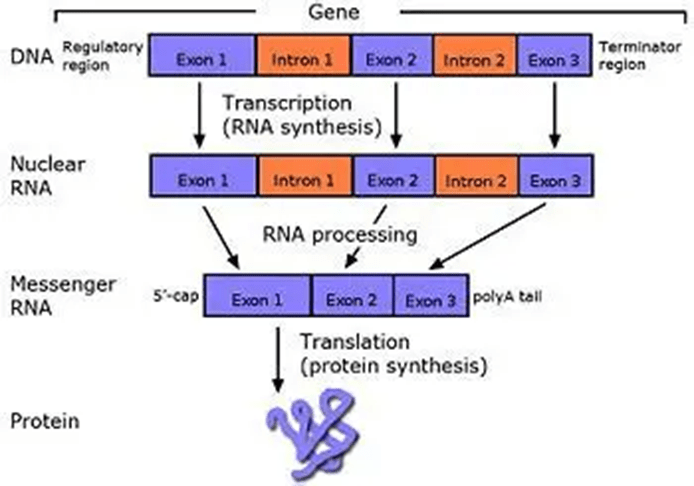

There is increasing evidence that reveals the role of the X-linked recessive disease, Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), in elevating the risk of cancer. To date, it has been implicated in the occurrence of brain cancer, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, benign enchondroma, leukaemia, lymphomas, melanomas, and carcinomas (Vita et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021). Upon exploring the causal link, there is variation in the tumourigenic response to the DMD gene products. For example, Dp71, a short dystrophin protein, is maintained in the cancer environment, whereas Dp427, which researchers suspect is a tumour suppressor, is inactivated in cancer due to a loss of 5’ exons (Jones et al., 2021). Exons are the coding regions that produce the protein, whereas introns are the non-coding regions – please see Figure 1. The coding regions join together, and the introns are removed. This facilitates ribosomes in protein synthesis.

Figure 1: The production of protein

About Dystrophin

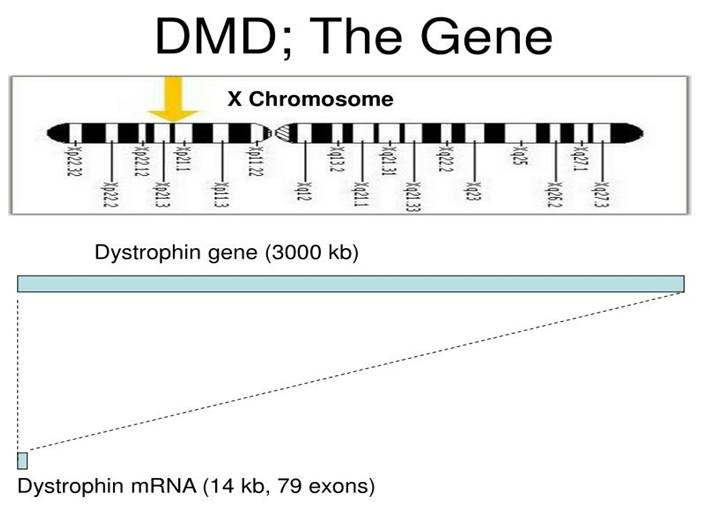

The molecular basis of DMD was explored in the 1980s, and the cloning of the gene involved in DMD is dystrophin. This led to the discovery of physiological consequences of DMD. The dystrophin gene has 206 million base pairs and 79 exons with promoter regions across 2.4 Mb (Jones et al., 2021). It represents 0.01% of the entire human genome (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). However, patients with DMD have a deletion of 45 exons on Xp. 21.

