therefore, can be extracted and fermented (Dasaemamoh, Youravonf, and Wichienchor, 2016); please see Figure 6. Experimental studies discovered that the cell-free broth after fermentation for 24 hours contained various chemical compounds. One of these compounds discovered is butyrate, which inhibited tumour cell growth and proliferation by evading DNA methylation. This is consistent with previous studies that reported a concentration between 1 – 5 mM without affecting non-cancerous cells in the intestinal area (Dasaemamoh, Youravonf, and Wichienchor, 2016; Archer et al., 1998).

Citrus Fruits

Exemplary types of citrus fruits are oranges, lemons, and grapefruits – please see Figure 7. It contains many bioflavonoids, which can enhance the activity of certain enzymes in the human skin, lung, stomach, and liver that alter the fat-soluble carcinogens into water-soluble. This helps to make it easy to be absorbed and expelled from the body. At the same time, the flavonoids can enhance the absorptive capacity of vitamin C in the human body. This vitamin can boost the immune system and prevent the formation of nitrosamines, a strong carcinogen implicated in gastrointestinal cancers. Other biological effects of flavonoids include antiproliferation and key roles in cell communication, regulation, and preventing angiogenesis, where cancer cells can gain a nutrient supply via blood vessels – please see Figure 8 (Cuttler et al., 2008).

A study published in the Journal of Nutrition and Cancer, discovered that people consume high levels of flavonoids and proanthocyanidins, a subgroup of flavonoids. This significantly lowered the development of cancers: 44 percent less likely to develop oral cancer, 40 percent less likely to develop laryngeal cancer, and 30 percent less likely to develop colon cancer compared to other types of cancer. However, the protective effects of flavonoids has statistically shown no significance in patients with bladder and breast cancer (Neuhouser, 2004).

Avocado

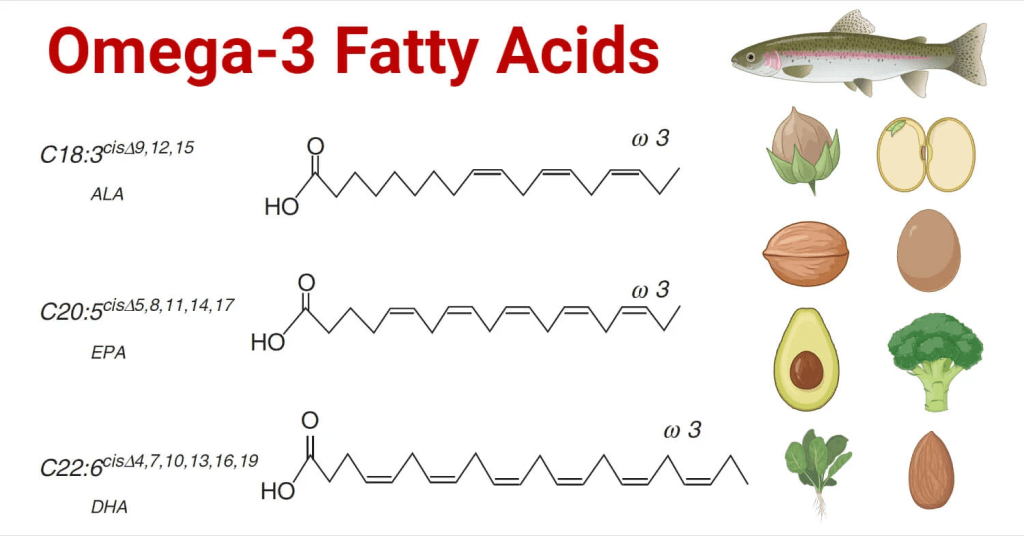

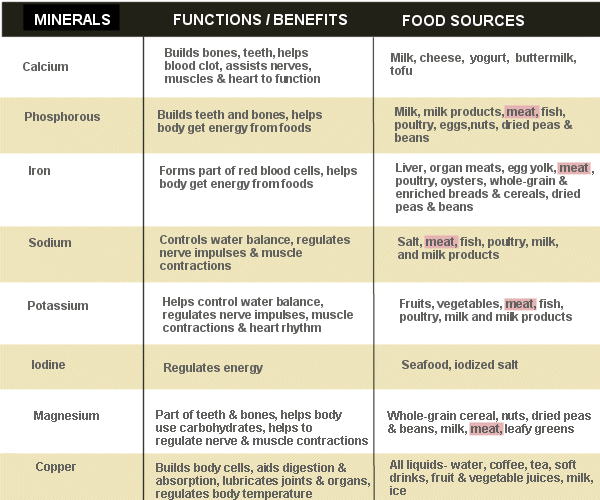

Avocado (Persea Americana) is a green, rich, creamy fruit with a dark green/black leathery outer layered skin. Analogically, this may explain why it is referred to as alligator pear – please see Figure 12. It originates in Central and South America for thousands of years. Avocados uphold a strong nutritional content, namely proteins, fiber, fats, and low sugar (AlKhalaf et al., 2019). The presence of omega-3 fatty acids lowers cholesterol and improves the circulatory system – Figure 14. It contains water-soluble vitamins (B5) and fat-soluble vitamins (E and K) to maintain body regulation. Other reports discovered additional vitamins (C, B1, B2, B6, and B9) and essential minerals are also found, particularly, potassium, sodium, magnesium, iron, and zinc (AlKhalaf et al., 2019; Oluwole et al., 2013). It is estimated that half an avocado a day contains 6.7 g of monounsaturated fatty acids, 345 mg of potassium, 1.3 mg of Vitamin E, and 4.6 g of dietary fiber (Dreher and Davenport, 2013; Ericsson et al., 2023). Some of the functions of vitamins and minerals are presented in Figure 15 and 16 respectively.

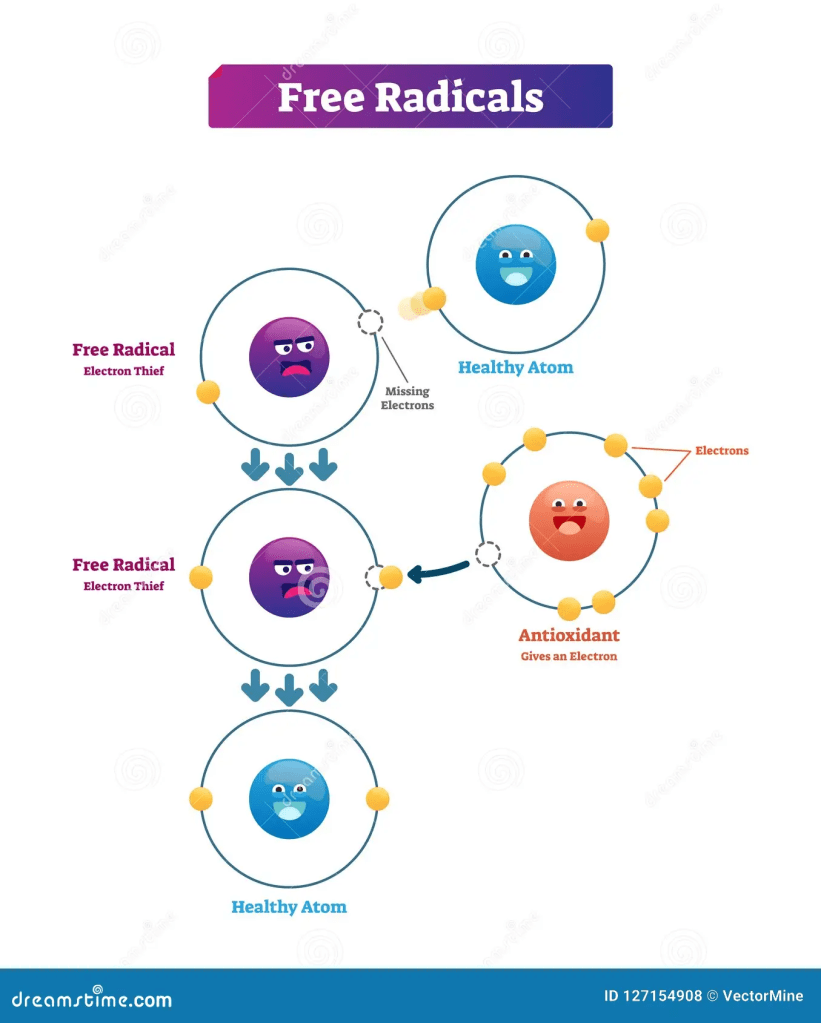

The abundance of phytochemicals in avocados exhibits both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in prostate, skin, and mouth cancer, leading to cell cycle arrest and cancer cell death (D’Ambrosio et al., 2011). Antioxidants helps to neutralise and kill cancer cells – Please see Figure 17. Profounding evidence in in vitro and in vivo experimental studies presented low viability and proliferation of cancer cells, whereas in vivo studies revealed a reduction in the tumour size, volume, and number (Ericsson et al. 2023).

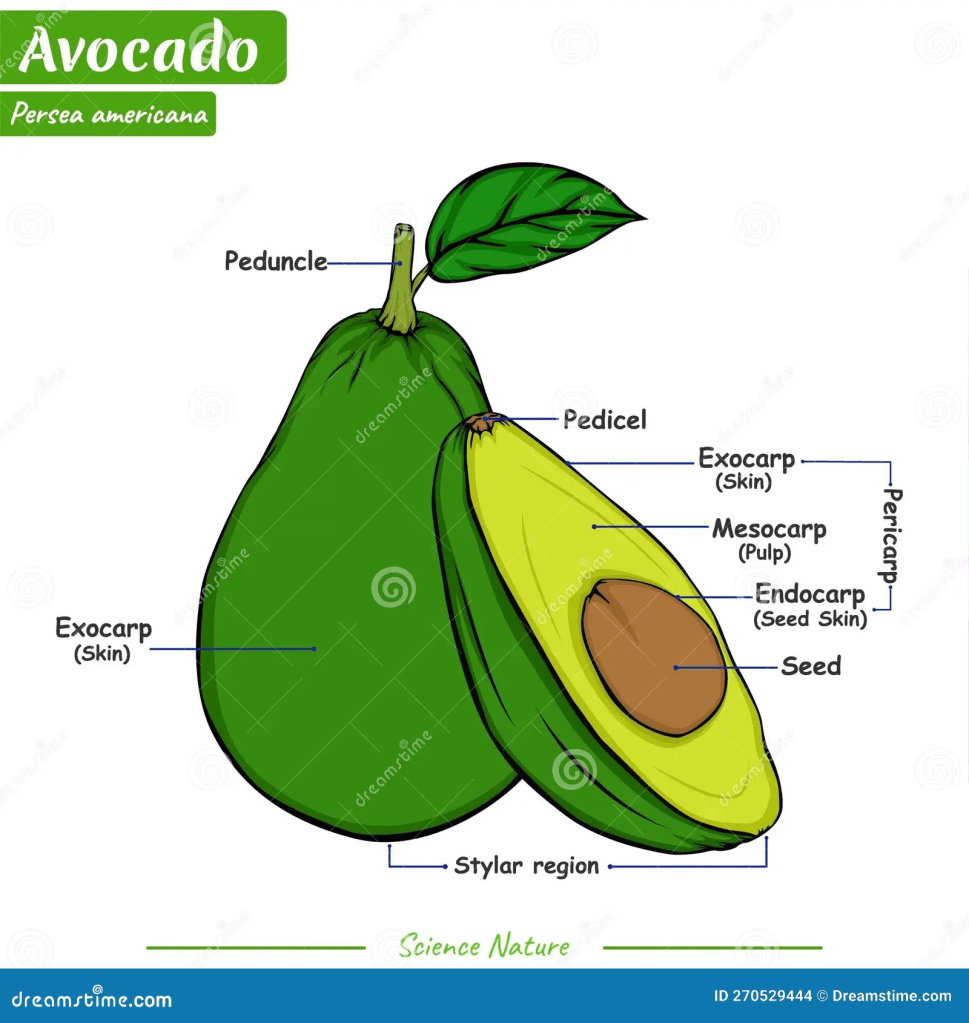

The dark-green area (pith) is heavily concentrated with oxygenated carotenoids, lycopene, and beta-carotene. The structure of the avocado is presented in Figure 18. They exert their antioxidant effects and decrease cellular damage, preventing cancer (AlKhalaf et al., 2019). Lu et al. (2010) discovered that carotenoids play a big role in preventing cancer. Lutein accounts for 70% of carotenoids found in avocado. Vitamin E, also present in avocados, can prevent the growth of androgen-dependent (LNCaP) and androgen-independent (PC-3) prostate cancer cell lines. It leads cancer cells to G2/M cell cycle arrest and increases p27 protein expression. An inverse relationship was also illustrated between total circulating carotenoid and the following cancers: bladder, breast, colorectal adenoma, and prostate (Wu et al. 2020; Eliassen et al., 2012; Jung et al. 2013). This signifies the medical applications of carotenoids in cancer therapy.

