Part One: Raising Awareness On Heart Disease

Original post by Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas on 11th March 2015

Updated article by Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas on 2nd August 2025

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) arise from a pathological balance of genetic, behavioural, physiological, and environmental factors. The World Health Organisation (2024) announced there were 43 million people who died in 2021 from NCDs. Most of the deaths are associated with cardiovascular disease, where 19 million people died in 2021. In descending order, cancer (10 million), chronic respiratory diseases (4 million), and diabetes (2 million).

NCDs are not caused by contact with pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and fungi. The most common risks of NCD are poor diet, physical inactivity, air pollution, and alcohol. However, it is important to state that not all bacteria and fungi cause disease. Some bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus, are used to produce cheese and yogurt. Fungi like yeast can make bread and pastries, whilst other fungi like mushrooms are also edible.

Another misconception is the relationship between age and NCDs. Despite the strength of the immune system and the ability to undergo wound healing deteriorating with age, this increases the likelihood of infections and NCD in the elderly. Did you know that 18 million deaths associated with NCD occurred before the age of 70? 82% of these premature deaths were from low and middle-income countries. This suggests that everyone is at risk of NCD and is more associated with lifestyle factors, poverty, and being socially disadvantaged in accessing health services.

To decrease the extent of inequities, the World Health Organisation, as part of its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, aims to lower deaths by a third for patients aged 30 to 70 years. This is achieved by focusing on the modifiable risk factors through awareness. Efficient interventions and improving care management through detecting, screening, treatment, and palliative care at all levels of healthcare services: primary, secondary, and tertiary care.

This article aims to provide an understanding of the heart’s structure, how the heart functions under normal and diseased states, and how to overcome heart disease. This article is part of a series of health awareness of NCDs; the other NCDs are respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer. There is a separate section dedicated to cancer in our health projects.

The Function Of The Cardiovascular System

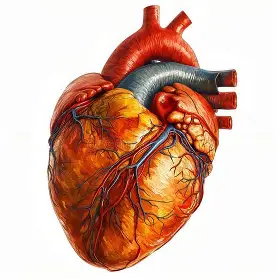

Can you hear your heart beating? The heart is a muscular organ that is the size of a fist. It approximately beats 100,000 times a day and is situated in the centre of the chest, tilted slightly towards the left. It is estimated that ca. 5 litres of blood are pumped around the body through a network of tubes called blood vessels. However, this varies by sex; males have four to six litres of blood, whereas females have four to five litres, which is 8% of total body mass (Aberystwyth University, n.d).

The blood vessels form the circulatory system, which transports substances (British Heart Foundation, 2024). Key examples are glucose (sugar) and oxygen to reach the cells and tissues to provide energy via a process called respiration. The energy is found in the food we eat and stored in the body for when needed. Amino acids are the building blocks that form proteins for growth and repair. Fats, otherwise known as lipids, serve to provide warmth and insulation. Hormones regulate bodily functions. Antibodies are proteins that protect the body from infection and disease. The blood also removes waste such as carbon dioxide and urea (Aberswyth University, n.d.; Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

There are two forms of circulation: systemic and pulmonary. Blood travelling around the body is referred as systemic whereas, pulmonary involves the heart and lungs.

The Structure And Function Of The Heart

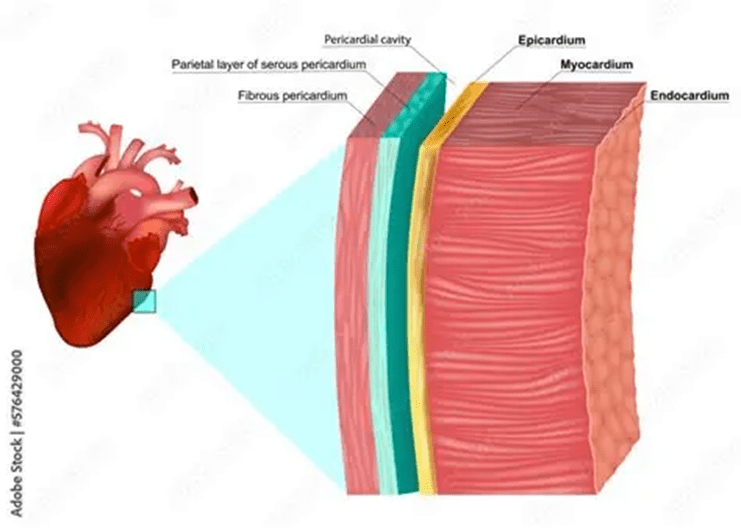

The heart consists of three layers of muscular tissue from the outer to the inner layer: pericardium, myocardium, and endocardium – please see Figure 1. The pericardium is a thin outer lining of connective tissue that protects the heart and anchors it in position (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberyswyth, n.d.). It consists of two layers separated by pericardial fluid to help decrease friction between heartbeats. The epicardium is next to the myocardium (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006). Myocardium is a thick muscular layer that contracts (squeezes) and relaxes while pumping blood. It produces the heartbeat. The endocardium is a thin inner layer that lines the four chambers of the heart (British Heart Foundation, 2024).

Figure 1: Layers of the heart.

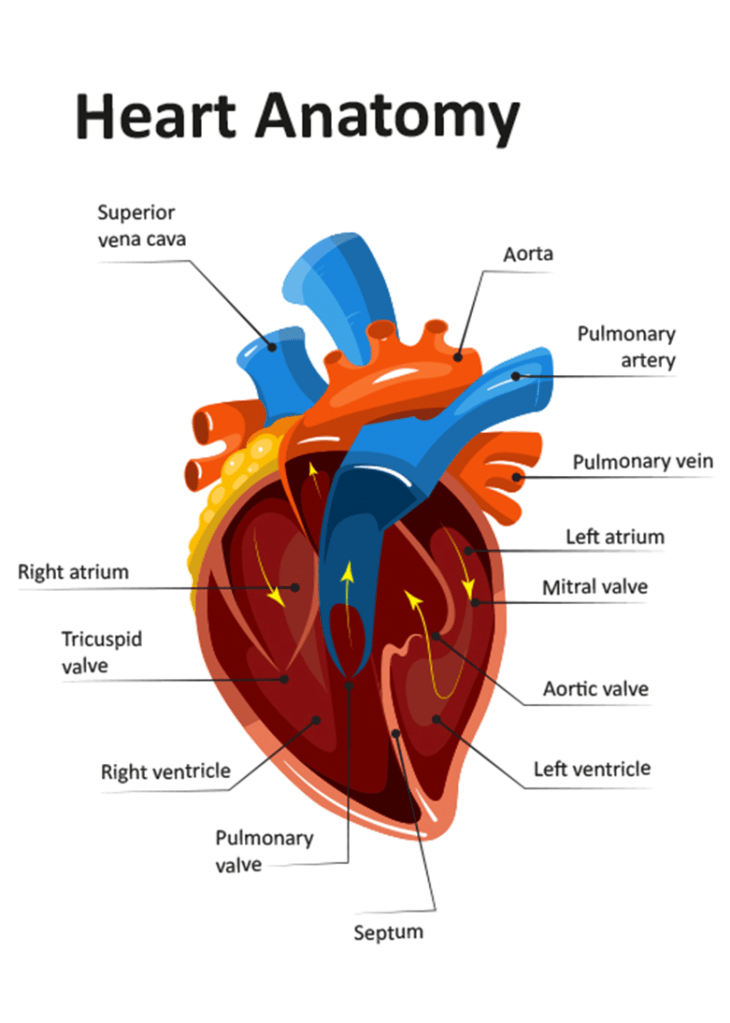

The heart is divided into two sections: left and right, separated by a thin muscular wall called a septum – please see Figure 2. Each side has an upper and lower chamber. The upper chamber is the atrium (atria for plural), who receive blood into the heart. The lower chamber is the ventricle that pumps blood out of the heart (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d.).

There are four main blood vessels in the heart: the aorta, the pulmonary artery, the pulmonary vein, and the vena cava. Pulmonary refers to their association with the lungs. At first, blood containing low levels of oxygen (deoxygenated blood) and high levels of carbon dioxide from the body tissues and organs returns to the heart via large veins called the vena cava. This is because it has delivered all the oxygen to the target tissues and collected carbon dioxide. There are two vena cavae: the inferior vena cava returns oxygen-depleted blood back to the heart from the lower part of the body below the diaphragm, whereas the superior vena cava is from the upper part of the body. The pulmonary artery sends the deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs, where gas exchange takes place. This helps increase the levels of oxygen in the blood and remove carbon dioxide. The pulmonary vein receives blood with high levels of oxygen (oxygenated blood) from the lungs and returns it to the heart. This is the only vein that carries oxygenated blood; the other veins around the body carry deoxygenated blood. The aorta is a large artery that transports oxygenated blood at high pressure from the heart to the body.

The blood travels around the body in one direction and is controlled by flaps of tissue called heart valves, otherwise known as cusps. They open and close with each heartbeat, preventing backflow (British Heart Foundation, 2024). On the right side of the heart, there are the tricuspid and pulmonary valves – please see Figure 2. The tricuspid valve is situated between the right atrium and ventricle, where it prevents backflow into the right atrium when the ventricle contracts. This is why it is also referred to as the right atrioventricular valve. It has three cusps in its structure. The pulmonary valve is between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. It prevents backflow of the blood into the right ventricle after going to the lungs to gain oxygen (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d).

On the left side of the heart, the mitral or bicuspid valve is between the left atrium and ventricle. It is also known as the left atrioventricular valve. It has two cusps in its structure and helps prevent backflow into the left atrium when the left ventricle contracts. The muscular wall on the left side of the heart is much thicker than the right side because of the difference in oxygen concentration flowing through their respective blood vessels. The aortic valve is between the left ventricle and the aorta; it prevents backflow of blood to the left ventricle after it goes to the aorta (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d).

