Part Two: Raising Awareness On The Importance of Blood Donation

Written by Kandeel Butt: 25th March 2015

Updated by Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas: August 2025

Review date by Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas: August 2027

Blood is a life-saving liquid organ composed of oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and antibodies that nourish our lives and protect our bodies from infection (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014). Voluntary blood donation nurtures unity amongst a community, nation, and humanity as a whole. People with good health gather their efforts and energy to support and donate blood to those who need it. It is estimated that more than 100 million units of blood are donated annually worldwide (Myers and Collins, 2024). The continuous availability of a variety of blood types and their components is collected, tested for their quality, processed, stored, and distributed safely in blood banks. These procedures are regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for hospital use (UK Government, 2023). It also minimizes the chances of delay of blood transfusions, especially during acute blood loss, where necessary life-saving surgical procedures are needed. Blood transfusions are also required for trauma care, cancer, and routine management of chronic illnesses (Myers and Collins, 2024; Talawar, Havanoor, and Kamatad, 2024). This lowers the risk of accident-related and perioperative mortality rates (Makowicz et al., 2022).

Blood transfusions have a therapeutic function in treating blood disorders that have an abnormality in the count of red blood cells (erythrocytes). Erythrocytes carry oxygen around the body. It contains a red pigment called haemoglobin that binds with oxygen. Anaemia is a condition characterised by low red blood cell count, whereas Polycythemia vera and other myeloproliferative disorders are associated with high red blood cell production (Myers and Collins, 2024; Makowicz et al., 2022). Rare blood conditions such as hereditary haemochromatosis are attributed to the abnormal production, storage, and distribution of iron.

Other conditions where blood transfusion is required are to decrease mortality rates in infections such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which is the main causal factor for Acquired Immune Deficiency Disease (AIDs). Malaria and maternal-related conditions are other examples.

Sometimes blood collected cannot be used in a transfusion and instead is used to develop treatments, research, and training, diagnosis (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025a).

Researchers have discovered alternative ways to meet the demand for blood availability by developing artificial blood using non-blood oxygen carriers. For instance, perfluorocarbon compounds, non-human haemoglobin, human haemoglobin, and in vitro-produced erythrocytes.

One of the current challenges is the continuity in promoting the importance of blood donations to meet the demands achieved through education and raising awareness. On a societal level, the number of donors and their understanding of the advantages and importance of donating blood is considerably important for the younger generation. There are reports that they are the major age group that donates blood (Makowicz et al., 2022).

The factors that affect blood donations include several perspectives: individual, systemic, level of donor care, and the COVID-19 pandemic. On an individual level, the health and well-being of volunteer donors are vital, especially their perception when donating, frequency of donating, and type of blood products donated (Thorpe et al., 2022). Fear of pain, weakness, and adverse effects contributes to their reluctance to donate. Fear of needles (trypanophobia) was discovered to be the main reason, and this was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, where quarantine and other procedures were organised to limit the spread of coronavirus (Talawar, Havanoor, and Kamatad, 2024). Some patients have misconceptions about their eligibility to donate blood. They consider that they cannot donate due to their prescribed medications, dietary habits, and minor health issues (Talawar, Havanoor, and Kamatad, 2024).

On a systemic level, location, busy schedules, transportation, and accessibility could contribute to the challenges of donating blood (Talawar, Havanoor, Kamatad, 2024). Moreover, three key elements influence the clinical outcomes of donor care: education, reassurance, and experience. Having clear information, surrounded by supportive staff in a less intimidating atmosphere, can encourage donors to donate blood more than once (Talawar, Havanoor, and Kamatad, 2024).

Understanding deterents and developing strategies to encourage donations and boost management of the blood supply is paramount. Charities such as Blood and NHS Blood and Transplant, and policymakers, conduct significant social campaigns through public education and correct misconceptions. They also set up blood centres at multiple national sites. This will help encourage repeat blood donations and increase accessibility to maintain the demand for the blood resource (Talawar, Havanoor, and Kamatad, 2024).

This article aims to give an insight into the role of blood in the human body, the difference between organ and blood donation, ways in which blood is donated, and factors that affect blood donations.

What Is The Function Of The Blood And Its Composition

The average human adult has more than five litres of blood in the body. It transports oxygen and nutrients via the circulatory system to cells and tissues and removes waste products (Dean, 2005). During exercise, the heart works harder to provide more blood at a faster rate and meet the oxygen demand of the muscles (Dean, 2005).