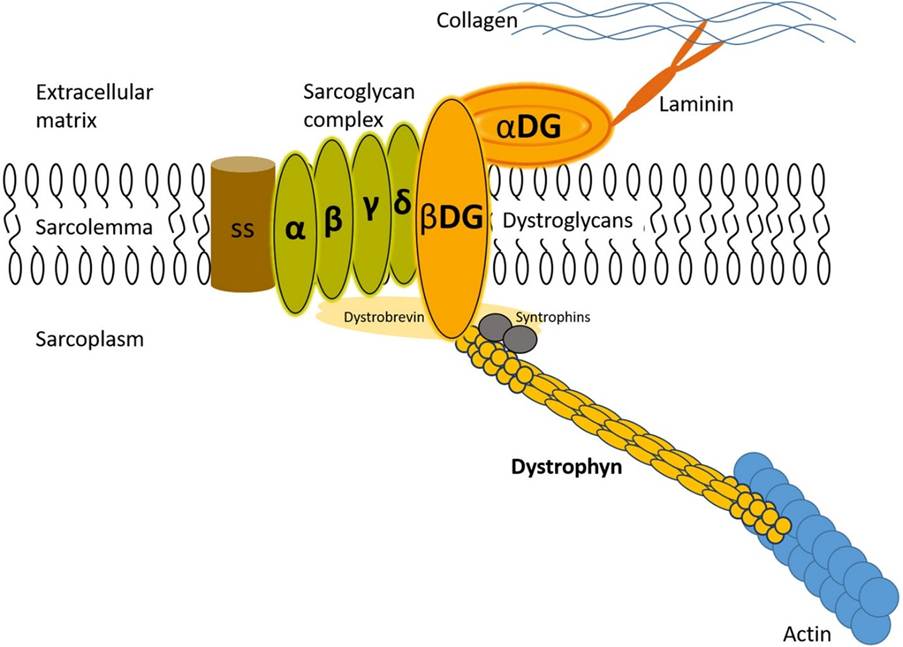

Under normal conditions, dystrophin is a rod-shaped cytoplasmic protein that aims to bind actin fibres in the cortex of muscle cells to extracellular basal lamina (connective tissue) – Please see Figure 2. The bridge formed between actin and transmembrane complex is called dystrophin-associated sarcoglycan complex (DASC) in the sarcoplasm. This facilitates contraction of the cardiac and skeletal muscles (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). In DMD, the DASC complex is formed without the dystrophin protein, causing imbalance.

Figure 2: The dystrophin-sarcoglycan complex that helps maintain the integrity, structure, and function of muscles. (Caris and Krajacic, 2017)

Several protein complexes facilitate the role of dystrophins, namely: dystroglycans, dystrobrevins, syntrophins, sarcoglycan-sarcospan. Dystroglycan complex is a membrane-spanning complex composed of two subunits, alpha- and beta-dystroglycan. Alpha-dystroglycan is a cell surface peripheral membrane protein which binds to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Beta-dystroglycan is an integral membrane protein which anchors alpha-dystroglycan to the cell membrane. The dystroglycan complex strengthened the link between ECM and the cellular membrane.

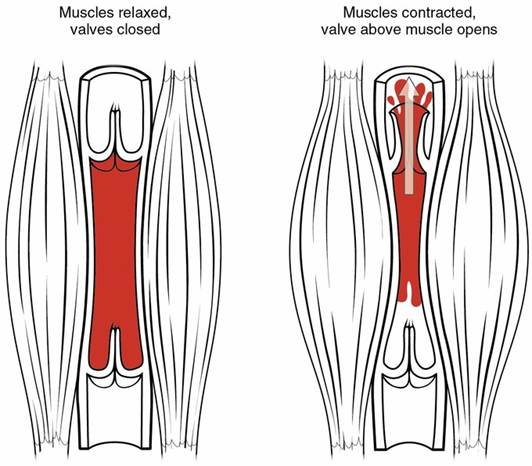

The several isoforms of dystrobrevins and syntrophins are integral to binding to dystrophin. Alpha dystrobrevin is localized in the sarcolemma of the skeletal muscle. Beta dystrobrevin also has a prominent role. Similarly, the three isoforms of syntrophin are expressed in the skeletal muscle. Syntrophin shows interaction with both dystrophin and dystrobrevin. Additional roles include mediating the nitric neuroloxide synthesis (nNOS). nNOS increases vasodilation, dilating the blood vessels near the muscle tissue – please see Figure 3. This increases the rate of blood flow to facilitate muscular contraction. There is a direct relationship between syntrophin and nNOS. Low levels of syntrophin would lower the production of nNOS. Sarcoglycan-sarcospan complex strongly interacts with dystrophin.