Figure 2 Structure of the heart

The Structure And Function Of The Blood Vessels

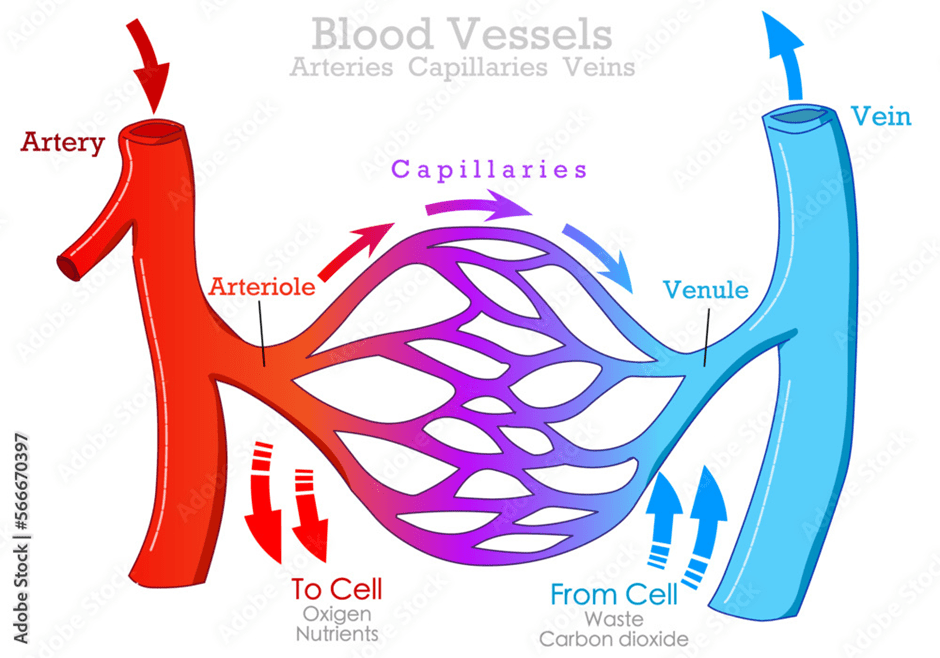

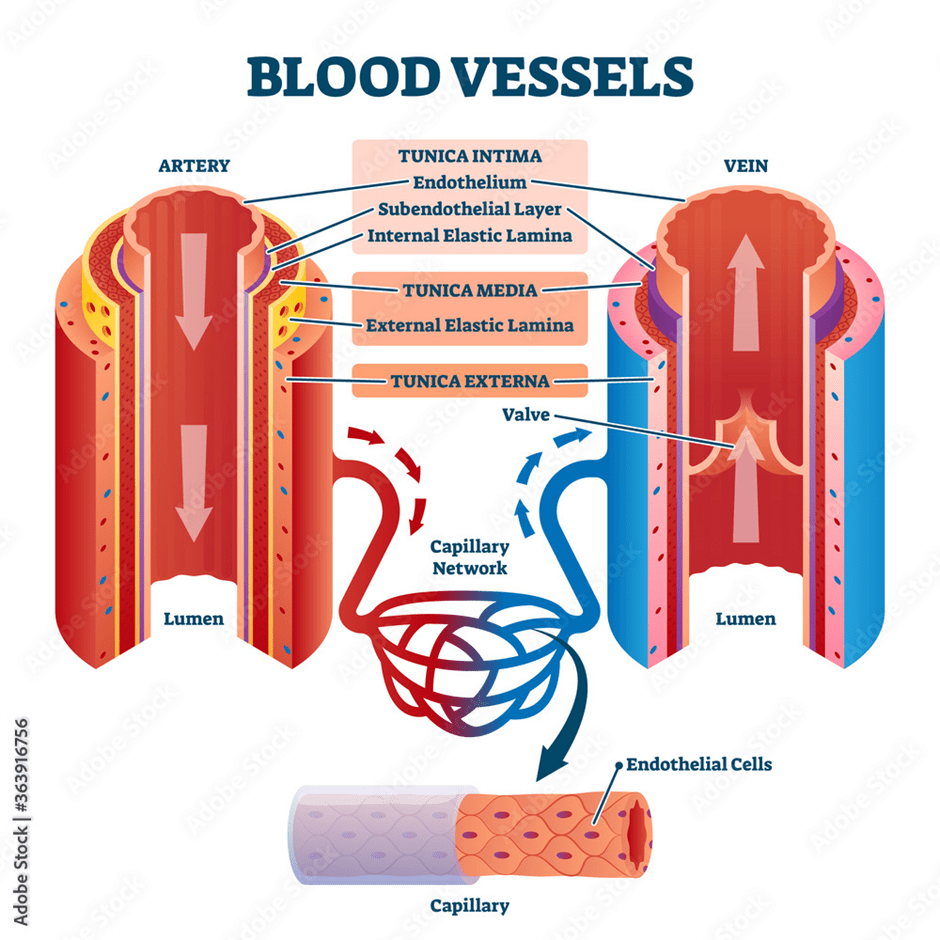

The network of tubes that transports blood around the body consists of three main blood vessels and two sub-vascular vessels that are characteristically adapted for their function. The centre of the blood vessel is referred to as the lumen – Please see Figure 3. The arteries carry blood with high levels of oxygen and have thicker, muscular elastic tissue that allows them to carry blood at high pressure. This provides a reason for their smaller lumen and lack of valves (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006). The arteries relax to increase their diameter when the blood pressure needs to rise. However, when less blood is required, they contract to decrease their diameter. This highlights the range of adaptations arteries have to perform their function. Arteries are divided into smaller arteries called arterioles to facilitate blood flow and pressure (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d.).

Figure 3: The main blood vessels

The three main layers found in the arteries are: tunica adventitia, tunica media, and tunica intima. The tunica adventitia is the outermost layer that protects and anchors the surrounding tissue. The tunica media has a high content of smooth muscle, and it is where the redistribution of blood flow takes place. The innermost layer is the tunica intima. It has direct contact with the blood, hence its smooth surface to help the flow of blood easily. Please see Figure 4 (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d).

Veins carry blood with low levels of oxygen towards the heart. Amongst its several adaptations are: a thin smooth muscle layer and the presence of valves. This helps to carry blood at low pressure with minimal driving force to push blood. This is with the exception of the pulmonary vein that carries oxygenated blood from the lungs to the heart. Veins are divided into smaller veins called venules (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d.).

Capillaries neither have a tunica adventitia nor a tunica media. They are one-cell thick, to help them diffuse oxygen carried by red blood cells, glucose (sugar) into target tissues, and remove carbon dioxide from cells and tissues. They are situated between arteries and veins, as shown in Figure 3. They can join venules and arterioles (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d.).

Figure 4: The layers found in each of the blood vessels

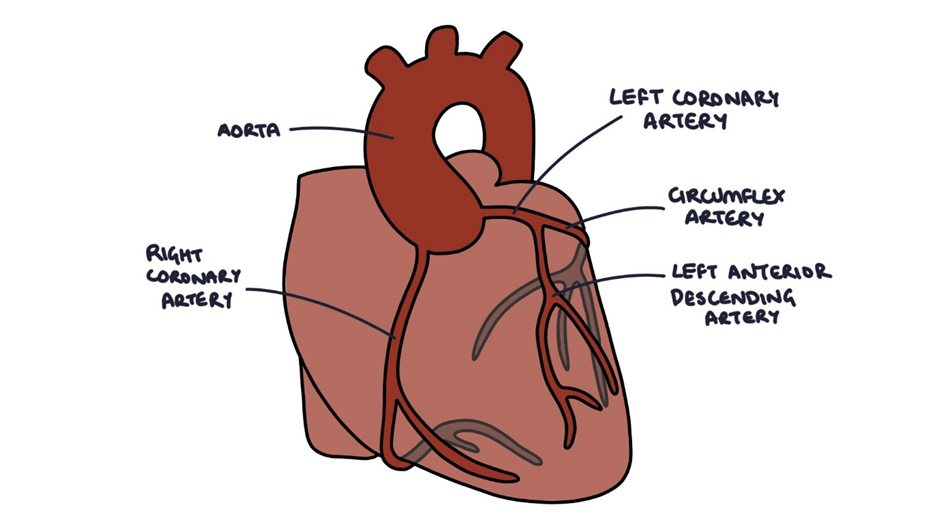

The heart has its blood supply to maintain its energy expenditure. It is implemented by the coronary arteries that provide the heart with oxygenated blood. They are branched off the aorta (British Heart Foundation, 2024; Aberswyth, n.d.). Please see Figure 5.

Figure 5: The presence of the coronay arteries that supply the heart muscle layer myocardium

Animals Have Different Heart Structures

It is interesting to observe the heart beyond human nature and to explore whether there is a similar or opposing structure in different animal species. Animals are divided into invertebrates and vertebrates. Invertebrates do not have a backbone. A prominent example of invertebrates is insects. Insects hold a dual status as the most abundant and diverse species on Earth, which shapes the natural settings around us, called ecosystems.

Most insects, like the bee, have a simple tube that stretches from the head to the abdomen (stomach) called the dorsal aorta or vessel – please see Figure 6. It is the only closed organ that functions like a heart and forms part of an open circulatory system (Romero, 2024). The heart is found in the abdomen and pumps haemolymph. Haemolymph is a fluid found in most insects that is neither blood nor contains red blood cells, and in turn cannot transport oxygen. It transports nutrients, for instance, amino acids and hormones, around the body through valves and small openings on the sides called ostia. Haemolymph also has a role in metamorphosis, wound healing, and immune responses (Alibhai et al., 2020; Romero, 2024). Metamorphosis is the transformation from an immature to a mature state. The aorta carries lymph from the thorax to the head (Romero, 2024).

Other insects, like the spider, have a dorsal vessel in the body near the intestines. In contrast, cockroaches have 13 heart chambers. Please see Figure 6 (Alibhai et al., 2020). This suggests there is variation in the structure of the heart in insects.

Figure 6: The anatomy of insects. a) The anatomy of the bee. b) A closer view of the heart system of the bee c) A closer view of the heart system of cockroaches d) The anatomy of a spider.

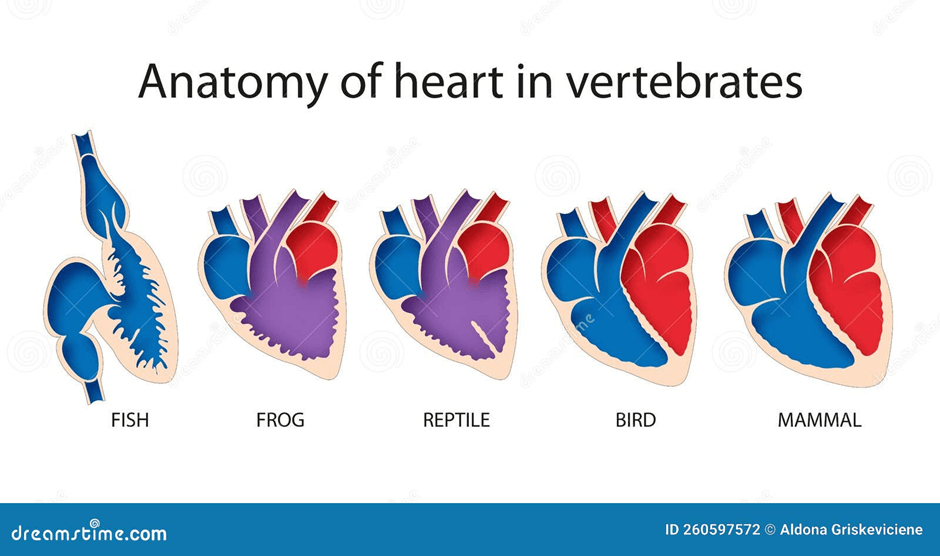

Vertebrates are animals with a backbone. They have a closed circulatory system and are composed of warm-blooded and cold-blooded animals. Birds and mammals are warm-blooded, whereas fish, amphibians, and reptiles are cold-blooded. Birds and mammals commonly have four heart chambers. Please see Figure 7. They both breathe through their lungs. However, birds have feathers, lay hard eggs on land, whilst mammals have hair, give live birth, and feed their young with milk.

Figure 7: The structure of the heart in vertebrates

Fish lay their eggs, or give live birth in water. They have gills, scales, and fins. Some aquatic animals, for instance, squids and octopuses found in the sea and oceans, are classified as cephalopods. Cephalopods are characterised by their symmetrical bodies, tentacles, and prominent heads (Alibhai et al., 2020). They have three hearts: the two branchial hearts pump to the gills and receive oxygen, and the third or systemic heart pumps oxygenated blood around the body (Alibhai et al., 2020). Please see Figure 8. This fuels the eight tentacles of the octopus and the suckers present on their arms. Other water species manage with minimal to no blood circulation, like the Starfish, jellyfish, and corals. Hence, a heart is not needed. Along their tract, the presence of cilia pushes seawater through bodies to gain access to oxygen (Alibhai et al., 2020).

Figure 8: The anatomy of an octopus

Amphibians are cold-blooded animals. Some breathe through gills, whilst others breathe through lungs. They lay jelly-like eggs in water and can live on both land and water. Some amphibians gain oxygen via their thin, moist skin. Other amphibians breathe via their lungs. They also differentiate in the structure of their heart: A frog has two atria and one ventricle with a septum – please see Figure 8. However, salamanders do not have a septum in the heart, nor do they have lungs.

Reptiles are cold-blooded animals with scaly skin and breathe through lungs. They lay leathery eggs on land or undergo live birth. A crocodile has a four-chambered heart with a hole in the chamber wall. This raises the question of whether it has a four-chambered wall like humans or a three-chambered wall like most reptiles and amphibians (Alibhai et al. 2020). Please see Figure 9. Low-oxygenated blood enters the heart from the body. It is then transferred to the lungs to gain oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood enters from the lungs and then travels to the body. There is partial mixing of blood in the heart, but to a lesser extent than that which occurs in the amphibians.

Figure 9: The structure of the heart in a crocodile.

How Does The Heart Pump Blood Around The Body?