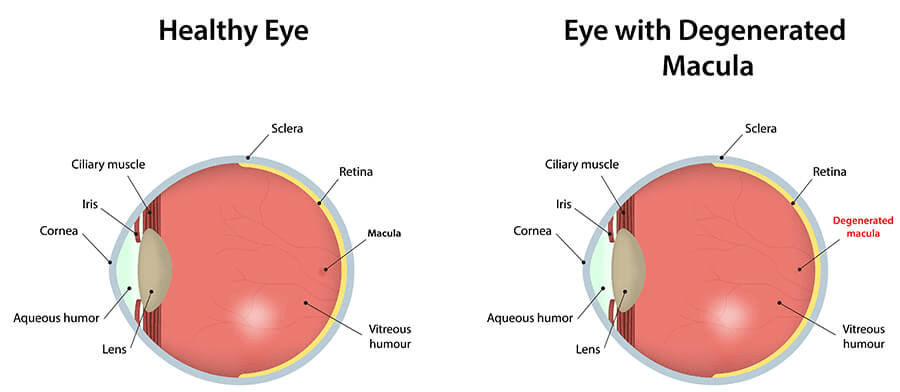

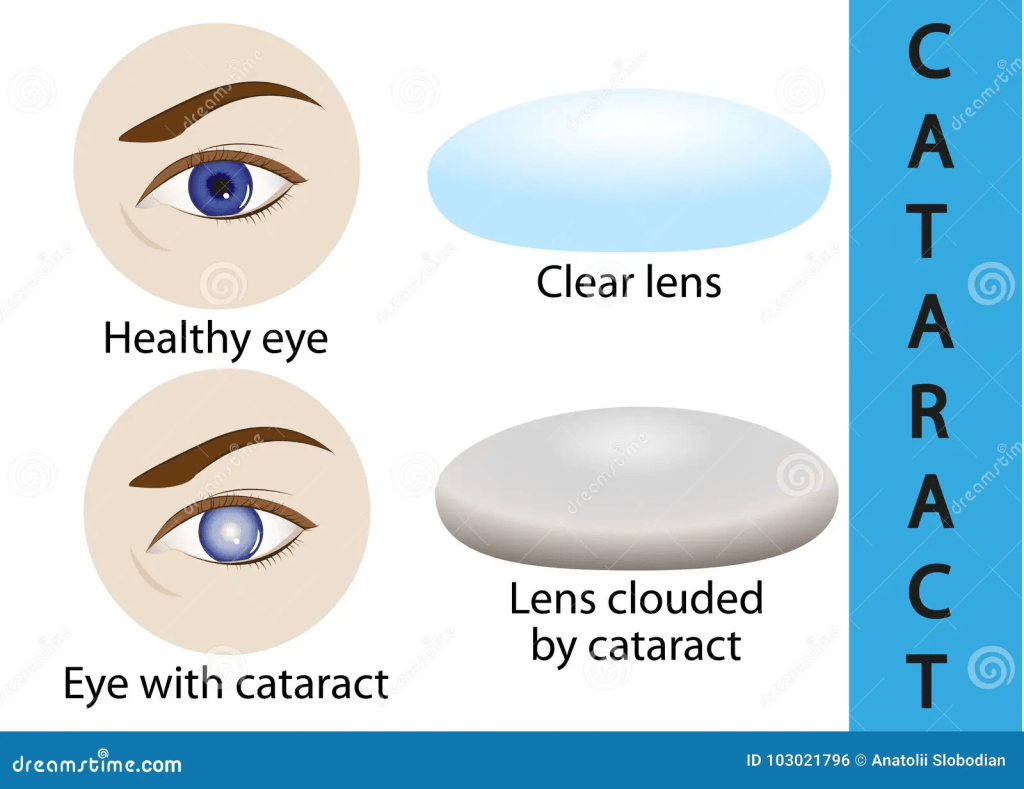

Carotenoids can also protect eyes from fatal non-cancerous conditions, for instance, cataracts and macular degeneration. Macular degeneration affects the macula lutea, a yellow spot on the retina at the back of the eye – please see Figure 19. A cataract is the cloudiness of the lens of the eye – please see Figure 20. Both conditions can limit vision.

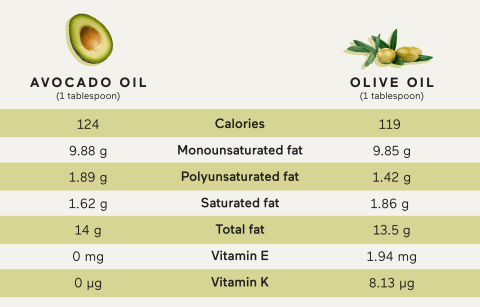

Furthermore, the high levels of monounsaturated fats in the avocado can help lutein and other bioactive carotenoids to be absorbed into the blood, lowering cancer risk (AlKhalaf et al., 2019). It is estimated that 17% of edible seed oils containing monounsaturated fats are found in the avocado seed (AlKhalaf et al., 2019). Please see Figure 21 that compares the content of avocado and olive oil. Both are similar nutritionally, however, olive oil consists of additional vitamins (Moore, 2023.

Chromatographic analysis by AlKhalaf et al. (2019) discovered the fruit extract was richer in oleic acid (75.16%) compared to the seed (25.3%). This corresponds to the weight of the avocado seed that contributes to ca. 15% of the total weight of the fruit. The results were consistent with Marovic et al. (2024), where oleic acid was most abundant in fresh avocados, with a concentration between 41.28% and 57.93%.

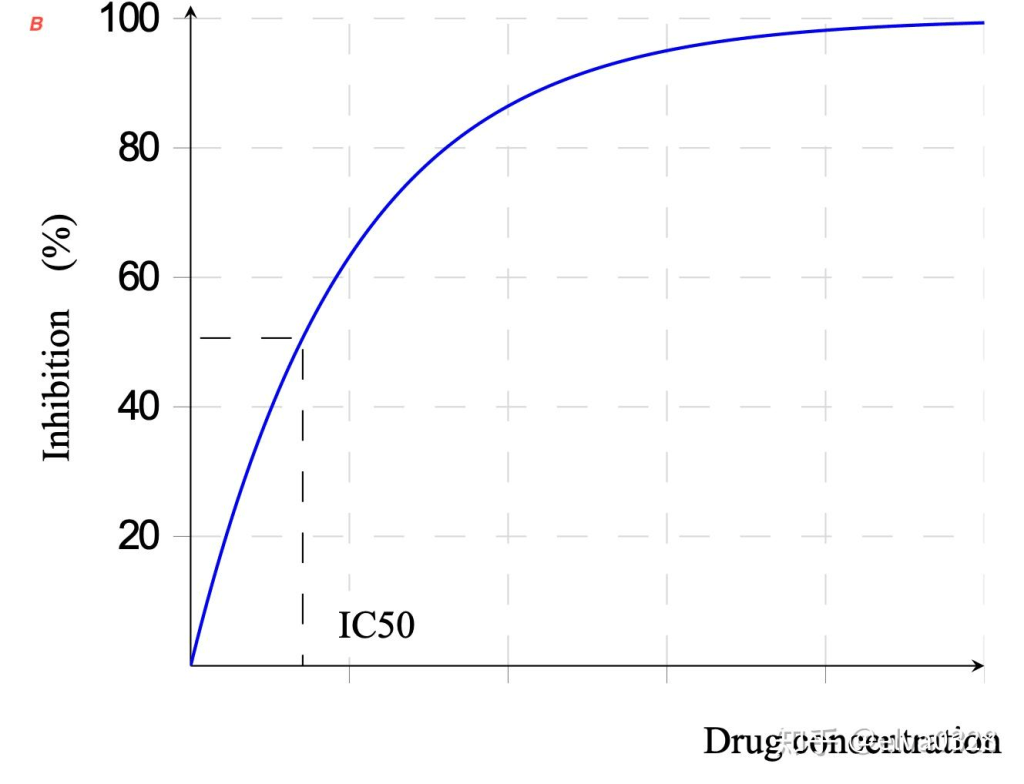

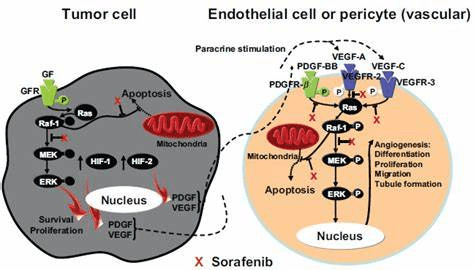

In vitro studies in colon and liver cancer cell lines detected the prevalence of anti-inflammatory and anti-tumour activities present in the seed and fruit extracts than the bulb. The inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) was in proximity to the reference values of Sorafenib (AlKhalaf et al. 2019). The IC50 is a quantitative measure of the concentration of a chemical required to prevent biological processes by 50% – please see Figure 22. Sorafenib is a multi-targeted small-molecule kinase inhibitor commonly used in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) – please see Figure 23. Inversely association between increased intake of monounsaturated fats and cancer risk was linked with decreased risk of oral, pancreatic, pharyngeal, and prostate cancer (Garavello et al., 2009; Ghamarzad et al, 2021; Dianatinisab et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2012). This highlights the potent effect of the neglected seed, which is commonly unutilized and non-edible.

Other parts of the avocado fruit have also presented cancer-preventative properties, where the leaf increased the formation of free oxygen radicals in patients with larynx carcinoma (Collignon et al., 2023). Another anti-cancer constituent in avocado is glutathione. This can lower the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer (Ericcson et al. 2023).

Lee et al. (2014) noticed that Avocatin B, a fat found in avocado, induces cell death in patients with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) without affecting normal peripheral blood stem cells, especially at concentrations as 20µM, and targets the mitochondria where it is oxidized into fatty acids. AML is an aggressive malignant disease where there are poor patient clinical outcomes and suboptimal chemotherapeutic response (Lee et al. 2014). Cells that do not contain mitochondria, an organelle involved in respiration to produce energy, were insensitive to Avocatin B. Similarly, cells that do not have the enzyme CPT1, whose normal function is to help transport mitochondrial lipids. Avocatin B can prevent oxidation of fatty acids and can decrease levels of the chemical compound Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) by 50%. NADPH is a co-factor produced during fatty acid oxidation that undergoes catabolic processes during cellular proliferation. This ultimately causes reactive oxygen species (ROS)- dependent death of leukaemia cells (Lee et al., 2014).

Moreover, Avocatin B induces cell death in primary AML cells with half maximal effective concentration (EC50), where there is a biological response halfway after a specified exposure time. The EC50 was within the range of 1.5 and 5.0 µM. This suggests Avocatin B is a useful anti-leukemic agent with selective toxicity causing apoptosis.