Under pathological conditions, there is no evidence of the functional role of mutated dystroglycans in DMD patients and experimental models. In contrast, rodent models have shown mild dystrophy with mutated dystrobrevins and syntrophin, but no mutations were found in human DMD subjects. Nevertheless, patients with DMD have shown significant decrease or loss of the sarcoglycan-sarcoplasm. Other types of proteins involved are caveolac, where there is an abnormal size and number. This is found in all muscle types and interacts with the C-terminal.

Figure 3: Blood flow during the skeletal muscle contraction

About X-linked recessive sex disorder

DMD is a rare X-linked recessive disorder caused by deletions and mutations (changes) of the dystrophin gene. The mutated gene is inherited from parents or can independently occur in the progeny despite the parents having no DMD (National Health Service, 2025). This leads to variation in the expression of the functional protein (0 to 5% of normal levels or a complete absence of the dystrophin protein (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). According to Sarepta Therapeutics (2023), 72% have large deletions, 7% have large duplications, and the remainder have small changes (20%).

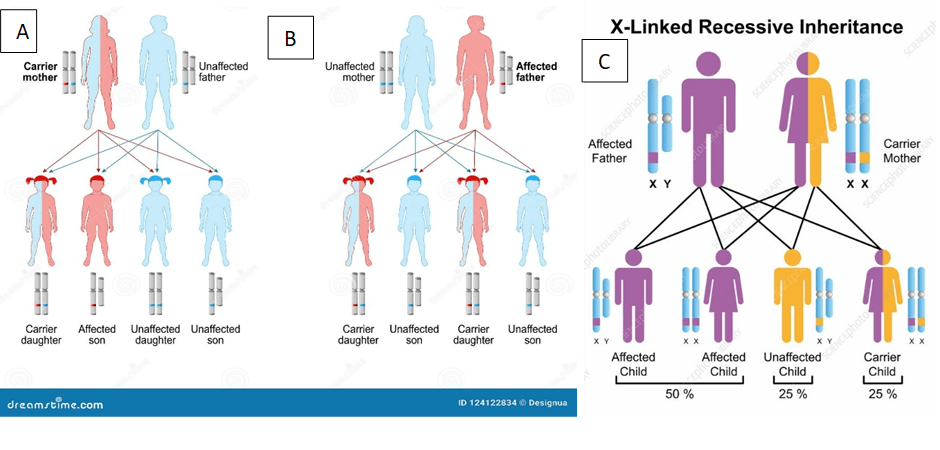

Males have one X and Y chromosome (XY) whereas females have two X chromosomes. Chromosomes are long thread-like structures of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). A sex-linked disorder originates from a change in a gene (mutation) on the X chromosome. A gene is a short section of DNA. As males have one copy of the gene on the X chromosome, they are affected if the dystrophin gene is mutated. On the other hand, females are less likely to develop DMD; if one X chromosome is affected, the other X chromosome serves as a protective measure and compensates for the damaged chromosome. Symptoms are less severe (NHS Inform, 2024).

A pedigree analysis is a way of presenting the likely outcomes of a genetic disorder. There is a 25% chance of having a child with DMD and a 25% chance of having a child that is a carrier; one X chromosome has a mutated dystrophin. This occurs if the mother is a carrier and the father does not have the mutated dystrophin gene. Please see Figure 4A. However, this percentage chance decreases if the father is affected and the mother is unaffected, where the two X chromosomes have a normal dystrophin gene. There is a 50% chance of having two children that are carriers – please see Figure 4 B. On the other hand, if the father is affected and the mother is a carrier, there is a two-fold increase (50% chance) of having two children with DMD – please see Figure 4C.