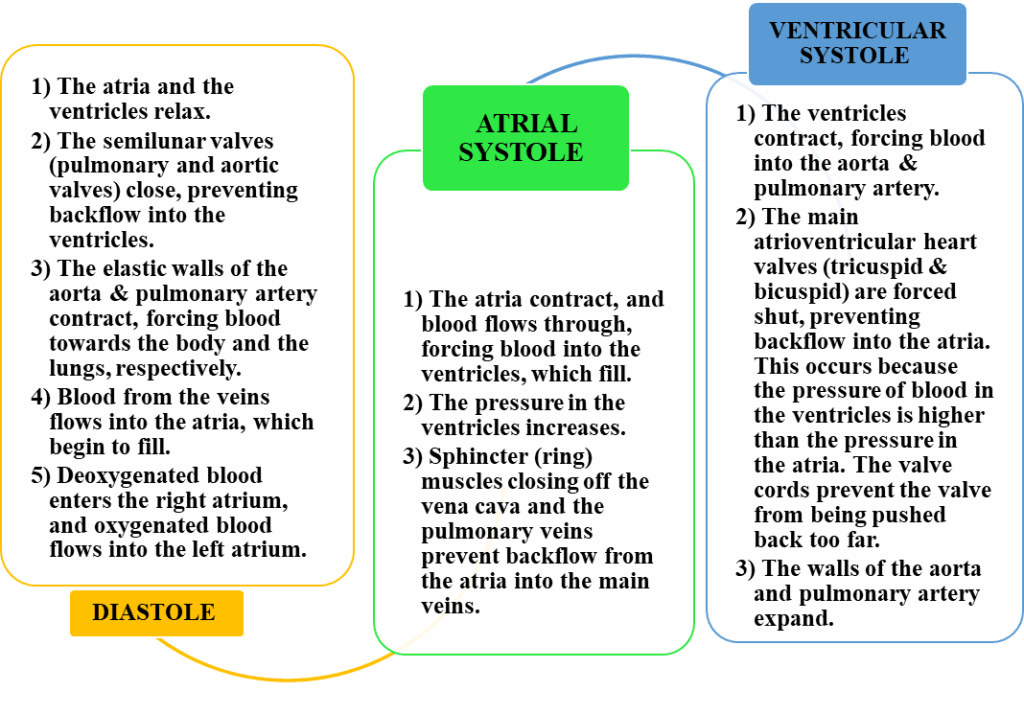

The heart is two pumps adhered together. Each pump has two chambers. When the right atrium contracts, the same happens to the left-hand side. The same is true when the right ventricle contracts. The blood must flow through the heart in one direction. Blood enters the atria from the veins and is then forced into the ventricles. The ventricles force the blood into the arteries. There are several sphincter muscles and valves that prevent blood from flowing the wrong way and act like parachutes. When blood flows the wrong way, the valves bulge out, blocking the path. There are three distinctive stages in a heartbeat: diastole (relaxation), atrial systole (contraction of the atria), and ventricular systole (contraction of the ventricles). Please see Figures 10 and 11 presented as a flow diagram and image, respectively.

Figure 10: A flow diagram presenting the steps involved in a heartbeat.

Figure 11: An illustration of the steps involved in a heartbeat

The first heart sound is ‘lub’ when placing the stethoscope on the patient’s chest. It represents the shutting of the atrioventricular valves. The second ‘Dub’ sound is the closure of the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonary valves) when the ventricles relax. Please see Figure 12.

Figure 12: The distinction between the heart sounds. S1 represents ‘Lub’ whilst S2 represents ‘Dub’.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is the pressure required to push the blood out of the heart and into the arteries. The normal blood pressure is 120/80 mmHg.

120 is related to the systolic pressure that occurs at the artery wall when the heart contracts.

80 refers to the diastolic pressure when the heart relaxes and refills with blood.

These values occur only in the artery present in the upper arm (brachial artery).

However, the closer the pressure measured towards the heart, the higher it is. The venous pressure (pressure in the veins) is estimated to be less than 20 mmHg (Aberyswyth University, n.d.).

Conduction System

Moreover, the cardiac muscle (myocardium) is coordinated by the electrical conduction system to help the heart pump efficiently. It is under involuntary control and will continue to beat even if all nerves are disconnected. This is different in other muscles, for instance, the skeletal muscle that is innervated by a nerve (Aberyswyth University, n.d.). The conduction system consists of specialised cells called Autorhythmic cells and has a specific rhythm that sets the pace of the heartbeat.

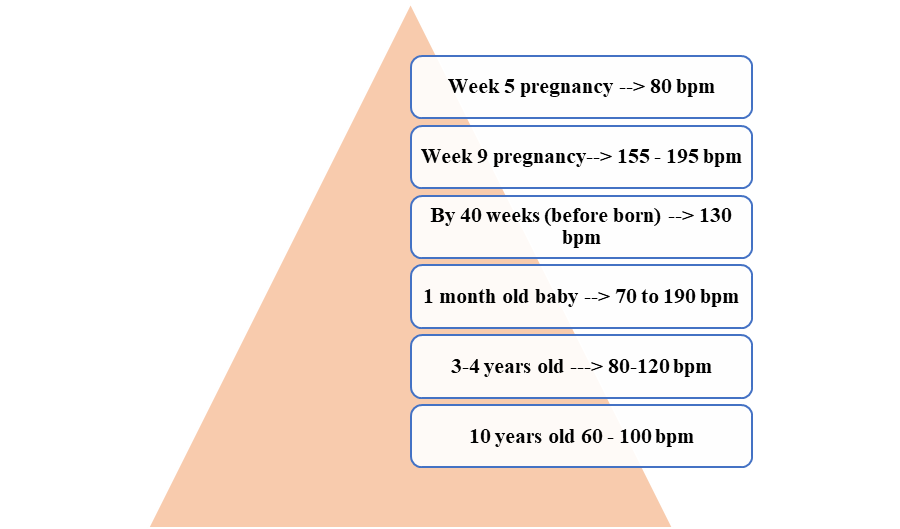

The heart rate is the rhythm at which the heart beats. Under normal circumstances, the fastest rhythm is in the sinoatrial (SA) node in the top right atrium. It is estimated that every 0.6 seconds, a heart rate of 100 bpm (beats per minute) occurs. However, the rhythm decreased to 75 bpm due to the nerves connected to the heart; this is the resting heart rate. The heart rate for an adult is in the range of 60 to 100 bpm. This varies with age according to the British Heart Foundation (2024). Please see Figure 13.

Figure 13: The Heart Rate Of Different Age Groups

To excite the heart, the SA node sends an electrical signal to the atria (top chambers), causing them to contract and allowing blood into the ventricles. On the contrary, the electrical signal cannot travel into the ventricles; instead, it is transmitted to the atrioventricular node (AV node), which goes through the septum, the Bundle of His branches, to the bottom of the heart called the apex. At the apex, the branches divide into the left and right Purkinje fibres that carry the impulse into the myocardium (heart muscle) to initiate the ventricular contraction. Please see Figure 14.

Figure 14: The heart conduction system

Electrocardiography

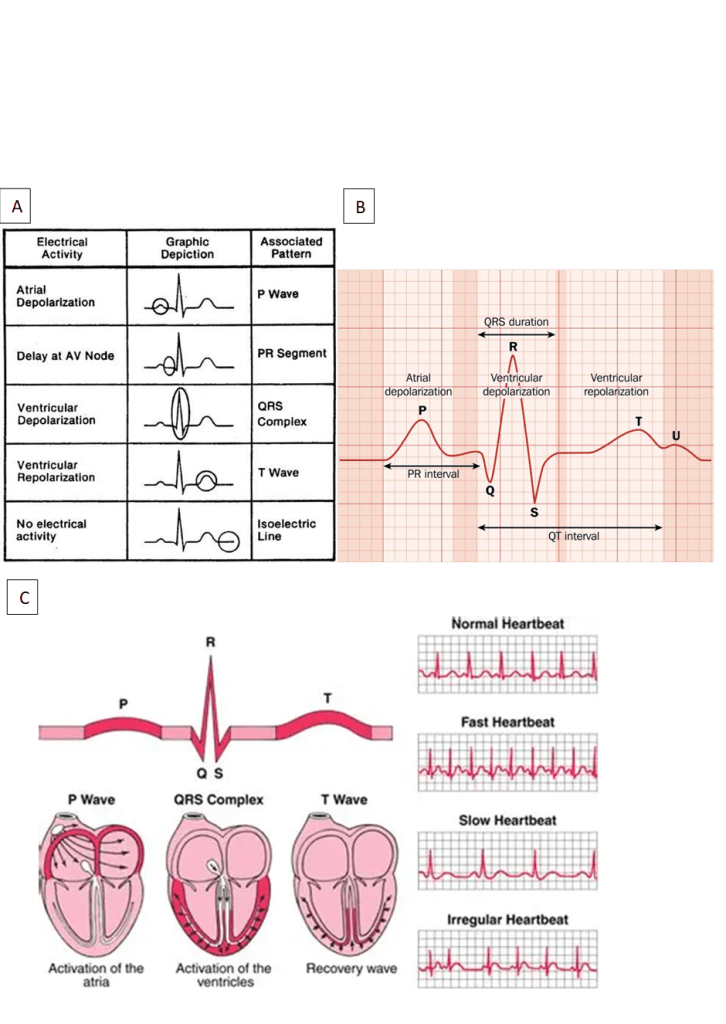

Electrocardiography (ECG) is an instrument that measures the electrical activity of the heart and changes in the heartbeat. The ECG pattern consists of three waves: the P, QRS, and T wave. The P wave represents the SA node, which initiates the heartbeat by sending a signal to the atria as the natural pacemaker. This is atrial depolarization. A short pause occurs when travelling down the AV bundle until the Purkinje fibers. This is the PR segment. The QRS complex is the contraction of the ventricles (ventricular depolarisation). The reset of the ventricles is the T wave. This is called ventricular repolarisation. Please see Figure 15.

Figure 15: A graphical representation of the Heartbeat. a) Label of different parts of the heart beat. b) ECG trace c) A visual presentation of the normal and irregular heartbeats. This will be discussed later in the article.

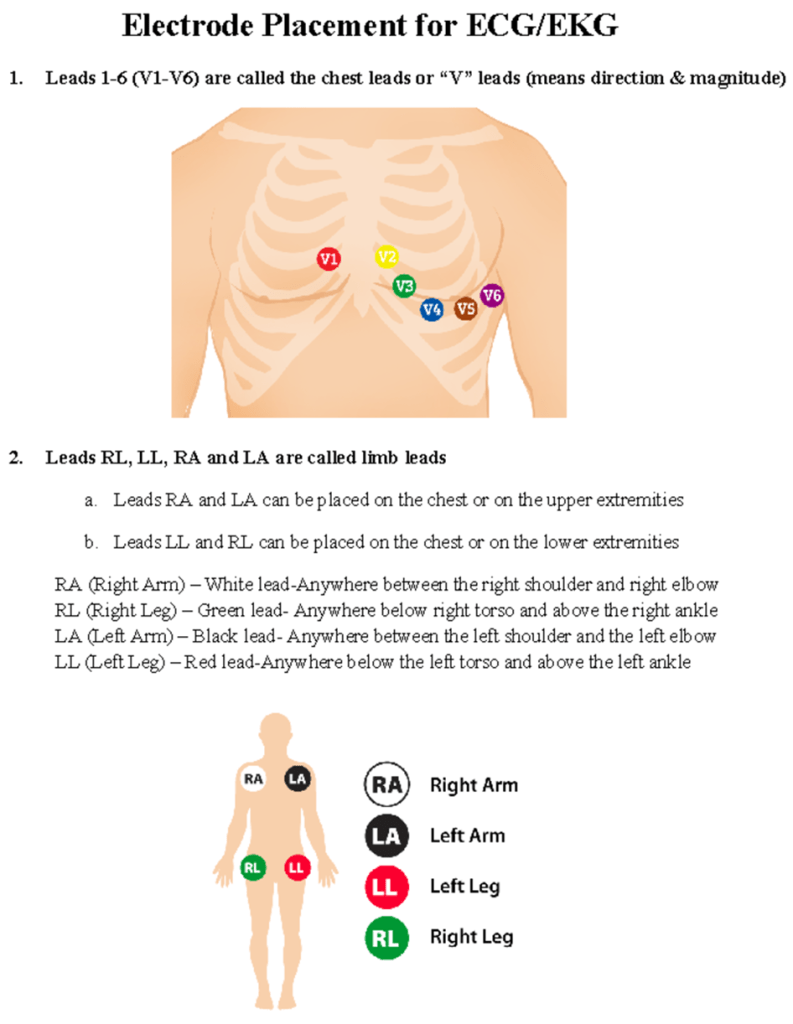

A standard ECG has 12 leads, as presented in Figure 16. There are 6 chest leads (V1 to V6) that monitor the heart from a horizontal perspective.