However, contrasting results were found in studies by the NHS, where multivariable analysis presented no direct proportionality between consuming avocado and lowering the risk of many site-specific cancers linked with women, except patients with breast cancer (Ericcson et al., 2023). Post-menopausal women, non-diabetic patients, and mammogram screening had a positive association with decreased incidence of avocado consumption. Similar results were also indicated in the large prospective study where Ericsson et al. (2023) revealed that men who consumed avocados had a significantly reduced risk of cancer compared to women.

Overall, the positive outcomes accomplished from the clinical studies signify that avocados’ nutritional profile is predominantly found in the seed, pith, pulp (mesocarp), and leaf extracts, with increased anti-carcinogenic properties and well-established benefits. Further randomized trials are needed to promote the anti-cancer properties of the avocado-derived phytochemicals.

Strawberries

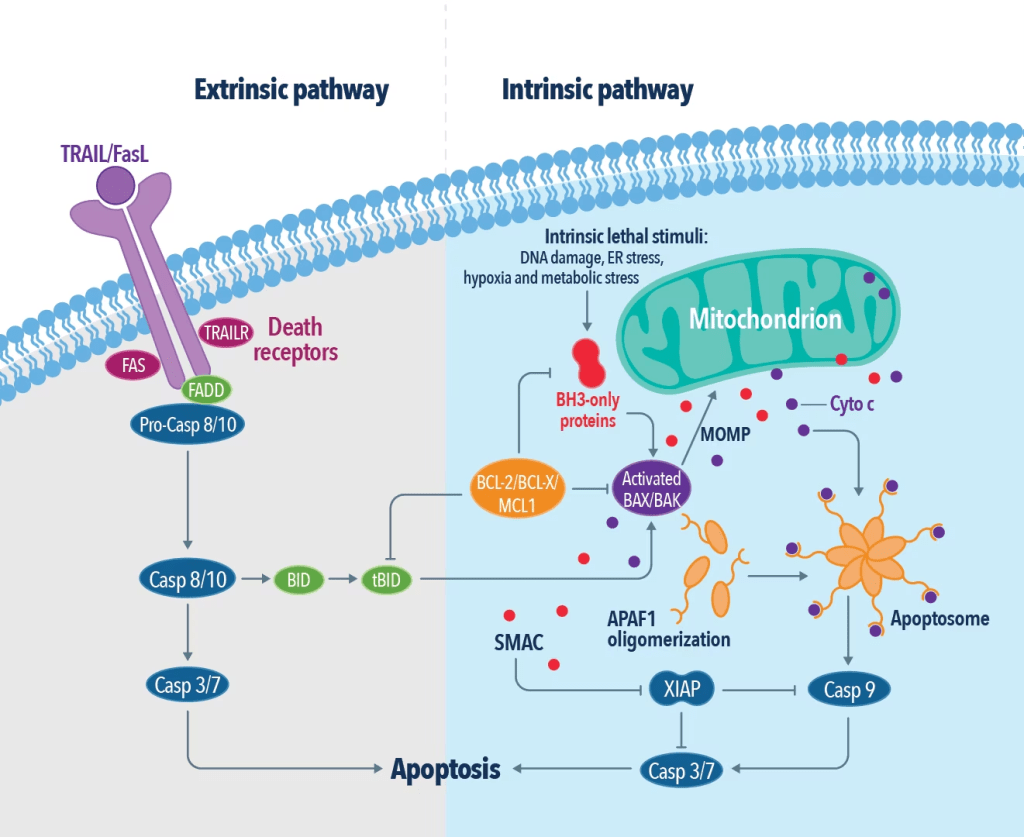

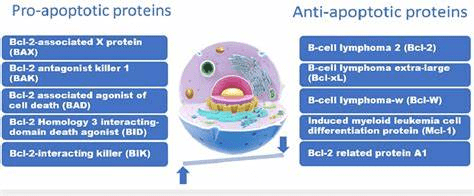

The anti-tumour effects of berries correlate with the concentration of polyphenols and induce oxidative stress. Key examples are Vitamin C, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and hydroxycinnamic acids. However, the definitive mechanism is unknown, where research studies suggest it can modulate genes and metabolise enzymes (Somasagara et al., 2012). Phytochemicals can also promote apoptosis (cell death) predominantly via the intrinsic pathways stimulated by DNA damage and generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) – please see Figure 24. Other mediators of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway are radiation and growth factors. The imbalance of the BCL2 family of preapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins can damage the mitochondrial membrane – please see Figure 25. The methanolic extract of the strawberry (MESB) increased the expression of the protein BAX and APAF1, causing the release of cytochrome C (cyto C) and activation of the enzyme Caspase 9 (Casp 9). This escalates the downstream signalling events of apoptosis.

Histological and immunohistochemical studies suggest MESB can modulate the expression of tumour suppressors, p73, and the mutation of p53 can activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway to halt cancer cell proliferation, especially in patients with breast cancer (Somasagara et al., 2012). This signifies that the mechanism of MESB has molecular and cellular significance.

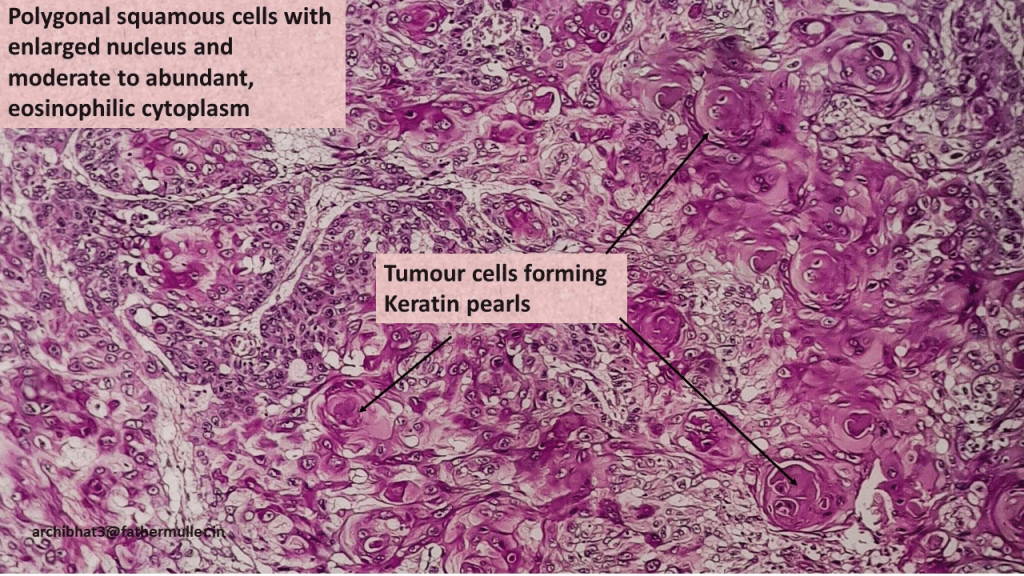

The toxic effects of the powerful carcinogen N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine (NMBA) were associated with the high incidence and mortality of patients with oesophageal cancer in developing countries. There are two subtypes of oesophageal cancer where higher rates are found in the oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma rather than oesophageal adenocarcinoma – please see Figure 26. Robust suppression of tumour multiplicity in the squamous epithelial cell population that lines the oesophagus (food pipe) when combining 5% strawberry extracts with 0.01% low-dose aspirin (75-81 mg/day) than alone.

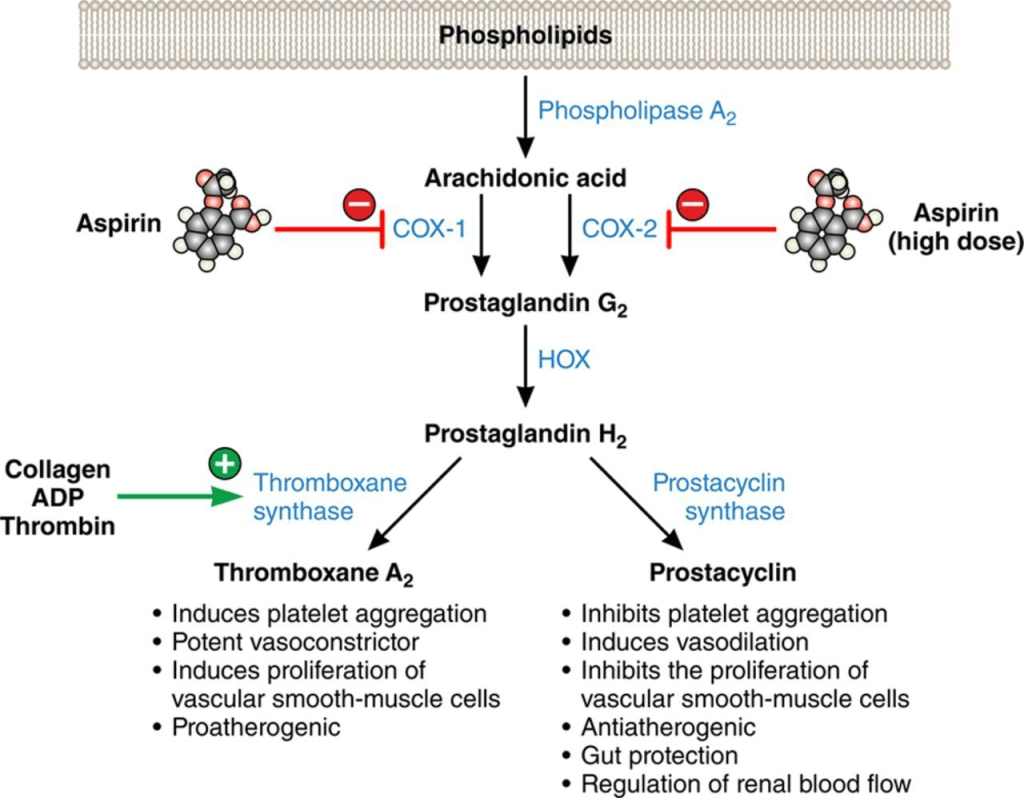

However, as a sole pharmacological agent, aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX-1), and COX-2 can evoke its protective effects in colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and cardiovascular disease (Pasche et al., 2014) – please see Figure 27. High doses of aspirin (325-600mg/day) have an analgesic effect (Pan et al., 2018). The essential role of COX is to produce prostaglandins, which are responsible for the inflammatory response (Eustice, 2024). COX-1 is predominantly in most tissues, especially the gastrointestinal tract, where it maintains the lining of the tract as a protective measure for the enzymes. Other contributing roles of COX-1 are to function in the kidney and platelets. In contrast, COX-2 preserves an inflammatory response (Eustice, 2024).