Figure 4: Pedigree analysis of the different outcomes of DMD. A) Carrier mother and unaffected father B) Unaffected mother and affected father. C) Affected father and carrier mother.

About DMD

The different forms of muscular dystrophy are illustrated in Figure 5. The most common and most severe form of dystrophinopathy is DMD. It is estimated that one in 3600 to 6000 live male births has DMD (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). It mainly affects boys and the clinical symptoms manifest between 2 and 3 years, where they experience weakness in their voluntary muscles – please see Figure 6 (National Health Service, 2025). Symptoms rapidly progress and by the age of 12, they are wheelchair-bound because they are unable to walk, and without active medical intervention, the mean age of death is 19 years (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). Therefore, patients with DMD have a short life expectancy.

However, most people with DMD progress to adulthood but commonly die from cardiac (heart) or respiratory (breathing) failure during their 30s (NHS Inform, 2024). However, the most common cause is cardiac failure (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). Other symptoms experienced by patients with DMD are mainly associated with mobility, speech, and behaviour. For example, muscle pain, tight joints, difficulty walking, running, getting up, and lifting. Some patients have a waddling gait where they tend to walk on their toes and have an arched lower back (National Health Service, 2025). Increased risk of falling, late development in speech, learning, and behavioural difficulties are other symptoms (National Health Service, 2025).

Figure 5: Types of Muscular Dystrophy

Figure 6: Types of muscles affected DMD

The Methods of Detection of DMD

There is a discrepancy between the estimated lifespan of a treated DMD patient and a DMD patient who was not. If early medical intervention is used, the lifespan will increase twofold and depends on two time factors. The time taken for the caregiver and undergo clinical evaluation is a mean time of 12 months. This is referred to as presentation delay. The other factor is the time taken between presenting to a healthcare professional and screening for the enzyme creatine kinase. This form of delay is referred to as diagnostic delay (Caris and Krajacic, 2017).

Creatine kinase is a sensitive and vital marker for skeletal muscle damage besides the enzyme aminotransferase. The levels of CK are estimated to be a minimum of 15-fold higher than normal levels, especially in patients aged 3. It can potentially increase the lifespan if detected early (Caris and Krajacic, 2017). Skeletal muscular damage is assessed by inserting a small needle to measure the electrical activity. This is called electromyogram (National Health Service, 2025).

Genetic tests to determine the mutational status of dystrophin are essential. This commonly requires a sample of blood or saliva from the patient (Sarepta Therapeutics, 2023). Some patients require a standardized genetic test that can detect mutations in the dystrophin gene with a 95% success rate. Conversely, other patients (5%) require multiple comprehensive genetic tests to identify the mutation. This may require approximately three weeks (Sarepta Therapeutics, 2023). Determining whether the dystrophin gene is inherited and possible carriers are also explored.

There are various strategies that can identify and isolate genes involved in this monogenic disorder. Cytogenetic rearrangement results in DMD having a sub-chromosomal location to Xp21 – Please see Figure 7. Xp21 fusion with 285 ribosomal RNA nucleus on chromosome 21, allowing marker XJ1.1 à closely linked to be isolated.

Figure 7: The genetic characteristic of the dystrophin gene.

A second technique is to use DNA from a boy called ‘BB’ who suffered from three X-linked disorders: DMD, chronic granulomatous disease, retinitis pigmentosa. Genes responsible for these disorders are closely linked (Francke et al., 1985; Kniffin, 2024; Brown et al., 1996). It appears that BB’s X chromosome cytogenetically carried a visible deletion that affected part of all three genes. A hemizygous interstitial deletion of part of chromosome Xp21 was presented. DNA by this deletion isolated from XXXXY cell line using subtractive hybridization techniques. One of these clones, pERT87, is closely linked to DMD mutation sites. pERT87 and XJ1.1 clones used to map locus, constructing long-range restriction map. pERT used to probe cDNA libraries, resulting in isolation of cDNA clones spanning 14-kb mRNA of locus. Biopsy and MRI scan of muscles can also support the diagnosis (National Health Service, 2025).