V1 and V2 right ventricle.

V3 and V4 intraventricular septum. V4 presents the mid-clavicular line

V5 and V6 left ventricle. V5 presents the anterior axillary line, and V6 is the mid axillary line.

The leads on the limbs: upper limbs (arms) and lower limbs (legs) refer to the heart in a vertical plane.

The ECG is printed on tracing paper. So the heart rate can be calculated from the big squares. This is achieved by counting the number of big squares between 2 R waves. Each big square is commonly 5 mm wide, representing 0.2 seconds. The number of squares is then divided by 300.

Figure 16. The positions of the leads on the upper and lower body to measure the heart activity.

What is heart disease?

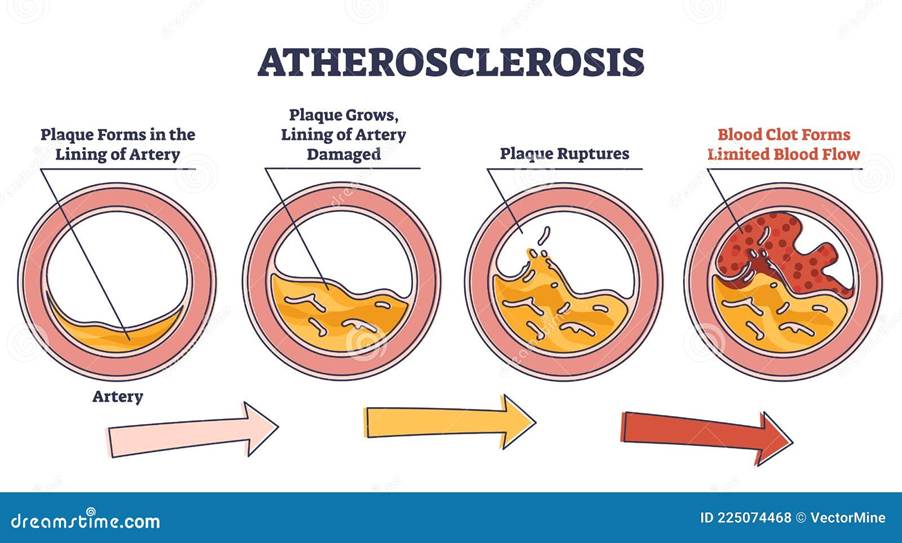

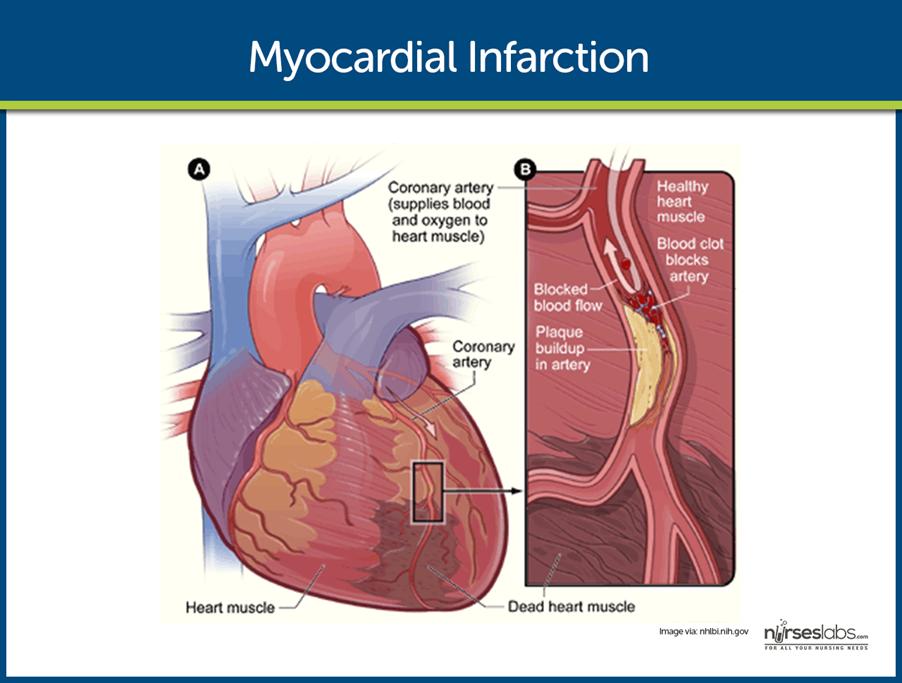

Cardiovascular disease is defined as a disease of the heart and can be subdivided into coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke. CHD is defined as the damage, weakening, or restriction of the heart’s blood supply. If the coronary arteries are damaged, it is referred to as coronary artery disease (CAD) (Aberystwyth University, n.d). CAD is mainly caused by atherosclerosis, the formation of fatty plaques deposited on the endothelial lining of the blood vessels. Please see Figure 17. They can become calcified, causing inflammation and blood clots (thrombosis), which narrows the artery. This increases blood pressure and the oxygen demand as the heart muscle works hard. If there is a complete blockage of the arteries, a heart attack occurs (myocardial infarction). Please see Figure 18.

Figure 17: Key steps involved in atherosclerosis

Figure 18: Myocardial Infarction

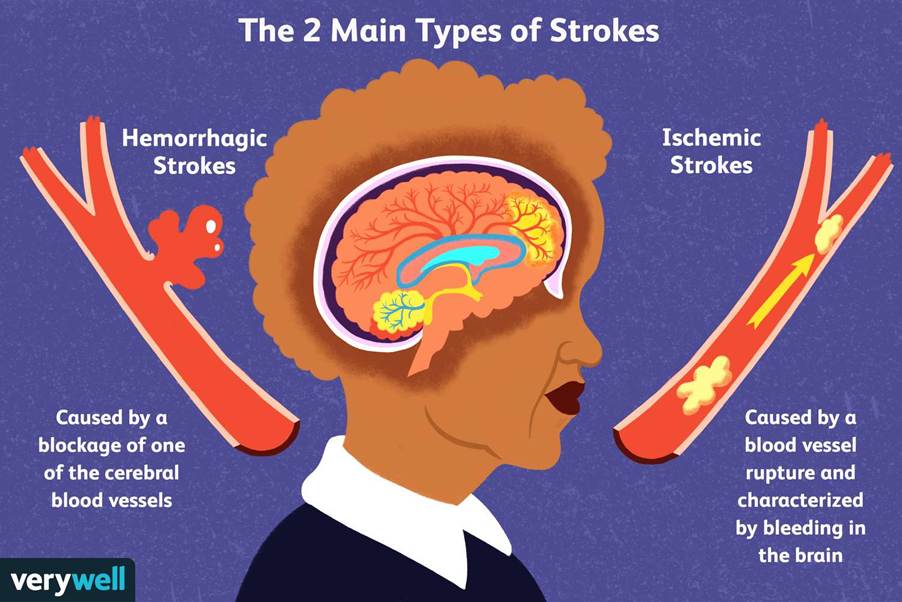

Stroke, otherwise known as apoplexy, is a sudden attack or weakness of one side of the body caused by a disruption to the blood flow in the brain. Ischaemic stroke occurs when the blood flow is prevented by blood clots (thrombosis) or by a detached clot from the heart or large blood vessel in the neck, like the carotid artery. Please see Figure 19. Haemorrhagic stroke is the rupture of the artery wall. Low blood pressure for a long period of time can cause brain damage.

A cardiac arrest is when the pumping action of the heart stops (asystole). There is normal electrical activity but no mechanical activity. There may be prolonged activity, or rapid, ineffective electrical and mechanical activity such as ventricular fibrillation. A heart murmur may occur if a leaky valve causes blood to flow wrongly. If the heart murmur is severe, it can cause major issues.

Figure 19: Types of stroke.

What’s the difference between a heart attack and a cardiac arrest?

Risk Factors And Causes Of Heart Disease

There are many risk factors of heart disease, and they are summarised in Table 1. Overweight, poor diet, and exercise increase the risk of blood glucose and blood pressure, causing Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (World Health Organisation, 2024; British Heart Foundation, 2024; Akhabue et al., 2014).

The leading metabolic risk factor for 25% of NCD cases globally is high blood pressure, followed by elevated blood glucose levels, and then overweight (World Health Organisation, 2024). The leading environmental risk factor is indoor and outdoor air pollution, which accounts for 6.7 million deaths, where 5.6 million are attributed to NCDs like stroke, ischaemic heart disease, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Stress can increase the risk of heart failure. When under stress, the heart has to beat faster. If this situation continues, then the heart is put under a great deal of stress, and this can lead to the heart stopping due to fatigue.

Table 1: A summary of risk factors for heart diseases.

| Lifestyle factors | Health Conditions/metabolic risk factors | Environmental risk factors |

| High calorie diet (fat and sugar) Poor exercise Smoking (first and second hand) Too much alcohol Older age Assigned sex at birth Family history | Excess weight Overweight Obesity Diabetes Type 2 Diabetes mellitus High Blood pressure (hypertension) > 140/90 mmHg High cholesterol (hypercholesteroleaemia) | Air pollution Occupation Radiation |

Lack of exercise also increases the risk of heart disease. The heart muscle needs to be exercised like any other muscle. Physical inactivity can cause the heart to not cope when it needs to beat quickly, for example, when running for a bus. Smoking increases the risk of heart disease because chemicals in cigarettes may make it more likely for the blood to clot, even when still inside the body. This can cause blockages and lead to heart failure.

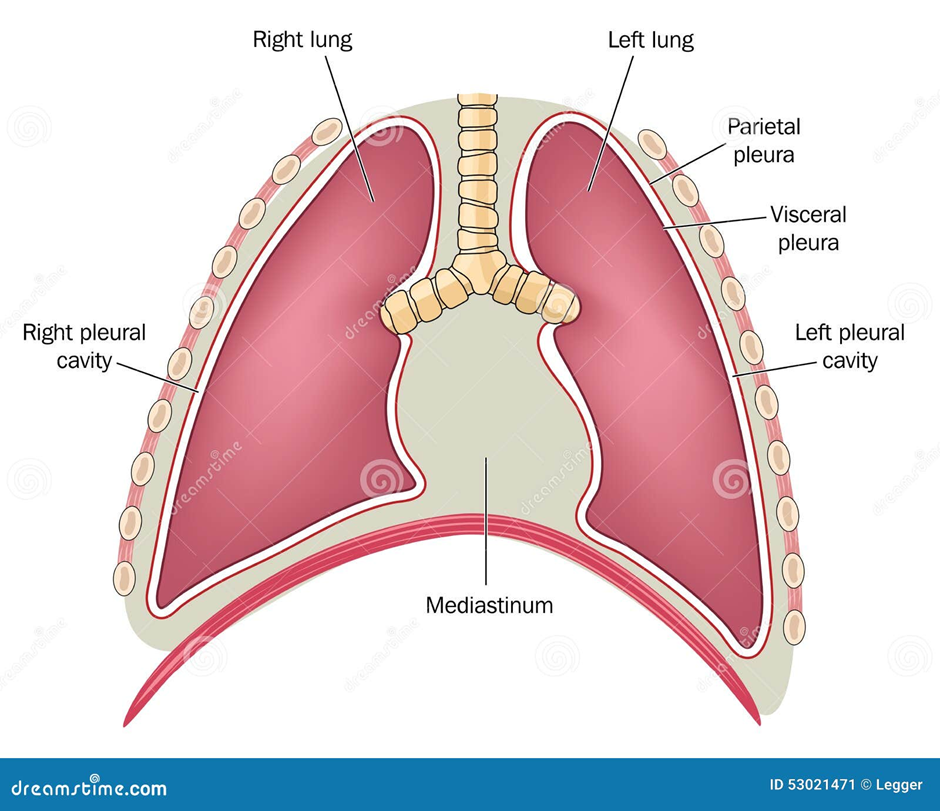

Having relatives with a current or previous history of heart disease increases the likelihood of getting heart disease. Moreover, multiple small population cohort studies linked previous radiation to the chest, especially the left chest area or the mediastinum, to the risk of developing heart disease and limiting the structural and functional effects of the heart post-radiation therapy (Akhabue et al. 2014). Please see Figure 20.