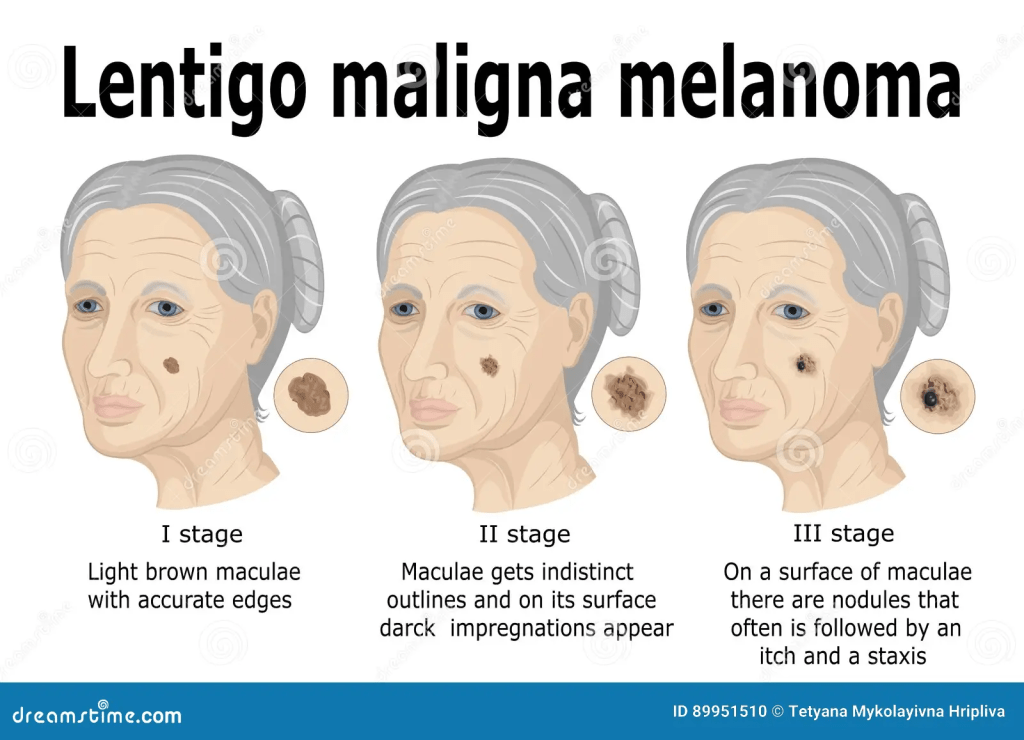

The recognition of the antiproliferative effects of strawberry was substantiated by evidence of its biological effects in patients with prostate cancer, gynaecological (cervical, ovarian), blood cancers (leukaemia), skin cancer (melanoma), and liver cancer (hepatoma) (Giampieri et al., 2017). The mechanism did not involve the enzymes, COX-1, and COX-2, nor alterations in the cell cycle regulation, despite evidence suggesting strawberries can inhibit COX-2 expression in the oesophagus (Chen et al., 2012).

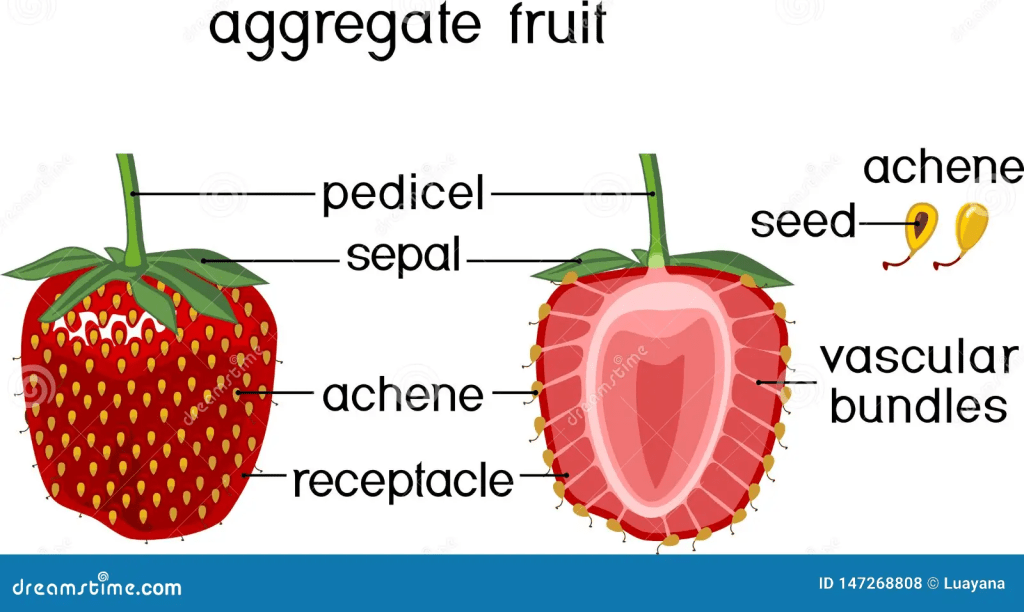

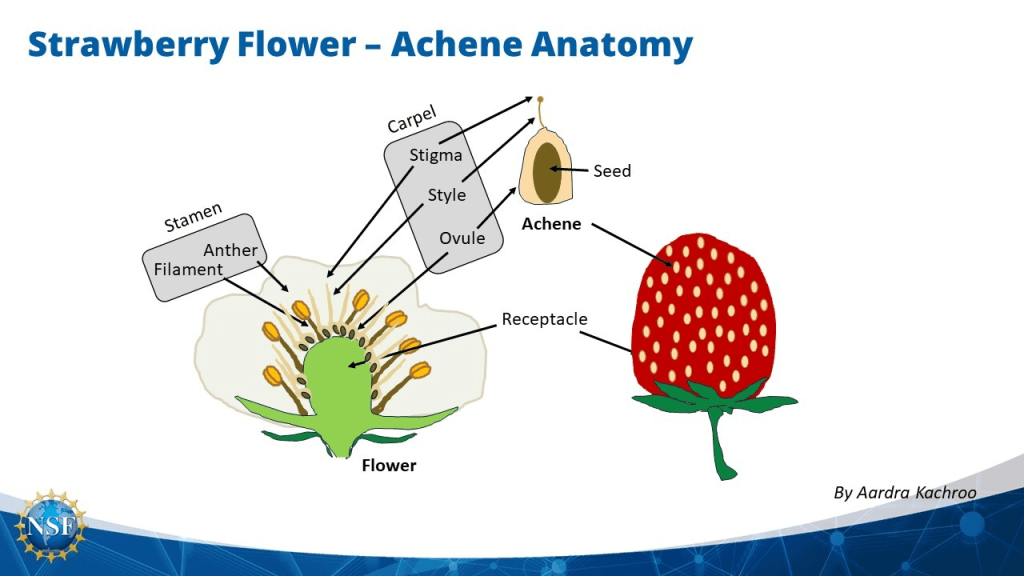

The nutraceutical potential of Ellagic acid appears to prevent the activation of carcinogenic substances into cellular toxins, causing them to lose their ability to react with DNA and induce mutations capable of triggering the onset of cancer. The phenolic compound derived from ellagitannin, found in plant cell vacuoles in free and bound forms in the seeds (achenes), nuts, fruits, especially berries – please see Figure 28. The concentration of total ellagic acid is between 0.63-0.70 mg/g in strawberries, but the highest level resides in black berries (Daniel et al., 1989; Williner, Pirovani, and Guemes, 2003; Muthukumaran et al., 2017).

Compiling evidence suggests that ellagic acid and total phenolic content (41.1%) are more concentrated in the achenes on the outer surface of the fruit rather than the pulp (Muthukumaran et al., 2017). The structure of the strawberries are presented in Figure 29. It may indicate there is a higher antioxidant capacity in the achenes than in other locations of the strawberry, where it is estimated within the range of 45 to 81% in comparison to the roots because of the low total phenolic concentration (Ariza et al., 2016; Simirgiotis and Schmeda-Hirschmann, 2010). In the realm of the health benefits of fruits, this research evidence proclaims the anti-carcinogenic properties of strawberries.

Acai Berries

The abundant presence of Acai in South and Central America is another example of a dietary berry whose extracts have anti-oxidant potential, inducing cancer cell death, particularly in patients with leukaemia over 24-hour period (Beatcancer.org, 2025). This is attributed to the high concentration of the non-nutritive bioactive phenolic compounds, anthocyanins. Other phytochemicals are also present at low concentration (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas, and Sikalidis, 2016). These antioxidants are found two-fold higher than in blueberries. Other beneficial contents of acai are lipids (48%), protein (13%), amino acids (8%), carbohydrate sugars and vitamins (A, B1, B2, B3, C and E) total composition of 25% (Alessandra-Perini et al., 2018).

Anthocyanins give acai berries a distinctive colour pigmentation and are localized in the skin, seeds, and leaves (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas and Sikalidis, 2016). The structure of the acai fruit is presented in Figure 25. The highest concentration of polyphenols is found in the seed (28.3%), and in descending order, whole fruit 25.5% and bark (15.7%). Synergistically, it also confers molecular and cellular protection against DNA damage, inflammation, preventing angiogenesis, and apoptosis.

In experimental cancer models, there was a reduction in tumour cell proliferation and the size of the tumours. In oesophageal cancer cells, there was a decrease in interleukin 5 and interleukin 8, but higher levels of interferon gamma following the addition of acai for 35 weeks. However, the serum levels of other interferons 1, 4, and 13, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha were merely affected by the presence of acai (Stoner et al., 2010).

Furthermore, there was a decreased expression of p63, Ki-67, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in post-acai treatment in bladder cancer cells. They are commonly involved in tumour progression, metastasis, and survival (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas and Sikalidis, 2016). This indicates the increased anti-proliferative capacity embedded in the acai. The addition of acai for 10 weeks did not affect the levels of beta-catenin (Fragoso et al., 2012). The pro-apoptotic mechanism involved activation and cleavage of caspase-3 and downregulation of Bcl2. This was observed in leukaemia and colon cancer cells. Conversely, immunohistochemical analysis decreased levels of caspase-3 in colon tissue. This demonstrates the discrepancy in identifying the state of the levels of caspase 3 post-Acai treatment.

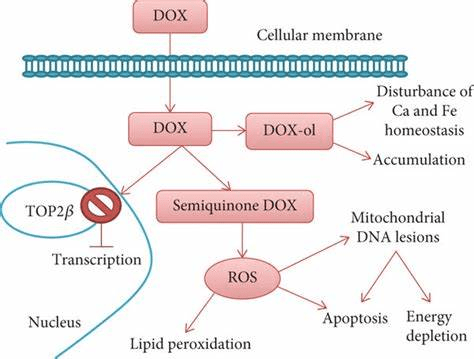

The antitumour potential of acai berries was also reported in other experimental models, such as melanoma and colon cancer – please see Figure 34. Acai berry altered its role in photosynthesis in melanoma, significantly increasing the necrotic tissue. Similarly, in colon cancer, there was a down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and COX-2 whereas Interferon gamma upregulates (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas, and Sikalidis, 2016). Toxicological studies revealed neither DNA damage nor genotoxic effects found in glioma and breast cancer. It has a protective effect on DNA damage induced by doxorubicin as an anthracycline – please see Figure 35. This illustrates the chemoprotective effects, notably antiproliferative, proapoptotic, and antioxidant, and the functional relevance of acai in cancer therapy (Kristo, Klimis-Zacas and Sikalidis, 2016).

Noni fruit

Morinda citrifolia, otherwise referred to as Noni, is a member of the Rubiaceae family; a small evergreen tree. Please see Figure 36. It contains carbohydrates, dietary fibers, niacin, calcium, iron, and potassium. Similar to the stated natural fruits, noni presents anti-cancer, antiangiogenesis, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory potential in experimental model studies (lung, cervical, and breast cancer cells). Apoptosis is stimulated by the AKT/NF-ĸb signalling pathway. Like acai berry, there is a downregulation of Ki67, PCNA, and BCL2, but increased expression of caspase 3. It can also affect cellular migration to prevent metastasis (Kumar et al. 2022).

There is minimal evidence on the side effects of noni on the human body, causing liver and kidney injuries due to hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, respectively. A Phase 1 clinical study discovered that a dose of 500 mg of noni fruit that was dehydrated, was administered to advanced cancer patients, can cause toxicity, but it is independent of the dose. This is concurrent with previous studies on the noni leaf and fruit extracts, where no liver injury was observed. Sufficient data on the safety and clinical efficacy are presented on Noni as a medicinal plant (Kumar et al., 2022).

Goji Berries

Mounting evidence reveals the medicinal application of Lycium Barbarum (Goji berry) as a cancer treatment and has been extensively used as a staple in traditional Chinese medicine to treat inflammatory and infectious diseases (National Foundation for Cancer Research, 2021; Sanghavi et al., 2023). One of the trace minerals found in goji berries is selenium, which acts as an antioxidant to neutralize free radicals that damage cells and cause cancer. Goji berries are also rich in other minerals like calcium, potassium, iron, zinc, and riboflavin.