The link between DMD and HNSCC

Jones et al. (2025) analysed The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data to determine the link between DMD and Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). Patients with high expression of DMD, particularly with the dystrophin gene product Dp71ab, had elevated overall survival and progression-free survival. Immunohistochemical analysis of HNSCC tissues discovered the expression of dystrophin protein in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Jones et al., 2020). This potentially explains why Dp71 can suppress cell proliferation and disrupt nuclear morphology, leading to positive clinical outcomes. There were 388 genes upregulated in the differential gene expression analysis. The pathways were associated with the biogenesis of ribosomes, muscle processes, and regulation of non-coding RNA (intron) (Jones et al., 2025). The medial survival difference for Dp71ab was 42 months. HNSCC patients with positive human papillomavirus (HPV) but low expression of DMD had poor survival rates. This highlights Dp71 as a potential biomarker for prognosis and therapy, but further studies are needed.

References

Brown, J., Dry, K.L., Edgar, A.J., Pryde, F.E., Hardwick, L.J., Aldred, M.A., Lester, D.H., Boyle, S., Kaplan, J., Jean-Louis Dufier, Ho, M.-F., Monaco, A.M., Musarella, M.A. and Wright, A.F. (1996). Analysis of Three Deletion Breakpoints in Xp21.1 and the Further Localization of RP3. Genomics, 37(2), pp.200–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/geno.1996.0543.

Caris, C. and Krajacic, P. (2017) Bridging the Gap: An Osteopathic Primary Care–Centered Approach to Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 117(6), pp.377-385

Francke, U., Ochs, H. D., de Martinville, B., Giacalone, J., Lindgren, V., Disteche, C., Pagon, R. A., Hofker, M. H., van Ommen, G.-J. B., Pearson, P. L., Wedgwood, R. J. Minor Xp21 chromosome deletion in a male associated with expression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, chronic granulomatous disease, retinitis pigmentosa, and McLeod syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 37: 250-267, 1985.[PubMed: 4039107]

Gian Luca Vita, Politano, L., Berardinelli, A. and Vita, G. (2021). Have Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patients an Increased Cancer Risk? Journal of neuromuscular diseases, 8(6), pp.1063–1067. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-210676.

Jones, L., Divakar, S., Collins, L., Hamarneh, W. Ameerally, P., Anthony, K. and Machado, L. (2025). Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene product expression is associated with survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Scientific Reports, [online] 15(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94221-9.

Jones, L., Naidoo, M., Machado, L.R. and Anthony, K. (2020). The Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene and cancer. Cellular Oncology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-020-00572-y.

Kniffin, C. (2024) McLeod Syndrome. Available at: https://www.omim.org/entry/300842 (Accessed: 23rd July 2025)

Machado, L.J., Anthony, K., Jones, L., Divakar, S., Collins, L., Hamarneh, W. and Ameerally, P. (2025) Association between Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene products and prognosis in head and neck cancer. Available at: https://www.esmoopen.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2059-7029%2825%2900213-3 (Accessed: 23rd July 2025)

National Health Service (2025) Muscular dystrophy Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/muscular-dystrophy/ (Accessed: 23rd July 2025)

NHS Inform (2024) Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/brain-nerves-and-spinal-cord/muscular-dystrophy/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-dmd (Accessed: 23rd July 2025)

Sarepta Therapeutics (2023) A guide to genetic testing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Available at: https://www.duchenne.com/sites/default/files/2023-05/A_Guide_To_Genetic_Testing_In_DMD.pdf (Accessed: 23rd July 2025).

Leave a comment