Figure 20: The mediastinum in the chest.

Several emerging risk factors of heart disease: coronary artery calcium score, lipoprotein Lp (a), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), C-reactive protein, carotid intima-media thickness, and homocysteine (Akhabue et al. 2014). Lp (a) is a low-density lipoprotein-like particle that has a large glycoprotein called apolipoprotein (a) linked to apolipoprotein B-100. A glycoprotein is a carbohydrate (sugar) attached to a protein. Apolipoprotein B-100 is the main lipoprotein found in low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Lipoprotein is a lipid/fat attached to a protein. A good example is cholesterol, and different forms of lipoprotein can lead to various clinical outcomes.

To find out more what food contains high levels of saturated fat and cholesterol, please visit British Heart Foundation:

LDL increases the presence of plaques, as presented in Figure 21. The plaque is composed of macrophages, LDLs, and impartial lipids/fats, with subsequent calcification and ulceration occurring around the outer part of mature plaques. This increases oxidative stress, stimulates inflammatory signaling, and breaks down the vasoprotective nitric oxide (NO) within the vascular endothelium (Judkins et al., 2010). Reactive oxygen metabolites are measured during early-staged atherosclerosis to detect oxidative stress.

Lipoprotein Lp (a)

Arnold et al. (2025) discovered that for patients with a low risk of CHD, the rise in levels of Lp (a) is a risk factor for adverse outcomes and can be modifiable. Lp (a) levels are low in regions in Europe, South-East Asia, and East Asia. Intermediate concentrations of Lp (a) in South Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East (Nordestgaard and Langsted, 2024). Elevated levels were found in people from Africa, where more than 90% is associated with genes and 17% occur in women after menopause (Nordestgaard and Langsted, 2024). This essentially represents the importance of measuring Lp (a), and there are no currently approved drugs to lower the concentration. Clinical trials revealed a minimum of five drugs that can lower the concentration of Lp (a) by 65-68%. Three are at endpoint trials (Nordestgaard and Langsted, 2024).

Finneran et al. (2021) revealed 86.8% of participants (298,461 of 343,728) had high levels of Lp (a) but no previous family history in first degree. 153228 patients had a follow-up time of less than 9 years (<9 years). This indicates that the risk of CAD can be refined for a broader aspect of primary prevention without having a family history of heart disease.

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2)

The inflammatory enzyme, Lp-PLA2, is otherwise known as platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. It is commonly expressed by inflammatory cells in the fatty plaques (atheroma) and found in conditions like acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina). These are disorders that encompass ischaemia with no myocardial damage, partial thickness non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and a full thickness ST elevation MI (STEMI) (Akhabue et al., 2014; Innes, 2009).

The Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration (2010) revealed that Lp-PLA2 activity was found in 57,931 subjects from 18 studies and Lp-PLA2 mass in 58,224 subjects from 21 studies. The activity of Lp-PLA2 was more strongly linked with lipid markers than mass. Perhaps, this may explain the difference in measurement with precision and distribution and lipoprotein classes (Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration, 2010).

Furthermore, several genetic indicators, like loss-of-function mutation of the Pla2g7 gene found in East Asia, can abolish Lp-PLA2. However, this has not been linked to vascular risk. The genotypes found in Europe had a weaker effect on Lp-PLA2. Randomised trials of Lp-PLA2 inhibitors can solidify whether Lp-PLA2 modulates and reverses vascular risk (The Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration, 2010).

Lp-PLA2 is bound to LDL to increase inflammation. Inflammation is produced by increasing arachidonic acid (AA) from the plasma membrane glycerophospholipids. AA is an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) that interacts with cytochrome P450 enzymes to undergo monooxygenation or epoxidation and produce hormone-like molecules, functioning as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (Younes, LeBlanc, Hiram, 2022).

Lp-PLA2 hydrolyses or breaks down oxidized phospholipids to damage the endothelial lining and promote the formation of plaque inflammation and arterial intima. It also increases vasoconstriction and proinflammatory signalling, via chemokines, interleukins, tumour necrosis factor alpha, macrophages, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Examples of chemokines are complement C3B, C5A, Chemokine C-X-C Motif ligand 1 (CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL8). Examples of interleukins are IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18. Collectively, these proinflammatory molecules increase expression of Intracellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1), Vascular Adhesion Molecule 1 (VAM-1), and E-selectin to act on endothelium and promote neutrophils to blood vessels. This speeds up the heart rhythm (cardiac arrhythmia) and atrial fibrillation (Younes, LeBlanc, and Hiram, 2022). Paradoxically, Lp-PLA2 hydrolyses platelet-activating factor (PAF) linked with anti-inflammation (Younes, LeBlanc, and Hiram, 2022).

Moreover, AA can interact with cyclooxygenase (COX1) and (COX2) to produce prostaglandin H2. This converts to proinflammatory lipids and mediates metabolites, for instance, thromboxane A2, prostaglandin A2 (PGA2), PGB2, PGE2, and PGI2. This increases atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and hypertension (Younes, LeBlanc, and Hiram, 2022).

Furthermore, adipocytokines, consisting of leptin, are produced in adipose/fat tissue. This implies that the endocrine function of adipose tissue can propagate vascular impairment, prothrombotic tendency, and occasional-grade continual inflammation (Anfossi et al. 2010).

Homocysteine

Similarly, high levels of the amino acid, plasma homocysteine, are associated with CAD. It can elevate stress that damages the endothelial lining, increase the recruitment of immune cells to induce attack, and promote the proliferation of smooth muscles and the coagulation cascade (Akhabue et al., 2014).

The normal concentration of homocysteine is between 5 and 15 µmol/L. High levels of homocysteine are related to sociodemographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and nutritional status of folate, vitamin B12, and renal and liver inflammation (Unadkat et al., 2024). Simultaneous to previous studies, Asians and Africans are at a higher risk of homocysteine than Europeans over the years.

The level of homocysteine is regulated by the enzyme methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). The MTHFR gene encodes the MTHFR enzyme and is involved in the metabolism and removal of homocysteine using folate. If a mutation or polymorphism of the gene occurs, MTHFR C677T lowers the effect of MTHFR and increases levels of homocysteine (Unadkat et al., 2024).

Energy drinks

Another risk factor of CAD is the consumption of energy drinks. Energy drinks may boost energy but can also increase blood pressure, as discovered by Dr Anna Svatikova and her team (Wanjek, 2015). It commonly affects even those who do not consume caffeine. Dr Svatikova gave 25 healthy volunteers aged between 19 and 40 an energy drink. On another day, the same participants drank a placebo drink as a test. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured before and after the drinks. The researchers revealed an increase in systolic pressure of 3 percent after drinking an energy drink. It is unknown whether the cause is caffeine, taurine, or other ingredients.

Caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist and stimulator of the central nervous system (Seifer et al., 2011). On a positive note, caffeine can treat temporary cessation of sleep and conditions like bronchopulmonary dysplasia. It also holds psychological effects such as improving cognition, mood, and sleep. According to Mayo Clinic, consuming 400 milligrams of caffeine daily is safe, which is like four brewed coffees, ten cans, and two energy shot drinks.

On a negative light, it can cause irritability, nervousness, anxiety, poor memory, substance abuse, hallucinations, palpitations, risk-taking behaviours, amongst other symptoms. It can also cause the coronary and cerebral arteries to undergo vasoconstriction. The smooth muscle is relaxed whilst there is stimulation of the skeletal muscle. There is low insulin sensitivity, and it can modulate gene expression in neonates. High levels increase the flow of urine and sweat. It is a mild diuretic < 500 mg /day but does not cause dehydration (Seifert et al., 2011).

It may be associated with body size, as a study discovered children at risk of cardiac abnormalities (Seifert et al., 2011).

Elevated expression of the amino acid taurine is present in the central nervous system. Taurine aids in growth, protection, metabolism, and homeostasis. Homeostasis is the maintenance of the internal environment. It can also treat congestive heart failure, dysarrhythmia, and palpitations.

Other ingredients found in energy drinks are Guarana, L-Cartinine, Yohimbine, and Ginseng. Guarana is a South American plant that contains high caffeine content. L-Carnitine is an amino acid involved in β-oxidation of fatty acids. Yohimbine is an alkaloid found in the plants (Seifert et al. 2011). Reports revealed that Yomhibine should not be taken with antipsychotics, stimulants, or medications that lower blood pressure. The East Asian herb, Ginseng, lengthens the time for bleeding and should not be combined with warfarin. It may also affect oestrogen and corticosteroid, and can lower blood glucose levels and digoxin metabolism (Sieitfet et al. 2011). Digoxin can be administered orally or via injection and is used to treat heart failure and atrial fibrillation; irregular heart beat and activity of the atria.

Figure 21: The difference between high and low density lipoprotein.

Signs And Symptoms Of Heart Disease

Amongst the common symptoms of heart disease are acute chest pain and discomfort. There are cardiac and non-cardiac causes of chest pain, and they can be differentiated based on site, other symptoms experienced, and characteristics (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

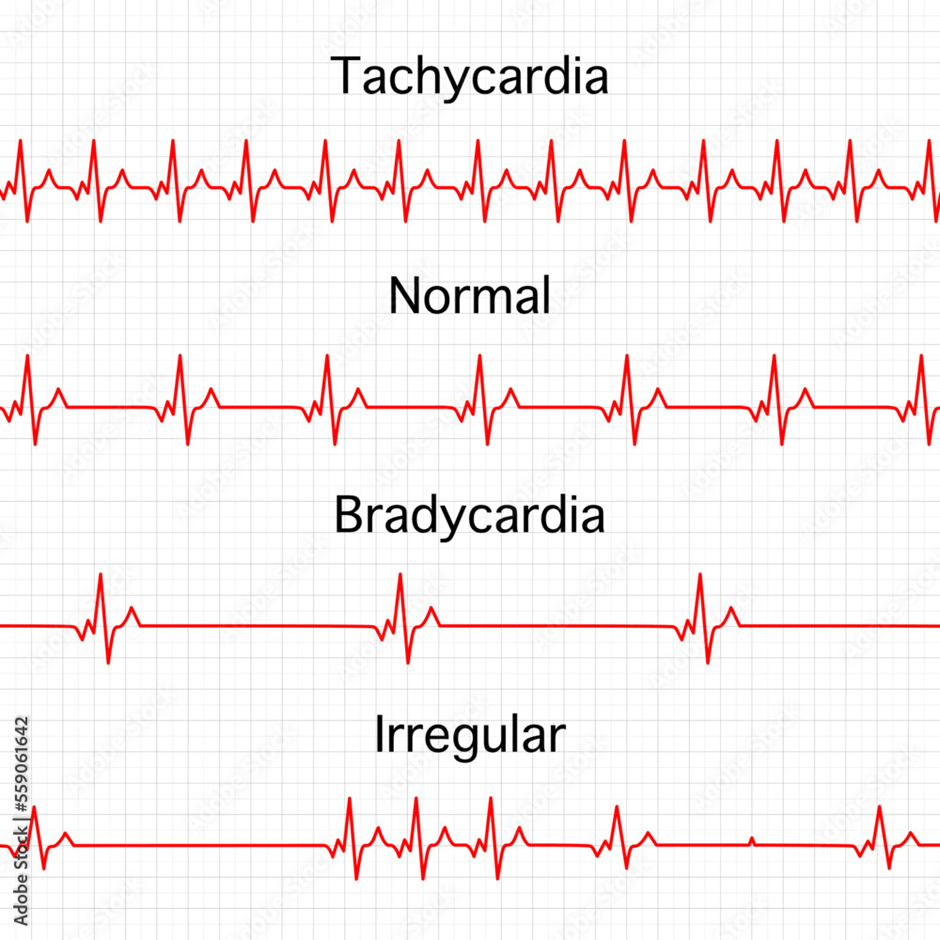

Dyspnoea is the shortness of breath. Orthopnoea is the lack of breathing or breathlessness. There is a redistribution of blood to increase the volume of pulmonary blood. Palpitations commonly appear when there is anxiety. Dizziness and lack of consciousness (syncope) may arise and are associated with the presence of fat or slow heart rates (bradycardia) (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Tiredness, lethargy, and exertional fatigue may also be experienced by some patients. Oedema, a build-up of fluid, may occur as a result of heart failure (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Changes in the ECG patterns

Sinus conditions are common variations that appear in the heart rhythm when breathing in healthy patients. Pathological conditions are disease states.