The Goji berry contains high levels of phytoconstituents (flavonoids, beta-carotene, zeaxanthin) whose ethanolic extract fractions have been effective against breast carcinoma, oral, liver, colon, prostate, and cervix without affecting normal cells (Sanghavi et al., 2023). At a concentration of 100µg, the ethanolic extracts have decreased the viability of cancer cells by 65.5% compared to 91.7% of the control group. At 72 hours, a decrease in the migration of oral cancer cells was observed, where 42.8% of the wound remained (Sanghavi et al., 2023). This highlights its ability to control the adhesion of cancer cells.

In breast cancer cells, gogi modulates the metabolism of the oestrogen hormone, which stimulates the protein of extracellular signal-reduced kinase 1 and 2 (ERK) and increases expression of the tumour suppressor p53 (Wawruszak, Halasa and Okla, 2021). A decrease in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT elevates the antiproliferative activity. AKT stimulates and even inhibits the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins, e.g., Bad and Bax. The caspases involved in the apoptotic pathways are halted, increasing cancer survival.

Furthermore, there is concomitant downregulation of cyclin D1 and cadherin 2 and vimentin and upregulation of cadherin 1 in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition – please see Figure 40. The distinctive features between Epithelial and Mesenchymal cells are presented in Figure 41. This highlights the anti-invasive and anti-metastatic role of the Goji berry (Sanghavi et al. 2023).

Mangosteen

The existence of xanthones, a class of phytochemicals in the mangosteen fruit Garcinia mangostana, has reportedly exhibited pro-apoptotic and anti-tumour activities. Mangosteen is a purple tropical fruit native to Southeast Asia and is largely attributed to the outer white flesh/pulp called the pericarp. It contains 3 to 6 ovoid-oblong shaped seeds (Kalick et al., 2023). The pericarp, leaves, and seeds are said to decrease the size of tumours. However, research efforts are more interested in the roots, stem, and rind, shown effectiveness against T cell leukaemia (Kalick et al., 2023; Nauman and Johnson, 2021).

Mangostin is the most prominent xanthone that possesses great potency. They can modulate ROS and the proteins STAT3, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). STAT3 is a transcription factor that promotes apoptosis in gastric adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pancreatic cancer cells after α-mangostin (α-mangostin) treatment in vitro. (Nauman and Johnson, 2021). Cyclin-dependent kinases bind specifically with proteins called cyclins to regulate the cell cycle, Cancer cells can arrest at the G1 phase, significantly impacting the proliferation rate because it is a regulatory point that depends the fate for quiescence, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (Diehl, 2002). Matrix metalloproteinases, notably MMP-2 and MMP-9, increased levels, whilst E-cadherin decreased. This prevents migratory and invasive abilities (Nauman and Johnson, 2021).

Recent in vitro studies discovered that after a 6-hour treatment with α-mangstin, there was a decrease in oestrogen activity and expression of MAPK signalling proteins at concentrations > 6µM. There was a decrease in AKT and increased ERK1/2 to lower cell viability, independent of the MAPK pathway. The IC50 in breast cancer cells was between 2 and 3.5 µM after 24 and 48 hours. The IC50 is ca. two-fold higher in colon cancer, 7.5 µM. The combination of mangostin with the anti-metabolite 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), commonly used to treat solid tumours, resulted in a more potent effect to induce apoptosis and increase the levels of p53. The mode of action of 5-FU is presented in Figure 45.

Other secondary metabolites, gartanin, garcinone (C and E), β-mangostin, and γ-mangostin, found in the pericarp, stem, and roots, have hypothetically been shown to hold anticancer and antineoplastic effects against human malignancies, but their activity is not well understood.

Soursop

Soursop, otherwise known as Annona muricata or graviola, is a spiny, long green superfruit in the rain forests that reside in South East Asia, South America, the Caribbean, and Africa – please see Figure 46. Its pulp has a sweet, distinctive flavour (City of Hope, 2017). The leaves and soursop can irritate the stomach and cause fever.

The Soursop fruit has an array of nutrients to maximise the efficacy in killing cells of different types of cancer. This is supported by the high content of Vitamins (B and C) and the minerals (calcium, magnesium, iron, and phosphorus (National Foundation for Cancer Research, 2021; Cancer Research UK, 2022). The predominant phytochemical is annonaceous acetogenins and has exerted its chemopreventive effects utilising liver, prostate, and breast cancer cells. City of Hope (2017). Senior researched advise that laboratory studies claim Sousop eradicates the cancer cells, but has evidence of good safety and efficacy of its use (Oberlies, Chang, and McLaughlin, 1997).

Pomegranate

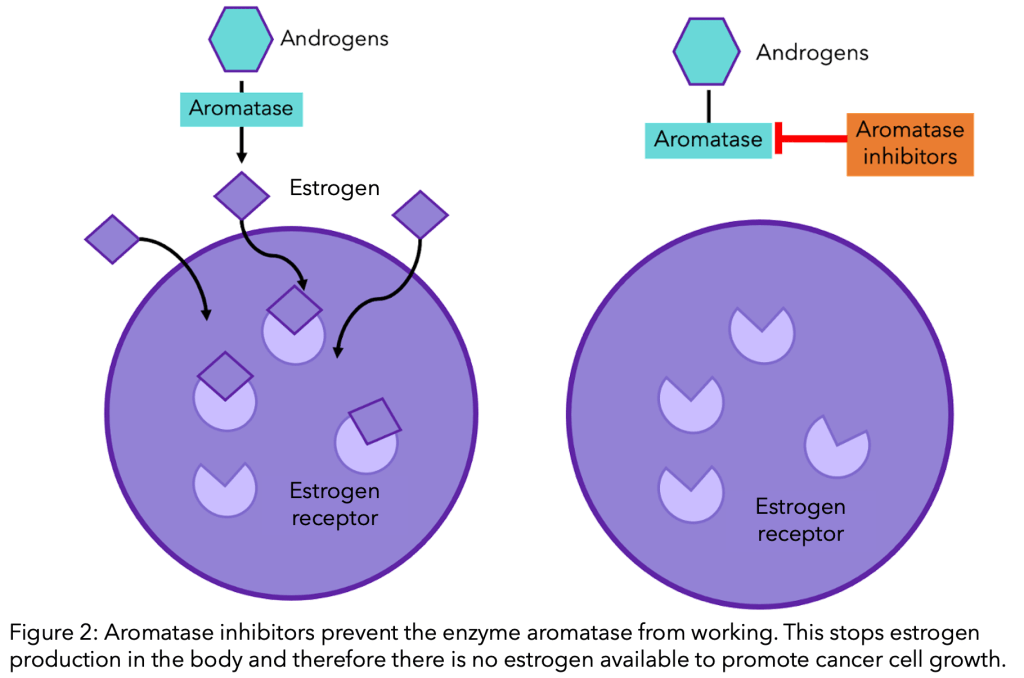

The high phenolic compounds present in pomegranate suppresses aromatase, an enzyme that converts androgen into estrogen, and was associated with the increased risk of breast cancer – please see Figure 48. The presence of ellagitannins releases the ellagic acid. Ellagic acid is converted into 3,8-dihydroxy-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-6-one, otherwise known as urolithin, by microorganisms present in the gut microflora. One of its subtypes, urolithin B, has presented potent inhibition of aromatase, lowering cancer cell proliferation in oestrogen-responsive breast cancers (Adams et al., 2010).

Furthermore, clinical trials have shown that pomegranate extracts can prevent prostate cancer in men. The profusion of Vitamin C and other antioxidants in pomegranates has shown preventative effects in patients with prostate cancer. The pomegranate juice is said to treat erectile dysfunction and high cholesterol. However, results are inconclusive, and further research is needed to determine its effectiveness (American Holistic Health Association, n.d.).

Kiwi Fruit

Actinidia deliciosa (Kiwi fruit) have been associated with favourable direct and indirect anticancer effects. The elevated levels of Vitamin C has significantly reduced DNA oxidative injury and induced cytotoxicity in several cancer cell lines in vitro. Amongst the hypothetical understanding is attributed to the increased bowel motion and presence of lactic acid-containing bacterial species in the faeces. Examples of normal, opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria found in the gut are illustrated in Figure 51. This lowers the risk of colorectal cancer and other malignancies (Lippi and Mattiuzzi, 2020).

A research study discovered that after a 24 hour incubation, Kiwi can ferment lactic acid bacteria lowering the simple sugars (glucose and fructose) and acidity (citric acid). One named example is Lactobacillus plantarum and has been found to increase the polyphenol content and other acids (succinic, lactic, acetic). This paradoxical state of Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation of kiwi fruit contributes to the kiwi suppression of cancer cells and are influenced by dose and time factors (Kim et al., 2025).

Further evidence also suggests that there are active compounds that can block the formation of carcinogenic “nitrosamines” in the human body. As a result, it has a good effect in preventing cancer. Amongst the negative effects of nitrosamine are presented in Figure 52.

Apple

Apples are globally consumed, particularly in Western diets, due to their multiple health benefits, price, storage conditions, and cultivar diversity. They are grown on trees – please see Figure 53 (Boyet and Liu, 2004). High content of phytochemicals in apples further emphasises the oncoprotective roles of fruits and vegetables. Amongst the examples of phytochemicals present in apples are triterpenoids. For instance, oleanolic, betulinic, and ursolic acid and their derivatives have potential anticancer benefits (Sut et al., 2018). They can inhibit cancer cell proliferation, promote apoptosis, and inhibit key molecules involved in other cancer hallmarks: invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis (Nezbedova et al., 2021).

The distribution, concentration, and type of phenols vary in the skin peel, seeds, flesh/pulp, and core, attributed to the growing conditions, location, harvest, storage, and genes. Nevertheless, most apples have a similar phenolic distribution (Nezbedova et al., 2021). The estimated concentration of phenol compounds is 22%, and free forms of its types are presented at a higher fold in apples than kiwi fruit, pear, plum, and peaches (Almeida et al., 2017). There are also variations in the types of apples: anthocyanidins that contribute to the pigmentation are found at elevated levels in ‘Red Delicious’ red apples, but a lower concentration in ‘Granny Smith’ green apples. Please see Figure 54 and 55 respectively.

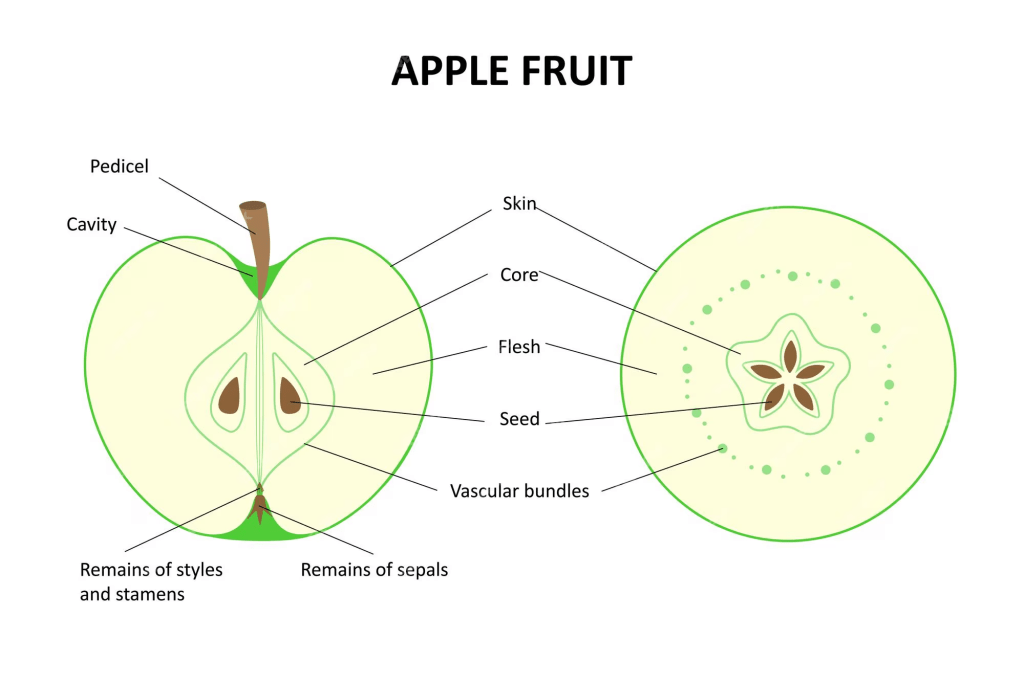

Moreover, the estimated content of some phenol compounds, for instance, anthrocyanidins, phenolic acids, and flavonols in the skin peel is 5%, 9%, and 18%, respectively. The weight of the peel contributes to 10% of the whole fruit. In contrast, the flesh has a higher concentration of phenolic acids (40%) and flavonols (56%) (Nezbedova et al., 2021). The structure of the apple is presented in Figure 56.

However, taking into consideration the total concentration of all the phenolic compounds in the skin peel, it is five times higher than in the flesh, but individual chemicals vary (Laaksonen et al., 2017). This indicates the variation in the bioactive compounds present in the apples.

Observational cohort analysis discovered that the consumption of a minimum of three apples and pears lowers the risk of breast cancer and pancreatic cancer, especially in pre-menopausal women (Rossi et al., 2012; Nezbedova et al., 2021; Torres-Sanchez et al., 2000). Descending incidence of other cancers presented, notably, colorectal, oral, head and neck cancers, oesophagus, renal, gynaecological, and prostate cancers (Nezbedova et al., 2021). This demonstrates the chemopreventative effects of apples by promoting apoptotic, antiangiogenic, anti-invasive, anti-metastatic, and anti-proliferative mechanisms.

On a molecular level, a myriad of phytochemicals increased the expression of the tumour suppressor gene, maspin. It prevents the activity of enzymes (CDK, ERK, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases) that facilitate cell cycle progression. They also limit the activity of p21 and growth factors (Reagan-Shaw et al., 2010; Nezbedova et al., 2021).

Increased oxygen potential is due to catechin and epicatechin, further increasing apoptosis in colon cancer cells (Hwang et al., 2007). Phloretin and phloridzin are metabolised in the human intestine and have anti-proliferative activity in breast and colon cancer cells. This is achieved by limiting the expression of glucose transporter 2 (Glut-2), cell cycle arrest, and decreased expression of proinflammatory molecules (IL-8, PGE2) (Zielinska et al., 2019). In in vivo studies, the efficacy of phloretin combined with Paclitaxel was further accelerated to promote an anti-inflammatory environment and prevent invasion and migration of cancer cells. (Yang et al., 2008).

Another abundant phenolic acid that demonstrates anti-proliferative behaviour is chlorogenic acid. It is metabolised in the large intestine by the gut microbiota. In vivo and in vitro studies revealed that it can downregulate MMP2 and MMP9, which suppresses invasion and metastasis. The expression of microRNA (miR-17) promotes cell cycle arrest. The suppression of the NF-KB pathway and specifically binding to annexin promotes apoptosis. All collectively suggest reasons why xenograft mice in vivo had a lower rate of liver and breast cancers (Sapio et al., 2020; Sadeghi Ekbatan et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2020).

Honey

The earliest records of beekeeping were in Cairo in 2400 BC. The Ancient Egyptians used honey as a sweetener and embalming fluid, whereas the Ancient Greeks observed honey as a healing medicine and an important food, as did other European countries. However, the introduction of sugar decreased the usage of honey as a sweetener; instead, it was employed for wounds, gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular and hepatic diseases.

There are more than 320 types of honey, and the aroma, colour, and scent depend on several determinants: the floral source it originates from, age, and storage conditions. The two main constituents of honey are sugar and water (Eteraf-Oskouei and Najafi, 2021). The viscosity of the liquid state is reflective of the chemical compounds it entails, water content, and hygroscopicity. Hygroscopicity is defined as the ability of honey to absorb and retain moisture from the environment. The volume of water is estimated to be 18.8% and can absorb moisture with relative humidity above 60% (Olaitan, Adeleke, and Ola, 2007).

Honey primarily consists of several sugars (percent/100 g): 38% fructose (monosaccharide), 47% glucose (monosaccharide), and 1% sucrose (disaccharide). The highest mineral content is potassium (52 mg/100g), and the least is iron (0.42 mg/100g). A simultaneous level of sodium and phosphorus (4 mg/100g) was also found.

The most abundant vitamin in honey is Vitamin C, with a concentration of 500 µg/100g. In descending order, Vitamin B3 (121 µg/100g), Vitamin B5 (68 µg/100g), Vitamin B2 (38 µg/100g), Vitamin B6 (24 µg/100g), and lastly Vitamin B9 Folate (2 µg/100g). Other constituents present in the honey are miscellaneous compounds, amino acids, proteins, and enzymes, mainly glucose oxidase, invertase, and diastase (Eteraf-Oskouei and Najafi, 2013; Ahmed and Othman, 2013).

One of the prominent uses of honey can be illustrated in the golden nectar of Yemeni sidr honey, which has medicinal and culinary uses that date back centuries – please see Figure 58. It contains Vitamins (B, and C) and minerals (calcium, iron, and potassium) that increase vitality – please see Figure 58. Its extensive antioxidant and antimicrobial content helps overcome wounds, infections, heart disease, and cancer and can boost the immune system and overall health (Behalalorganics, 2025).

There has been recent studies on the disadvantages of the chemotherapeutic agents is the impact on quality of life (QoL) and toxic side effects. Therefore, therapies including honey that can lower cancer progression and decrease the dose administered by these anti-cancer drugs are needed (Porcza, Simms, and Chopra, 2016). In vivo studies in rats with breast cancer induced by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea detected that the positive effects of Manuka honey were greater than Tualang honey (Othman, Ahmed, and Sulaiman, 2016). Manuka honey illustrated in Figure 59 was observed to increase apoptotic activity by activating the enzyme caspase 3 and depolarise the mitochondrial membrane, upregulate the tumour suppressor p53, and downregulate Bax and Bcl2 proteins. It also elevated poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) for DNA repair. This suggests the role of phenolic contents and tryptophan in promoting apoptosis (Jagnathan and Mandal, 2013).

Similarly, upon treatment with Iranian honey, there was a significant reduction in the size of the tumour and angiogenic potential in breast cancer induced by 7, 12-dimethylbenz (a) anthracene (DMBA) (Eteraf-Oskouei and Najafi, 2013). An image of Iranian sidr honey is pictured in Figure 60.

Other studies revealed that prophylactic treatment with honey increased the levels of lymphocytes, peritoneal macrophages, and immunoglobulins (A, M, and G). Other types of honey, such as the Nigerian jungle honey, possess chemotaxis for neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. An image of African honey is presented in Figure 61. This signifies that honey propagates the immune system to combat cancer cells and demonstrates the impact of a variety of honeys (Attia et al., 2008).

High amounts of polyphenols in Gelam honey, a Malaysian monofloral honey, have antioxidant potential – please see Figure 62. The IC50 concentration was more effective in decreasing the growth of normal human liver cells (70%) than HepG2 cancer cells (25%) (Jubri et al., 2012). Honey also showed protection against DNA damage induced by dietary mutagens in HepG2 cancer cells in vitro. Antiproliferative effects were also presented in colon cancer cells in vitro (Wen et al., 2012). This highlights how honey contains polyphenols that work effectively as a synergistic antioxidant, as well as flavonoids, catalase, and ascorbic acid as contributory factors. Honey has anti-neoplastic activity against other cancers, such as bladder, endometrial, cervical, oral, and osteosarcoma, and prostate and leukaemia (Ahmed and Othman, 2013; Jagmathan, 2009).

On the contrary, some types of honey have biphasic behaviour and depend on their concentration. For instance, low concentrations of honey containing Greek thyme, fir, and pine extracts picture in Figure 63 suppress the hormonal action of oestrogen and increase oestrogen activity at higher concentrations. This somehow correlated with the cell viability of breast cancer cells, where fir honey presented a rise in the cancer cell population; on the contrary, pine and thyme honey had no profound effect on cell viability (Tsiapara et al., 2009). The biphasic behaviour corresponds to the concentration of quercetin and kaempferol phenolic compounds present in the honey (Eteraf-Oskouei and Najafi, 2013).

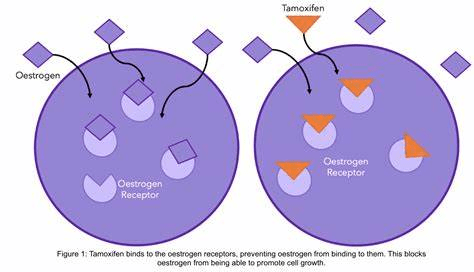

A similar biphasic behaviour was observed in in vitro studies. In a non-tumour breast cell line (MCF-10A), Tualang honey diminished the anti-tumour effects of 4-hydroxymatrine. An image of Tualang honey is presented in Figure 64. However, in breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-23), there were potent antiproliferative effects. This demonstrates the augmentation of Tualan honey on the mechanistic action of Tamoxifen on cancer cells whilst protecting healthy cells (Yaacob and Ismail, 2014; Yaacob, Nengsih, and Norazmi, 2013). The mode of action of Tamoxifen is presented in Figure 65. The potentiation of honey to induce antitumour activity of other chemotherapeutic agents was also mirrored in 5-fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide (Gribel and Pashinskiĭ, 1990).

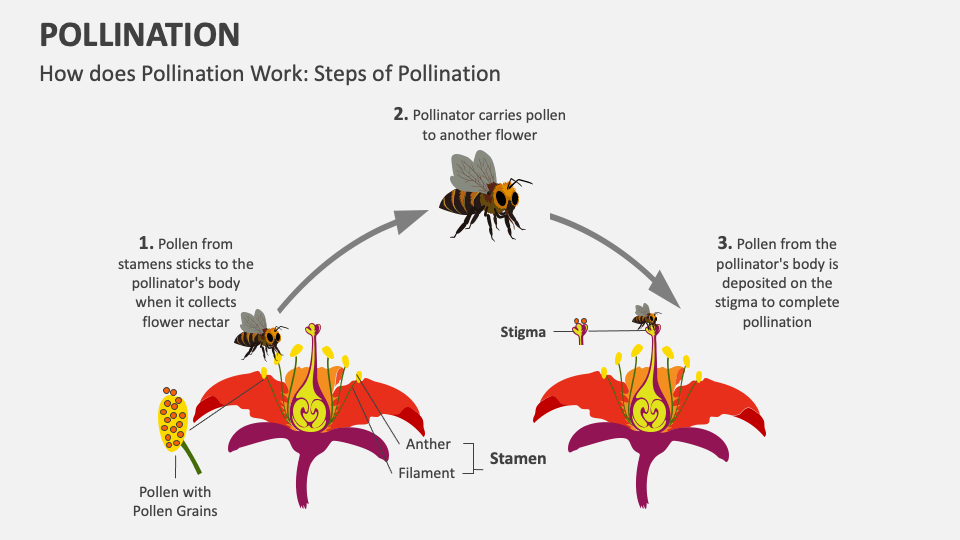

There is minimal evidence of any toxicity produced by Natural honey, however, topical application may cause a stinging sensation, and there are rare cases of allergy. Dehydration may rise if honey is overused and can substantially increase blood glucose levels if applied to open wounds. The method of production and collection may also increase risk; for instance, honey is commonly produced by heat or sterilization, and this can lead to the synthesis of a potential carcinogenic agent, such as hydroxymethyl furfural (HMF). Bee pollination may come into contact with air, soil, and water in the environment, such as lead, mercury, cobalt, and other heavy metals that can affect human health. The general process of bee pollination is presented in Figure 66. Overall, anti-cancer mechanisms of honey have been elucidated, and further studies are needed to emphasize its clinical use.