A high ST segment that is more than 1mm ( > 1mm) represents the early stages of myocardial infarction (MI)

A depression of the ST segment > 0.5 mm below the isoelectric line represents myocardial ischaemia.

A 24-hour monitoring and recording of ECG when symptoms occur to detect abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia).

Sinus arrhythmia: This is common due to fluctuations or changes in the autonomic tone when breathing in (inspiration) during the rest and digest state (parasympathetic tone). The heart rate rapidly increases and then decreases upon breathing out (expiration).

(Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003)

Bradycardia

It is a slow heart rate, less than 60 bpm (<60 bpm). Please see Figure 22 for an example of ECG pattern.

Causes Of Sinus bradycardia:

This occurs during sleep or in well-trained athletes

Causes Of Pathological bradycardia:

Hypothermia (low temperature)

Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland)

Jaundice (abnormal production of the protein bilirubin, which causes yellowing of the skin and eyes)

High intracranial pressure (high pressure in the brain

Drugs (Beta blockers, digitalis, and other drugs used in treatment for arrhythmia).

Intermittent failure of the SA node, which explains why the P wave has a long pause that lasts more than 2 seconds ( > 2s).

Atrioventricular block:

There are three main types:

First-degree atrioventricular block: The conductivity of the AV node is delayed, which causes a prolonged PR interval that lasts more than > 0.2 seconds. It rarely causes symptoms.

Second degree or partial atrioventricular block: This presents some signals arising from the atria that fail to conduct to the ventricles, which decreases the heart beat. There are two types of second-degree blocks:

Mobitz Type 1 block: Wenckebach’s phenomenon, where there are repeated cycles of progressive lengthening of the PR intervals in a dropped beat. It is common at the resting state or during sleep.

Mobitz Type 2 block: The PR interval of conducted impulses remains constant, whereas some P waves are not conducted. It is caused by a disease of the His Bundle and Purkinje fibre system. There is a risk of asystole (the heart stops working). In 2:1, the AV block alternates, so the P waves are conducted, so we cannot tell the difference between Mobitz type 1 and type 2.

Third-degree or complete atrioventricular block: This may arise when there is no link between the atria and ventricular activity. They function independently. The activity of the ventricles is maintained by an escape rhythm.

An escape rhythm that arises in the AV node or Bundle of His is the narrow QRS complex.

An escape rhythm that arises in the distal Purkinje fibers has a broad QRS complex.

(Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003)

Tachycardia

They have a heart rate of more than 100 bpm (> 100 bpm). Please see Figure 22 for an example of ECG pattern.

Causes Of Sinus Tachycardia:

This may occur during excitement and exercise.

Causes Of Pathological tachycardia:

Fever, anaemia, cardiac failure, and drugs (atropine and catecholamines).

Arrhythmia, or premature discharge of an ectopic focus in the atria: It is the discharge before the next sinus impulse. There is an early and abnormal P wave followed by a normal QRS complex.

Atrial flutter: This is linked with organic disease of the heart. The heart rate is about 300 beats per minute, where the AV node conducts a second flutter beat, giving a ventricular rate of 150 beats per minute. The ECG has flutter F waves that appear like a ‘saw tooth’ on the ECG trace.

Supraventricular tachycardia arises from the atrium or atrioventricular junction.

Ventricular tachycardia: They arises from the ventricles. There are three or more consecutive ventricular beats that occur at a rate of 120 per minute or more. There is a broad abnormal QRS complex.

(Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003)

Figure 22: Pathological ECG patterns

For further tests and diagnosis besides ECG, please visit NHS

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronary-heart-disease/diagnosis/

Treatment Of Heart Disease

According to the British Heart Foundation, CVD accounts for ca. one in four deaths in the UK. The main focus for treatment is to manage lifestyle factors such as regular exercise and decrease cholesterol to < 5 mmol/l. To lower high blood pressure, a modified weight loss plan that may include low alcohol intake, restricted salt, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, especially in patients with cholesterol levels greater than 4.8 mmol/L, and other lifestyle modifications is currently believed to surpass the potential effects of pharmacological treatment. Treatment is dependent on age, condition, weight, height and clinical history and medications taken by the patient.

Pharmacological treatment of heart disease

On the contrary, there are many beneficial effects of taking medications to treat heart disease. Statin helps to lower serum cholesterol concentration. This prevents 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase, a rate-limiting enzyme essential in the production of cholesterol in the liver.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are prescribed to lower blood pressure to a target of < 130/80 mmHg. ACE prevents the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II and also inhibits the breakdown of the vasodilating hormone bradykinin. Angiotensin is an oligopeptide that stimulates the release of the aldosterone hormone from the adrenal cortex in the adrenal gland. This produces oxidative strain and damage to the endothelial lining of the blood vessels. Further constriction of the blood vessels may occur as a result of these dysfunctional changes (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Aspirin

A healthcare professional may prescribe 75 mg of Aspirin daily. This lowers the risk of heart attack by irreversibly inactivating the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) in platelets. Platelets are small fragments that help clot the blood. Inactivation of COX can halt the production of thromboxane A2 that mediates platelet aggregation. It also prevents the synthesis of proinflammatory prostaglandins (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers are useful for angina (chest pain) but should be avoided in patients with asthma. A healthcare professional commonly prescribes Atenolol (50-100 mg) and metoprolol (25- 50 mg) to be taken twice daily. This lowers the heart rate and increases ventricular contraction, thereby reducing the oxygen demand in the cardiac muscle (myocardium) (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Calcium antagonists

Calcium antagonists like amlodipine block calcium influx into cells. This helps the coronary arteries to relax, decreases left ventricular contractility, and lowers oxygen demand and chest pain (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Nitrates and GTN spray

Nitrates lower venous and intracardiac diastolic pressure. This helps to dilate the coronary arteries (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate GTN as a spray or tablet relieves pain in the chest (angina) (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Surgery

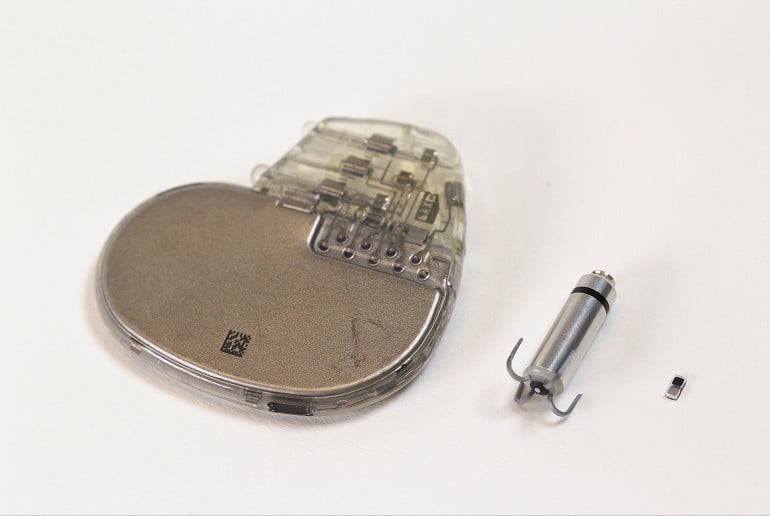

Artificial Pacemaker

If lifestyle factor changes do not help, nor medications, then surgery is applicable. An artificial pacemaker can be fitted to help correct issues in the heart’s conduction system. An electrode is fitted to the atrium and another to the base of the ventricles. The artificial pacemaker sends out regular pulses of electricity down these electrodes to stimulate the heart to beat regularly.

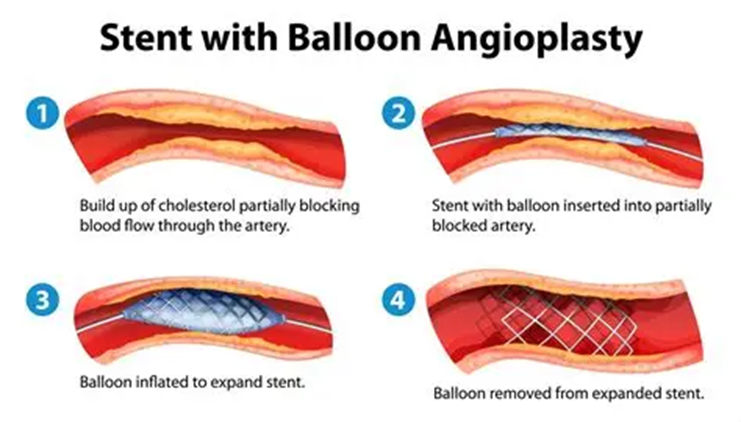

Percutaneous coronary intervention

A fine guided wire is used to position a small inflatable balloon in a blocked or near blockage vessel coronary arterial stenosis. Arterial stenosis is the expansion of the vessel, and this may cause insufficient blood supply to organs and may result in the rupture of the blood vessel. A stent coated with metal scaffolding is added to a balloon to maximise dilation. Please see Figure 23. This is commonly used in two-vessel disease. Aspirin and antiplatelet drugs like clopidogrel are routinely given.

Figure 23: Stent with balloon angioplasty

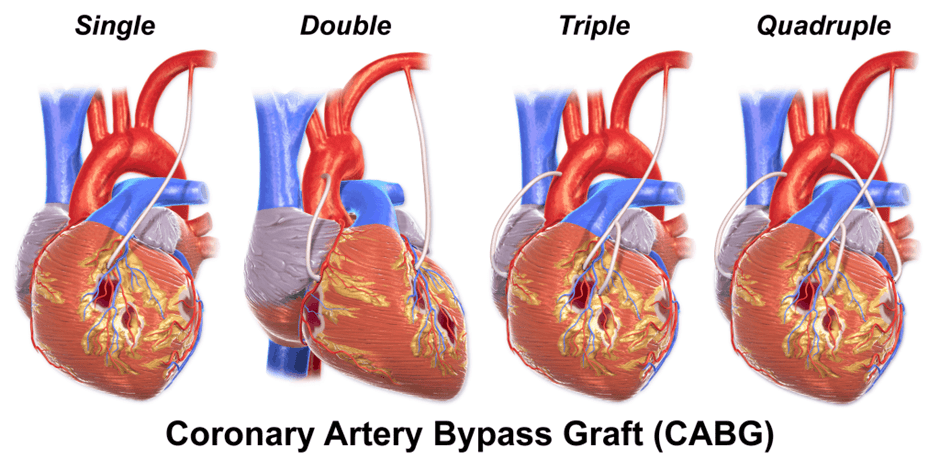

Coronary artery bypass grafting CABG

This is an operation that aims to divert the blood flow from a damaged or blocked blood vessel. Arteries in the radius from the arms, left or right internal mammary, or saphenous from the leg can be used to bypass the coronary artery in the left anterior or right coronary artery, respectively. Saphenous blood vessels are less commonly used to join with the proximal aorta. This helps to relieve angina in 90% of cases and improve lifestyle. This operation is frequently used in the elderly to help improve survival rates, especially with rising issues in left ventricular function. Aspirin helps to improve graft patency, and lowering lipid levels can slow the progression of disease in coronary arteries and grafts (Innes 2009; Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Figure 24: Different types of CABG