In conclusion, interdisciplinary researchers have observed groundbreaking discoveries in experimental cancer models in vivo and in vitro that support the idea that dietary fruits and vegetables help to reduce cancer risk in combination with conventional therapeutic modalities. The protein, cellular, and molecular evolution has swiftly progressed over the years, leading to a better understanding of cancer signalling pathways, DNA repair, mechanisms to escape the immune system, apoptosis, and other hallmarks of cancer (Wellstein, 2018). The presence of secondary metabolites, phytochemicals in fruits, have anticancer activity that is inversely correlated with inflammatory markers and overcomes oxidative damage. This in turn, exerts its anti-proliferation and anti-neoplastic effects. Phytochemicals also hold additional roles in the taste, colour, and aroma. Further studies in natural products are needed to design new cancer treatments.

References

Adams, L.S., Zhang, Y., Seeram, N.P., Heber, D. and Chen, S. (2010). Pomegranate Ellagitannin-Derived Compounds Exhibit Antiproliferative and Antiaromatase Activity in Breast Cancer Cells In vitro. Cancer Prevention Research, [online] 3(1), pp.108–113.

Ahmed, S. and Othman, N.H. (2013). Honey as a Potential Natural Anticancer Agent: A Review of Its Mechanisms. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : eCAM, [online] 2013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/829070.

Alessandra-Perini, J., Rodrigues-Baptista, K.C., Machado, D.E., Nasciutti, L.E. and Perini, J.A. (2018). Anticancer potential, molecular mechanisms and toxicity of Euterpe oleracea extract (açaí): A systematic review. PLoS ONE, [online] 13(7), p.e0200101.

Alkhalaf, M.I., Alansari, W.S., Ibrahim, E.A. and ELhalwagy, M.E.A. (2019). Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of avocado (Persea americana) fruit and seed extract. Journal of King Saud University – Science, 31(4), pp.1358–1362.

Almeida, D.P.F., Gião, M.S., Pintado, M. and Gomes, M.H. (2017). Bioactive phytochemicals in apple cultivars from the Portuguese protected geographical indication ‘Maçã de Alcobaça:’ Basis for market segmentation. International Journal of Food Properties, 20(10), pp.2206–2214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2016.1233431.

American Holistic Health Association (n.d.) Anticancer Effects of Pomegranate. Available at: https://ahha.org/xresearch-articles/anticancer-effects-of-pomegranate/ (Accessed: 20th May 2025)

American Institute for Cancer Research (2021) Grapes: Resveratrol and More. Available at: https://www.aicr.org/cancer-prevention/food-facts/grapes/ (Accessed: 18th May 2025)

Archer, S., Meng, S., Wu, J., Johnson, J., Tang, R. and Hodin, R. (1998) Butyrate inhibits colon carcinoma cell growth through two distinct pathways. Surgery 124: 248-253.

Ariffin, A. A., Bakar, J., Tan, C. P., Rahman, R. A., Karim, R. and Loi, C. C. (2009) Essential fatty acids of pitaya (dragon fruit) seed oil. Food Chemistry 14(2): 561 564.

Ariza, M.T., Reboredo-Rodríguez, P., Mazzoni, L., Forbes-Hernández, T.Y., Giampieri, F., Afrin, S., Gasparrini, M., Soria, C., Martínez-Ferri, E., Battino, M. and Mezzetti, B. (2016). Strawberry Achenes Are an Important Source of Bioactive Compounds for Human Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 17(7), p.1103.

Attia, W.Y., Gabry, M.S., El-Shaikh, K.A. and Othman, G.A (2008) The anti-tumour effect of bee honey in Ehrlich ascite tumor model of mice is coincided with stimulation of the immune cells. Egyptian Journal of Immunology.15(2): pp.169–83

Be Halal Organics (2025) Yemeni Sidr Honey: Unlocking its Marvelous Health Benefits. Available at: https://behalalorganics.com/blog/yemeni-sidr-honey-unlocking-its-marvelous-health-benefits/ (Accessed:24th May 2025)

BeatCancer.org (2023) New Research Reveals the Anti-Cancer Properties of Acai Berries. Available at: https://beatcancer.org/blog/new-research-reveals-the-anti-cancer-properties-of-acai-berries/ (Accessed: 19th May 2025)

Boyer, J. and Liu, R.H. (2004). Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits. Nutrition Journal, 3(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-3-5.

Cancer Research UK (2022) Graviola (soursop). Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/complementary-alternative-therapies/individual-therapies/graviola (Accessed: 20th May 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2022) Herbal Medicine and Cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/complementary-alternative-therapies/individual-therapies/herbal-medicine (Accessed: 18th May 2025)

Chen, T., Yan, F., Qian, J., Guo, M., Zhang, H., Tang, X., Chen, F., Stoner, G.D. and Wang, X. (2011). Randomized Phase II Trial of Lyophilized Strawberries in Patients with Dysplastic Precancerous Lesions of the Esophagus. Cancer Prevention Research, 5(1), pp.41–50.

City of Hope (2017) Experts warn against using soursop to fight cancer. Available at:

Collignon, T. E., Webber, K., Piasecki, J., Rahman, A. S. W., Mondal, A., Barbalho, S. M., & Bishayee, A. (2023). Avocado (Persea americana Mill) and its phytoconstituents: potential for cancer prevention and intervention. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 64(33), pp. 13072–13092.

Cutler, G.J., Nettleton, J.A., Ross, J.A., Harnack, L.J., Jacobs, D.R., Scrafford, C.G., Barraj, L.M., Mink, P.J. and Robien, K. (2008). Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of cancer in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study. International Journal of Cancer, 123(3), pp.664–671.

D’Ambrosio, S.M., Han, C., Pan, L., Kinghorn, A.D. and Ding, H. (2011). Aliphatic acetogenin constituents of avocado fruits inhibit human oral cancer cell proliferation by targeting the EGFR/RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 409(3), pp.465–469.

Daniel, E.M., Krupnick, A.S., Heur, Y.-H., Blinzler, J.A., Nims, R.W. and Stoner, G.D. (1989). Extraction, stability, and quantitation of ellagic acid in various fruits and nuts. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, [online] 2(4), pp.338–349.

Dasaesamoh, R., Youravong, W. and Wichienchot, S. (2016). Digestibility, fecal fermentation and anti-cancer of dragon fruit oligosaccharides. International Food Research Journal 23 (6) pp. 2581-2587.

Dianatinasab, M., Wesselius, A., Salehi‐Abargouei, A., Yu, E.Y.W., Fararouei, M., Brinkman, M., van den Brandt, P., White, E., Weiderpass, E., Le Calvez‐Kelm, F., Gunter, M.J., Huybrechts, I. and Zeegers, M.P. (2022). Dietary fats and their sources in association with the risk of bladder cancer: A pooled analysis of 11 prospective cohort studies. International Journal of Cancer, 151(1), pp.44–55. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of cancer in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study

Diehl, J.A. (2002). Cycling to Cancer with Cyclin D1. Cancer Biology & Therapy, 1(3), pp.226–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.4161/cbt.72.

Dreher, M.L. and Davenport, A.J. (2013). Hass Avocado Composition and Potential Health Effects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, [online] 53(7), pp.738–750. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of cancer in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study

Eliassen, A.H., Hendrickson, S.J., Brinton, L.A., Buring, J.E., Campos, H., Dai, Q., Dorgan, J.F., Franke, A.A., Gao, Y., Goodman, M.T., Hallmans, G., Helzlsouer, K.J., Hoffman-Bolton, J., Hultén, K., Sesso, H.D., Sowell, A.L., Tamimi, R.M., Toniolo, P., Wilkens, L.R. and Winkvist, A. (2012). Circulating Carotenoids and Risk of Breast Cancer: Pooled Analysis of Eight Prospective Studies. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 104(24), pp.1905–1916.

Ericsson, C.I., Pacheco, L.S., Romanos-Nanclares, A., Ecsedy, E., Giovannucci, E.L., Eliassen, A.Heather., Mucci, L.A. and Fu, B.C. (2022). Prospective Study of Avocado Consumption and Cancer Risk in US Men and Women. Cancer Prevention Research. 16(4), pp. 211-218

Eteraf-Oskouei, T. and Najafi, M. (2013). Traditional and modern uses of natural honey in human diseases: a review. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 16(6), pp. 731-42.

Eteraf-Oskouei, T. and Najafi, M. (2021). Uses of Natural Honey in Cancer: An Updated Review. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin. doi:https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2022.026.

Eustice, C. (2024) An Overview of Cyclooxygenase (COX). Available at: https://www.verywellhealth.com/cyclooxygenase-cox-1-and-cox-2-2552188 (Accessed: 19th May 2025)

Fragoso, M.F., Prado, M.G., Barbosa, L., Noeme Sousa Rocha and Luis Fernando Barbisan (2012). Inhibition of mouse urinary bladder carcinogenesis by açai fruit (Euterpe oleraceae Martius) intake. Plant Foods Human Nutrition, 67(3) pp:235:41.

Garavello, W., Lucenteforte, E., Bosetti, C. and Vecchia, C.L. (2009). The role of foods and nutrients on oral and pharyngeal cancer risk. Minerva Stomatologica, 58(1-2), pp.25–34.

Ghamarzad Shishavan, N., Masoudi, S., Mohamadkhani, A., Sepanlou, S.G., Sharafkhah, M., Poustchi, H., Mohamadnejad, M., Hekmatdoost, A. and Pourshams, A. (2021). Dietary intake of fatty acids and risk of pancreatic cancer: Golestan cohort study. Nutrition Journal, 20(1).

Giampieri, F., Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y., Gasparrini, M., Afrin, S., Cianciosi, D., Reboredo-Rodriguez, P., Varela-Lopez, A., Quiles, J.L., Mezzetti, B. and Battino, M. (2017). The healthy effects of strawberry bioactive compounds on molecular pathways related to chronic diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1398(1), pp.62–71.

Hwang, J.-T., Ha, J., Park, I.-J., Lee, S.-K., Baik, H.W., Kim, Y.M. and Park, O.J. (2007). Apoptotic effect of EGCG in HT-29 colon cancer cells via AMPK signal pathway. Cancer Letters, [online] 247(1), pp.115–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.030.

Jackson, M.D., Walker, S.P., Simpson-Smith, C.M., Lindsay, C.M., Smith, G., McFarlane-Anderson, N., Bennett, F.I., Coard, K.C.M., Aiken, W.D., Tulloch, T., Paul, T.J. and Wan, R.L. (2011). Associations of whole-blood fatty acids and dietary intakes with prostate cancer in Jamaica. Cancer Causes & Control, 23(1), pp.23–33.

Jaganathan, S.K. (2009). Honey Constituents and their apoptotic effect in colon cancer cells. Journal of ApiProduct and ApiMedical Science, 1(2), pp.29–36.

Jubri, Z., Narayanan, N.N.N., Abdul Karim, N. and Ngah, W.Z.W. (2012). Antiproliferative Activity and Apoptosis Induction by Gelam Honey on Liver Cancer Cell Line. International Journal of Applied Science and Technology 2(4), pp. 135-141.

Jung, S., Wu, K., Giovannucci, E., Spiegelman, D., Willett, W.C. and Smith-Warner, S.A. (2013). Carotenoid intake and risk of colorectal adenomas in a cohort of male health professionals. Cancer Causes & Control, 24(4), pp.705–717.

Kalick, L.S., Khan, H.A., Maung, E., Baez, Y., Atkinson, A.N., Wallace, C.E., Day, F., Delgadillo, B.E., Mondal, A., Watanapokasin, R., Barbalho, S.M. and Bishayee, A. (2023). Mangosteen for malignancy prevention and intervention: Current evidence, molecular mechanisms, and future perspectives. Pharmacological Research, 188, p.106630.

Kim, H.G., Park, W.L., Min, H.J. et al. Antioxidant and anticancer effects of kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa) fermented beverage using Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Sci Biotechnol 34, 207–216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-024-01643-8

Kristo, A., Klimis-Zacas, D. and Sikalidis, A. (2016). Protective Role of Dietary Berries in Cancer. Antioxidants, 5(4), p.37. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5040037.

Kumar, H.C., Lim, X.Y., Mohkiar, F.H., Suhaimi, S.N., Shafie, N.M. and Tan, T.Y.C. (2022). Efficacy and Safety of Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni) as a Potential Anticancer Agent. Integrative Cancer Therapies, [online] 21.

Laaksonen, O., Kuldjärv, R., Paalme, T., Virkki, M. and Yang, B. (2017). Impact of apple cultivar, ripening stage, fermentation type and yeast strain on phenolic composition of apple ciders. Food Chemistry, 233, pp.29–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.067.

Lee, E.A., Angka, L., Rota, S.-G., Hanlon, T., Hurren, R., Wang, X.M., Gronda, M., Bernard, D., Minden, M.D., Mitchell, A., Edginton, A., Sriskanthadevan, S., Datti, A., Wrana, J., Joseph, J.W., Quadrilatero, J., Schimmer, A.D. and Spagnuolo, P.A. (2014). Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation with Avocatin B Selectively Targets AML Cells and Leukemia Stem Cells. Blood, 124(21), pp.268–268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v124.21.268.268.

Lippi, G. and Mattiuzzi, C. (2019). Kiwifruit and Cancer: An Overview of Biological Evidence. Nutrition and Cancer, 72(4), pp.547–553.

Lu, Q.-Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, D., Lee, R., Gao, K., Byrns, R. and Heber, D. (2009). California Hass Avocado: Profiling of Carotenoids, Tocopherol, Fatty Acid, and Fat Content during Maturation and from Different Growing Areas. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 57(21), pp.10408–10413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jf901839h.

Modglin, L. (2023) Exploring Natural Remedies for Cancer Treatment. Available at: https://www.patientpower.info/navigating-cancer/natural-remedies-cancer (Accessed: 18th May 2025)

Moore, A. (2023) Olive Oil vs. Avocado Oil: A Breakdown Of Each + Which Is Healthier Available at: https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/olive-oil-vs-avocado-oil (Accessed: 24th May 2025)

Muthukumaran, S., Tranchant, C., Shi, J., Ye, X. and Xue, S.J. (2017). Ellagic acid in strawberry (Fragaria spp.): Biological, technological, stability, and human health aspects. Food Quality and Safety, 1(4), pp.227–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyx023.

National Federation for Cancer Research (2021) 5 Exotic fruits that giht cancer and where you can travel to ftry them. Available at: https://www.nfcr.org/blog/5-exotic-fruits-that-fight-cancer-where-you-can-travel-try-them/ (Access:18th May 2025)

Nauman, M.C. and Johnson, J.J. (2021). The purple mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana): Defining the anticancer potential of selected xanthones. Pharmacological Research, p.106032. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106032.

Neuhouser, M.L. (2004). Review: Dietary Flavonoids and Cancer Risk: Evidence From Human Population Studies. Nutrition and Cancer, 50(1), pp.1–7.

Nezbedova, L., McGhie, T., Christensen, M., Heyes, J., Nasef, N.A. and Mehta, S. (2021). Onco-Preventive and Chemo-Protective Effects of Apple Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients, 13(11), p.4025. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114025.

Olaitan, P.B., Adeleke, O.E. and Ola, I.O. (2007). Honey: a reservoir for microorganisms and an inhibitory agent for microbes. African health sciences, [online] 7(3), pp.159–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.5555/afhs.2007.7.3.159.

Oluwole, S., Yusuf, K., Fajana, O. and Olaniyan, D. (2013) Qualitative Studies on Proximate Analysis and Characterization of Oil From Persea Americana (Avocado Pear). Journal of Natural Science Research 3(2), pp. 68-73.

Othman, N.H., Ahmed, S. and Sulaiman, S.A. (2016). Inhibitory effects of Malaysian tualang honey and Australian/New Zealand Manuka honey in modulating experimental breast cancers induced by n-methyl-n-nitrosourea (mnu): A comparative study. Pathology, 48, p.S148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2015.12.403.

Pan, P., Peiffer, D.S., Huang, Y.-W., Oshima, K., Stoner, G.D. and Wang, L.-S. (2018). Inhibition of the development of N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced esophageal tumors in rats by strawberries and aspirin, alone and in combination. Journal of Berry Research, 8(2), pp.137–146.

Pasche, B., Wang, M., Pennison, M. and Jimenez, H. (2014). Prevention and Treatment of Cancer With Aspirin: Where Do We Stand? Seminars in Oncology, [online] 41(3), pp.397–401.

Porcza, L., Simms, C. and Chopra, M. (2016). Honey and Cancer: Current Status and Future Directions. Diseases, 4(4), p.30. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases4040030.

Reagan-Shaw, S., Eggert, D., Mukhtar, H. and Ahmad, N. (2010). Antiproliferative Effects of Apple Peel Extract Against Cancer Cells. Nutrition and Cancer, 62(4), pp.517–524. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01635580903441253.

Roko Marović, Marija Badanjak Sabolović, Mladen Brnčić, Antonela Ninčević Grassino, Kljak, K., Voća, S., Sven Karlović and Suzana Rimac Brnčić (2024). The Nutritional Potential of Avocado by-Products: A Focus on Fatty Acid Content and Drying Processes. Foods, 13(13), pp.2003–2003.

Rossi, M., Lugo, A., Pagona Lagiou, Antonella Zucchetto, Polesel, J., Serraino, D., Negri, E., Dimitrios Trichopoulos and Carlo La Vecchia (2012). Proanthocyanidins and other flavonoids in relation to pancreatic cancer: a case–control study in Italy. Annals of Oncology, 23(6), pp.1488–1493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr475.

Sadeghi Ekbatan, S., Li, X.-Q., Ghorbani, M., Azadi, B. and Kubow, S. (2018). Chlorogenic Acid and Its Microbial Metabolites Exert Anti-Proliferative Effects, S-Phase Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Colon Cancer Caco-2 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(3), p.723. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030723.

Sanghavi, A., Ananth Srivatsa, Divya Adiga, Chopra, A., Lobo, R., Shama Prasada Kabekkodu, Shivaprasada Gadag, Nayak, U., Sivaraman, K. and Shah, A. (2023). Goji berry (Lycium barbarum) inhibits the proliferation, adhesion, and migration of oral cancer cells by inhibiting the ERK, AKT, and CyclinD cell signaling pathways: an in-vitro study. F1000Research, [online] 11, pp.1563–1563.

Sapio, L., Salzillo, A., Illiano, M., Ragone, A., Spina, A., Chiosi, E., Pacifico, S., Catauro, M. and Naviglio, S. (2019). Chlorogenic acid activates ERK1/2 and inhibits proliferation of osteosarcoma cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 235(4), pp.3741–3752.

Simirgiotis, M.J. and Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. (2010). Determination of phenolic composition and antioxidant activity in fruits, rhizomes and leaves of the white strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis spp. chiloensis form chiloensis) using HPLC-DAD–ESI-MS and free radical quenching techniques. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 23(6), pp.545–553.

Somasagara, R.R., Hegde, M., Chiruvella, K.K., Musini, A., Choudhary, B. and Raghavan, S.C. (2012). Extracts of Strawberry Fruits Induce Intrinsic Pathway of Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells and Inhibits Tumor Progression in Mice. PLoS ONE, [online] 7(10), p.e47021.

Stoner, G.D., Wang, L.-S., Seguin, C., Rocha, C., Stoner, K., Chiu, S. and Kinghorn, A.D. (2010). Multiple Berry Types Prevent N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-Induced Esophageal Cancer in Rats. Pharmaceutical Research, [online] 27(6), pp.1138–1145.

Sut, S., Poloniato, G., Malagoli, M. and Dall’Acqua, S. (2018). Fragmentation of the main triterpene acids of apple by LC‐APCI‐MSn. Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 53(9), pp.882–892.

Torres‐Sánchez, L., López‐Carrillo, L., Malaquı́as López-Cervantes, Celina Magally Rueda-Neria and Wolff, M.S. (2000). Food Sources of Phytoestrogens and Breast Cancer Risk in Mexican Women. Nutrition and Cancer, 37(2), pp.134–139.

Tsiapara, A.V., Jaakkola, M., Chinou, I., Graikou, K., Tolonen, T., Virtanen, V. and Moutsatsou, P. (2009). Bioactivity of Greek honey extracts on breast cancer (MCF-7), prostate cancer (PC-3) and endometrial cancer (Ishikawa) cells: Profile analysis of extracts. Food Chemistry, 116(3), pp.702–708.

Vasconcelos, G.N., Sousa, H.G.S., Guerreiro, L.H.H., Ferreira, C.C., Castro, D.A.R. And Machado, N.T. (2018). Fractional Distillation Of Bio-Oil Produced By Pyrolysis Of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart) Seeds. Blucher Chemical Engineering Proceedings, pp.1360–1363. Doi:Https://Doi.Org/10.5151/Cobeq2018-Pt.0361.

Wawruszak, A., Halasa, M. and Karolina Okla (2021). Lycium barbarum (goji berry), human breast cancer, and antioxidant profile. Elsevier eBooks, pp.399–406.

Wellstein A. General principles in the pharmacotherapy of cancer. In: Brunton LL, ed. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. p. 1161-201.

Wen, C.T.P., Hussein, S.Z., Abdullah, S., Karim, N.A., Makpol, S. and Mohd Yusof, Y.A. (2012). Gelam and Nenas honeys inhibit proliferation of HT 29 colon cancer cells by inducing DNA damage and apoptosis while suppressing inflammation. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP, [online] 13(4), pp.1605–1610. doi:https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1605.

Williner, M.R., Pirovani, M.E. and Güemes, D.R. (2003). Ellagic acid content in strawberries of different cultivars and ripening stages. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 83(8), pp.842–845.

Wu, S., Liu, Y., Michalek, J.E., Mesa, R.A., Parma, D.L., Rodriguez, R., Mansour, A.M., Svatek, R., Tucker, T.C. and Ramirez, A.G. (2019). Carotenoid Intake and Circulating Carotenoids Are Inversely Associated with the Risk of Bladder Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-analysis. Advances in Nutrition, 11(3), pp.630–643.

Yaacob, N.S. and Ismail, N.F. (2014). Comparison of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of 4-hydroxytamoxifen in combination with Tualang honey in MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 14(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-106.

Yaacob, N.S., Nengsih, A. and Norazmi, M.N. (2013). Tualang Honey Promotes Apoptotic Cell Death Induced by Tamoxifen in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, [online] 2013, p.e989841. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/989841.

Yan, Y., Liu, N., Hou, N., Dong, L. and Li, J. (2017). Chlorogenic acid inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, [online] 46, pp.68–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.04.007.

Yang, K.-C., Chia Ti Tsai, Wang, Y., Po Li Wei, Lee, C.-F., Chen, J.-H., Wu, C. and Yuan Soon Ho (2009). Apple polyphenol phloretin potentiates the anticancer actions of paclitaxel through induction of apoptosis in human hep G2 cells. 48(5), pp.420–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.20480.

Zeng, A., Liang, X., Zhu, S., Liu, C., Wang, S., Zhang, Q., Zhao, J. and Song, L. (2020). Chlorogenic acid induces apoptosis, inhibits metastasis and improves antitumor immunity in breast cancer via the NF‑κB signaling pathway. Oncology Reports, 45(2), pp.717–727. doi:https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2020.7891.

Zielinska, D., Laparra-Llopis, J.M., Zielinski, H., Szawara-Nowak, D. and Giménez-Bastida, J.A. (2019). Role of Apple Phytochemicals, Phloretin and Phloridzin, in Modulating Processes Related to Intestinal Inflammation. Nutrients, 11(5), p.1173. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051173.

Leave a comment