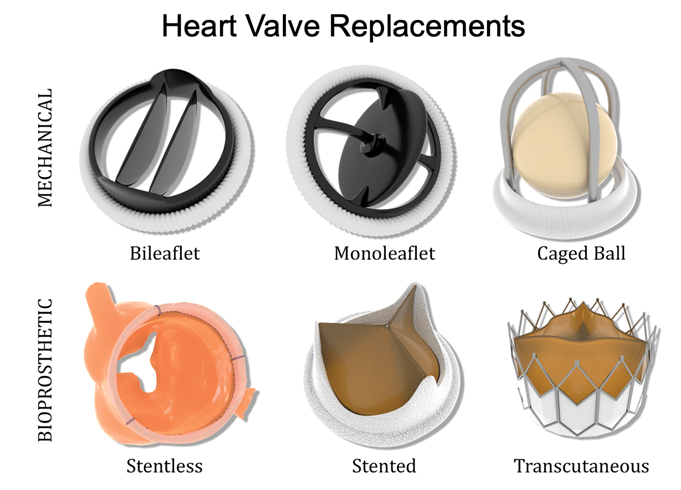

Prosthetic valves

When there are leaky valves, murmur sounds are formed that reflect circulatory abnormalities. Abnormal valves produce turbulent flow to reflect how cardiac valves can be regurgitant. This is diagnosed by a procedure called echocardiography and measured by Doppler echocardiography to monitor the direction and speed of the blood flow. It can be treated medically or via surgery, where the removal of the valve (valvotomy), repair, or replacement of the damaged valve takes place. Time is a critical factor, and the sooner the operation, the better the subsequent clinical outcomes and recovery time.

There are two types of prosthetic heart valves: tissue or mechanical – please see Figure 25. Biological tissue valves are from pig aortic valves, porcine xenografts, but sometimes a human aortic valve homograft is used. Sometimes, bovine cow pericardium can make tissue valves. They tend to degenerate after 10 years, but patients do not need long-term anticoagulants. On the other hand, mechanical valves last a minimum of 20 years, and there is a dire need for lifelong anticoagulants.

There are different designs of mechanical valves: ball and age designs, otherwise known as the Starr-Edwards valve, developed in the late 1950s. The Tilting disc, otherwise referred to as the Björk-Shiley valve, was developed in the 1970s. The third design is St. Jude’s valve, or Bileaflet, formed in 1978. They vary in the orientation and blood flow pattern (Laas et al., 1999). Valves susceptible to infection and thrombosis, which can cause haemolysis and systemic emboli. Damage to prosthetic valves, like any operation, is at risk of infection (Ballinger and Patchett, 2003).

Figure 25: Types Of Valves

New Non-Surgical Cardiac Discovery!

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) is a lifesaving procedure conducted in cases of cardiac arrest where the heart or breathing has stopped. Please see Figure 26. The method varies with age. Below are different formats to understand what the technique involves:

Figure 26: Visual presentation of CPR.

NHS Step By Step written process for adults, children and under one years of age:

https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/first-aid/cpr/

NHS Wales: CPR training video format

Natural Remedies

Honey

The earliest records of beekeeping were in Cairo in 2400 BC. The Ancient Egyptians used honey as a sweetener and embalming fluid, whereas the Ancient Greeks observed honey as a healing medicine. It was considered an important food in many countries in Europe and worldwide. However, when sugar arrived, the usage of honey as a sweetener was reduced; instead, it was employed as a complementary treatment for wounds, gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular-related, and liver-related issues.

To maximise honey production, honeybees fan the honeycomb via their wings to evaporate water from nectar. Honeybees collate nectar and sap from the timber and blend them with enzymatic secretions in their glands, transglucosylase, and glucose oxidase. Transglucosylase hydrolyzes sucrose to help break it down into glucose and fructose. On the other hand, glucose oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of glucose to form gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Honey primarily consists of two simple sugars (monosaccharides): fructose and glucose. Other constituents include oligosaccharides (short sugars), minerals, amino acids, vitamins, and enzymes. Honey contains chemicals that work effectively as a synergistic antioxidant, for instance, flavonoids, catalase, and ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Flavonoids lower the chance of heart disease by preventing low-density lipoproteins (LDL) from oxidation. It also decreases the ability of platelets to clot the blood and improve coronary vasodilation. There are various subgroups of flavonoids in honey that have shown cardioprotective effects: flavanone, flavone, and flavonol. For example, Naringenin is a type of flavanone and has antiatherogenic properties; it prevents the formation of atheroma/atherosclerotic plaques. Pinocembrin and Hesperetin are other examples of flavanones, and they relax the blood vessels (vasorelaxation).

Similarly, acacetin, apigenin, chrysin, and luteolin have a vasorelaxing effect, but they belong to a group called flavones. These flavones also have other functions. Apigenin protects cardiac muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) and chelates iron present inside cells, and suppresses hydroxyl radical production. Luteolin and chrysin prevent atrial fibrillation (abnormal contraction of the atria), and acacetin prevents arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm).

Another group of flavonoids is flavonols. Quercetin and Kaempferol lower blood pressure, are antiplatelet, and promote endothelial relaxation of coronary arteries. Apigenin and Luteolin significantly inhibit NF-KB transcriptional activation that was induced by tumour necrosis factor alpha (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Polyphenols are found in honey. They stimulate the proliferation of B and T cells, where they recognise, destroy pathogens, and produce antibodies. They can stimulate monocytes to release inflammatory cytokines.

Phenolic compounds in honey are effective against coronary heart disease as they hold anti-oxidant, anti-ischaemic, vasorelaxant, and anti-thrombotic properties. This decreases oxidative stress, lowers lipid peroxidation, decreases blood pressure, and increases the function of the endothelial cells (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Nitric oxide (NO) levels in honey have a protective effect against cardiovascular diseases (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Propolis is a herbal resinous substance found in honey. Please see Figure 27. They hold antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, vasoprotective, and antiprotective mechanisms. It has high flavonoid and polyphenol content. This lowers the risk of heart disease in patients with metabolic risk factors such as hypercholesterolemia, overweight, poor exercise, and hyperglycaemia (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Surprisingly, researchers have revealed that wild honey from the nectar of a few species of rhododendron is considered toxic and poisonous. The naturally occurring sodium channel toxin, grayanotoxin, causes life-threatening bradycardia, hypotension, and altered mental status (Dubey et al. 2009). Some honey from the Northern parts of Turkey can be poisonous because of grayanotoxins and romedotoxins present in the product. This is overcome by plants from the Ericaceae family (Akinci et al. 2008; Okuyan et al. 2010). Researchers have advised reviewing patients with clinical presentation of bradycardia and hypotension in emergency departments. Perhaps, it may be a case of intoxication by eating leaves from the Rhododendron or Ericaceae species (Haider and Kumari, 2024).

Figure 27: Bee Propolis of honey

Avocado

Avocado is a green, rich, creamy fruit that has been native to Central and South America for centuries. One of the most popular species is the Hass avocado. The medium-sized fruit has a dark green or black skin. It is estimated that 136 g of avocado fruit contains ca. 13 g of oleic acid. Half of an avocado has the following, which helps improve heart health (Corliss, 2022; Pacheco et al., 2022):

- Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid. Half an avocado has 6.5 g of oleic acid. This equals the same as a tablespoon of olive oil. Oleic acid helps overcome endothelial dysfunction, lower blood pressure, and inflammation. Oleic acid sensitizes insulin, lowering insulin resistance and regulating blood glucose levels. It also increases the presence of high-density lipoproteins. Avocado is a good example of unsaturated fats, besides nuts and seeds, that lower LDL.

- 20% daily recommended fibre. It helps break down food and decreases the risk of heart disease by 30%. Fibre lowers cholesterol, blood pressure, and body weight. However, it requires balance; too much avocado can lead to being overweight despite being a monounsaturated fat.

- Omega-3 fatty acids lower cholesterol.

- Protein strengthens bones and is essential for growth and repair.

- Carbohydrates: energy

- 10% potassium regulates sodium chloride, and high levels of sodium chloride increase blood pressure.

- 5% magnesium

- 15% folate (folic acid) B9 regulates the amino acid homocysteine, which helps prevent CVD risk. It also helps with blood cell growth and development.

- Other vitamins, B12, B4, B5, E, and K, maintain the regulation of the body.

- 7.5 g monounsaturated fatty acid

- 1.5 g of polyunsaturated fatty acid

- High beta-sitosterol compounds: 136 g of fruit without skin and seed contains 104 mg of beta‐sitosterol.

- Lycopene and beta carotene are antioxidants, and high concentrations reside in the dark green area of skin, which helps lower cell damage. (Corliss, 2022; Pacheco et al., 2022).

- Glutathione strengthens the immune system (Corliss, 2022; Pacheco et al., 2022).

A long-term study interviewed 110,000 people from the Nurses’ Health Study (68786) and Health Professionals Follow-up study (41791 men, 1986-2016). Participants ranged from 30 to 75 years and were not diagnosed with either heart disease or cancer when the study was initiated. This is referred to as the baseline. Most subjects were Caucasian. Diet was assessed by questionnaire and then every 4 years, which included whether they consume avocado and the quantity. During the 30-year follow-up, there were 14274 cases of CVD, 9185 cases of heart attacks, and 5290 strokes. Participants who ate two servings of avocado per week had a 16% lower risk of CVD and 21% risk of heart attack and CAD. (Corliss, 2022; Pacheco et al., 2022).

Risk tools

Identification of future risks of cardiovascular disease is an integral part of the routine NHS Health Check. Currently, QRISK is applied to over 5 million patients annually. It forms part of the UK Government’s 10-year plan as a preventative measure to maintain an efficient patient care system. The annual healthcare costs leaped to an astonishing 10 billion pounds a year (NIHR Evidence, 2025).

The QRISK 4 tool

The National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHCR) reported in July 2025 several new techniques used to identify patients at risk of heart disease and stroke (NIHR Evidence, 2025). A new cardiovascular risk calculator, QRISK4 (QR4), can estimate patients at risk of CVD within a decade. Researchers at the University of Oxford determined this after collecting information on age, sex, blood pressure, and medical history for early intervention with inclusivity and diversity.

This new initiative replaced the QRISK3 (QR3) tool recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for patients aged 25 to 84 years. QRISK3 was developed based on a diverse population of 7.9 million people. It lowered the risk of missed results or false positive/negative results (King’s College London, 2024; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2024). The overall CVD rate per 1000 person-year was 4.03 during the COVID-19 pandemic, but rose to pre-pandemic levels of 4.31 in 2021. These rates are much lower than the mortality rates of non-CVD. There is an increasing trend for NON-CVD deaths from 3.45 in 2019 to 3.84 in 2020 and remained high in 2021 (King’s College London, 2024; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2024).

In Europe, guidelines recommend the SCORE2 programme, which originated from patient data (677684 cases). The SCORE-OP programme has 28503 cases residing in Norway. The United States of America (USA) recommended the ASCVD score based on Pooled Cohort Equations, and participants from non-Hispanic/Latino (20338 cases) and African American (1647 cases) (King’s College London, 2024; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2024).

The risk factors explored by QR4 were differentiated into all adults and those specific to female patients. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Down Syndrome, Learning disability, and cancer (blood, lung, brain, and oral) were for all adults as they affect cardiovascular health. Risk factors for women are pregnancy complications like pre-eclampsia and postnatal depression that are predictive of future CVD risk. Pre-eclampsia is characterised by high blood pressure and protein in the urine (proteinuria) that commonly occurs in pregnant women aged 20 weeks and above or after labour (baby delivery). The cause is unknown and is associated with placental dysfunction (National Health Service, 2021). Women with COPD are at higher risk of CVD (King’s College London, 2024; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2024).

The ECG-AI tool

Another discovery announced by the NIHCR was an ECG enabled by artificial intelligence (AI) to help improve diagnosis and detect patients at risk of mortality. The risk estimate platform of AI-ECG (AIRE) accurately predicted based on the C-statistic, otherwise known as concordance or C-index. The C-index measured the goodness of fit in a logistic regression model. It estimates the probability of randomly selecting a patient who experiences a disease with a more elevated risk score than a patient who has not experienced the event/disease. There are reference ranges that correlate with the strength of the modelling system. A value less than 0.5 indicates a poor model. Values above 0.7 but below 1 are a good model. A strong model has a value over 0.8. The 0.5 model is not better than predicting the outcome by random chance. A value of 1 suggests a model is perfect to determine whether members will experience a certain outcome and those who will not.

The data presented by Sau et al. (2024) suggests it was a good model. In descending order, the values for future heart failure (0.787), mortality for all causes (0.775), ventricular arrhythmia (0.760), and future atherosclerotic CVD (0.696). This suggests how accurate long-term or short-term estimates are from a single ECG-AI. However, this data requires clinical, biochemical, and imaging data to effectively become actionable as time-to-event predictions and specific predictions for disease and disease-modifying treatments are vital. The low-risk population has a high negative predictive value. Higher-risk populations help identify patients at risk of adverse events.

Moreover, the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk predictor (AIRE-ASCVD) in 2024 surpassed the SEER 2023 AI-ECG model. It took into consideration systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, hypertension, smoking history, diabetes, and ethnicities. Similar performances were found in all genders and most ethnicities (Sau et al., 2024).

In contrast, the risk factors for heart failure, Atherosclerotic Risk in Communities (ARIC), were body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, previous atherosclerosis, diabetes, smoking, previous MI, hypertension, and ethnicities (Sau et al., 2024). Predicting heart failure is essential as the number of hospital admissions is increasing. Early clinical assessment, echocardiography, and therapies of adverse events are paramount (Sau et al., 2024).

CT risk assessment tool

The third diagnostic technique announced by the NIHCR discovered that computed tomography (CT) can predict risk by using fat tissue. CT is a standard radiological technique for chest pain, where there is a clinical presentation of atherosclerotic plaques in the arterial wall. However, if narrowed arteries are present, management is unclear, and most patients are likely to be discharged and end up later being diagnosed with heart disease. This highlights that heart scans cannot detect inflammation of arteries in all cases. Ultrasound is a radiological technique that depends on sound waves to create an image. Calculating the thickness of the carotid intima-media (CIMT) is a potential marker for atherosclerosis and risk for CVD (Akhabue et al., 2014).

Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography (CCTA) can help guide revascularization in patients without obstructive CAD and unclear prognosis. This is achieved by measuring the perivascular fat attenuation index (FAI) score, and can monitor radiological changes in the perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT). Chan et al. (2024) discovered from their longitudinal cohort studies of 40091 patients in 8 UK hospitals. They had a follow-up of myocardial infarction, heart failure, or cardiac death (MACE) with a median of 2 to 7 years. This group of patients is referred to as Cohort A. There was 81.1% of patients had no obstructive CAD and accounted for 2857 of 4307 total mass and 1118 of 1754 cases of cardiac deaths in Cohort A.

Having high levels of FAI in all three coronary arteries increased cardiac mortality or Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). This was independent of cardiovascular risk factors and the presence of CAD. The AI-Risk classification was positively associated with cardiac mortality, where the p-value was 0.001 for very high-risk mortality compared to low or medium-risk mortality. There was also a significant difference between MACE, where the p-value was 0.001 for very high risk in comparison to low or medium risk. Conversely, patients with obstructive CAD had higher MACE and cardiac mortality, MI, heart failure, ischaemic stroke, and all-cause mortality, excluding congenital heart disease or heart transplant (Chan et al., 2024).

In Cohort B, 3393 patients had a longer follow-up of 7.7 years. The FAI score in patients with and without obstructive CAD was consistent in all three coronary arteries. There was residual inflammatory risk beyond clinic risk, which was captured by the FAI score after adjustments were made for risk factors and non-obstructive atheroma/atherosclerotic plaques. Examples of cardiovascular risk factors are smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis (coronary artery stenosis) (Chan et al. 2024).

In all three novel assessment procedures, the importance of Risk stratification tools in patients with and without obstructive CAD. Measuring coronary inflammation by the FAI score could be used to monitor CVD events and dose response for affected coronary arteries. It also allows optimising of lipid-lowering treatment, for instance, statins and anti-inflammatory therapies, and to reclassify patients by their health status, risk factors, and the signs and symptoms experienced.

Conclusion

Overall, coronary artery disease accounts for millions of deaths globally. A combination of lifestyle modifications and risk-stratification tools as part of screening can help increase survival rates and alleviate the global burden of CVD. The number of deaths related to heart disease increased from ca. 19 million in 2021 to 19.8 million in 2022 (World Health Organisation, 2024; 2025). About 80% of patient cases occurred in low and middle-income countries (World Health Organisation, 2025). To date, there are multiple causal factors and underlying determinants of CVD that drive social, economic, and cultural transformation. Raising awareness can help lead to successive outcomes in primary and secondary care interventions through hypertension programmes, evidence-based guidelines for CVD, acute coronary syndrome, and stroke. The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013-2020 brought a positive light with the aim of decreasing premature mortality rates by 25% in 2025. The aim is to focus on declining hypertensive events and to increase accessibility for eligible patients (a minimum of 50%) to drug therapy and counselling to prevent heart attacks and strokes (World Health Organisation, 2025). Our understanding of the physiological and pathological states of the cardiovascular system steadily increases over time due to advances in diagnosis, ongoing progress, and multiple available therapeutic modalities of cardiovascular health. It is essential to maintain a momentum of how many of the causal factors are preventable and to take heed.

References

Aberswyth University (n.d.) Cardiovascular System Available at: https://www.aber.ac.uk/en/media/pdfmedia/publications/The-Cardiovascular-System.pdf (Accessed: 27th June 2025)

Akhabue, E., Thiboutot, J., Cheng, J., Lerakis, S., Vittorio, T.J., Christodoulidis, G., Grady, K.M. and Kosmas, C.E. (2014). New and Emerging Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 347(2), pp.151–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/maj.0b013e31828aab45.

Alibhai A, Stanford K, Rutland S and Rutland CS (2020) Hearts, and the Heartless, in the Animal Kingdom. Frontiers For Young Minds. 8:540440. doi: 10.3389/frym.2020.540440

Ballinger, A. and Patchett, S. (2003) Saunder’s Pocket Essentials of Clinical Medicine. London: Elsevier.

British Heart Foundation (2024) How your heart works Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/how-a-healthy-heart-works (Accessed: 27th July 2025)

Chan, K., Wahome, E., Apostolos Tsiachristas, Antonopoulos, A.S., Patel, P., Lyasheva, M., Kingham, L., West, H., Oikonomou, E.K., Volpe, L., Mavrogiannis, M.C., Nicol, E., Mittal, T.K., Halborg, T., Kotronias, R.A., Adlam, D., Modi, B., Rodrigues, J., Screaton, N. and Kardos, A. (2024). Inflammatory risk and cardiovascular events in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: the ORFAN multicentre, longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet, 403(10444), pp.2606–2618. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00596-8.

Corliss, J. (2022) Enjoy avocados? Eating one a week may lower heart disease risk Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/enjoy-avocados-eating-one-a-week-may-lower-heart-disease-risk-202204112725 (Accessed: 27th July 2025)

Finneran, P., Pampana, A., Khetarpal, S.A., Trinder, M., Patel, A.P., Paruchuri, K., Aragam, K., Peloso, G.M. and Natarajan, P. (2021). Lipoprotein(a) and Coronary Artery Disease Risk Without a Family History of Heart Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.120.017470.

Haider, R., Das, G.K., Ahmed, Z. and Zameer, S. (2024), Honey for Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal Of Clinical Chemistry, 3(5). DOI:10.31579/2835-8090/011

Hippisley-Cox, J., Coupland, C.A.C., Bafadhel, M., Russell, R.E.K., Sheikh, A., Brindle, P. and Channon, K.M. (2024). Development and validation of a new algorithm for improved cardiovascular risk prediction. Nature Medicine, [online] 30(5), pp.1440–1447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02905-y.

Innes, A. (2009) Davidson’s Essentials of Medicine. London: Elsevier

King’s College London (2024) New heart disease calculator could save lives by identifying high-risk patients missed by current tools. Available at: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/new-heart-disease-calculator-could-save-lives-by-identifying-high-risk-patients-missed-by-current-tools (Accessed: 27th July 2025)

Laas, J., Kleine, P., Hasenkam, M.J. and Nygaard, H. (1999). Orientation of tilting disc and bileaflet aortic valve substitutes for optimal hemodynamics. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 68(3), pp.1096–1099. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00780-8.

National Health Service (2021) Overview -Pre-eclampsia. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pre-eclampsia/ (Accessed: 30th July 2025)

NIHR Evidence (2025) Cardiovascular disease: new ways to detect risk and improve outcomes. Available at: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/cardiovascular-disease-new-ways-to-detect-risk-and-improve-outcomes/ (Accessed: 28th July 2025)

Nordestgaard, B.G. and Langsted, A. (2024). Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. The Lancet, 404(10459). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)01308-4.

Pacheco, L.S., Li, Y., Rimm, E.B., Manson, J.E., Sun, Q., Rexrode, K., Hu, F.B. and Guasch‐Ferré, M. (2022). Avocado Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in US Adults. Journal of the American Heart Association, 11(7). doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.024014.

Romero, N. (2024) Do insects have hearts?. Available at: https://www.animalwised.com/do-insects-have-hearts-4809.html (Accessed: 29th July 2025)

Sau, A., Libor Pastika, Sieliwonczyk, E., Konstantinos Patlatzoglou, Ribeiro, A.H., McGurk, K.A., Boroumand Zeidaabadi, Zhang, H., Krzysztof Macierzanka, Mandic, D., Sabino, E., Giatti, L., Barreto, S.M., do, L., Ioanna Tzoulaki, O’Regan, D.P., Peters, N.S., Ware, J.S., Luiz, A. and Kramer, D.B. (2024). Artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram for mortality and cardiovascular risk estimation: a model development and validation study. The Lancet Digital Health, [online] 6(11), pp.e791–e802. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(24)00172-9.

Seifert, S.M., Schaechter, J.L., Hershorin, E.R. and Lipshultz, S.E. (2011). Health Effects of Energy Drinks on Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Pediatrics, 127(3), pp.511–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3592.

The Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration (2010) Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. The Lancet, 375(9725), pp.1536–1544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60319-4.

Unadkat, S.V., Padhi, B.K., Bhongir, A.V., Gandhi, A.P., Shamim, M.A., Dahiya, N., Satapathy, P., Rustagi, S., Khatib, M.N., Gaidhane, A., Zahiruddin, Q.S., Sah, R. and Abu Serhan, H. (2024). Association between homocysteine and coronary artery disease—trend over time and across the regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Egyptian Heart Journal, 76(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-024-00460-y.

Wanjek, C. (2015) Energy Drinks Raise Blood Pressure, Study Finds. Available at: https://www.livescience.com/50178-energy-drinks-blood-pressure.html (Accessed: 29th July 2025)

Widmaier, E., Raff, H., Strang, K. (2006) Van der’s Human Physiology New York: McGraw-Hill

World Health Organisation (2024) Noncommunicable diseases Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (Accessed: 27th July 2025)

World Health Organisation (2025) Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (Accessed: 2nd August 2025)

Younes, R., LeBlanc, C.-A. and Roddy Hiram (2022). Evidence of Failed Resolution Mechanisms in Arrhythmogenic Inflammation, Fibrosis and Right Heart Disease. Biomolecules, 12(5), pp.720–720. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12050720.

One response to “Non-Communicable Diseases: Chapter Series (Part One)”

-

[…] Coronary Heart Disease (PART 1) […]

LikeLike

Leave a comment