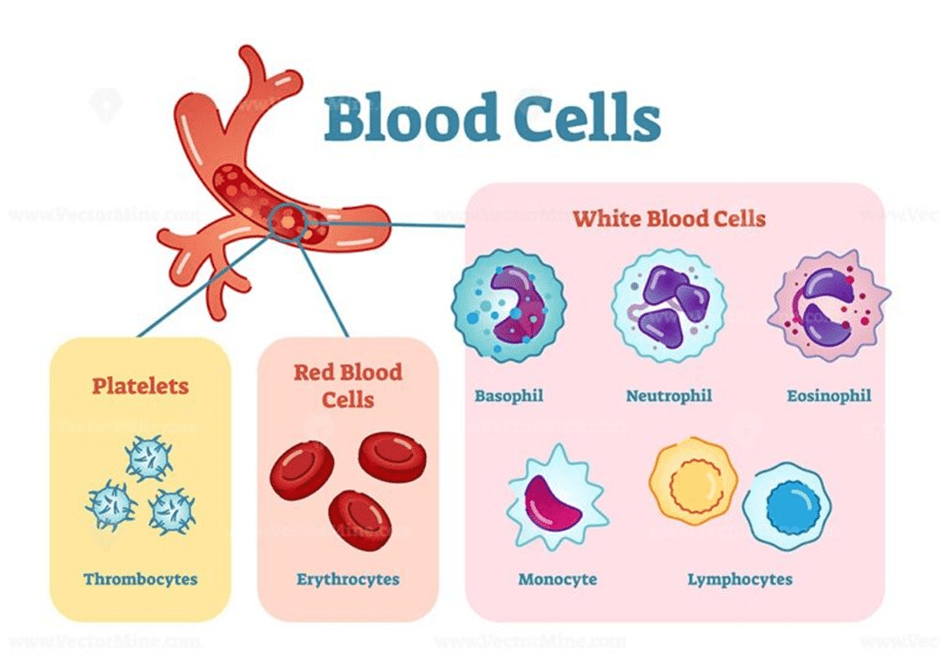

The blood is a mixture of cellular components and proteins suspended in a fluid called plasma. The three main proteins are: globulins, fibrinogen, and albumins. Globulins are part of the immune system that form immunoglobulins, also referred to as antibodies, which travel to the site of infection alongside immune cells, where they accumulate and fight infection (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006; NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025b; Dean, 2005). Fibrinogen functions in blood clotting to avoid blood loss. Albumins maintain plasma volume and help transport hormones (thyroxine), free fatty acids, which are essential for energy metabolism. It also transports the breakdown product of haemoglobin, Bilirubin, to the liver. The three components discussed are: red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes). Please see Figure 1.

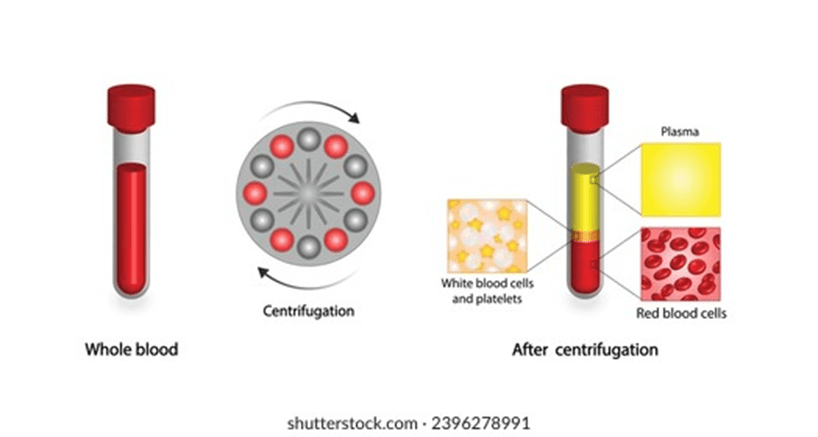

Centrifugation is the process in which blood samples are positioned in a balanced way and spun at high speed. They are divided into compartments based on their density using centrifugal force. Please see Figure 2. The aim is to maximise the utility of one whole blood unit (Baso and Kulkarni, 2014). The plasma, erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes have specific temperature and storage conditions to maintain therapeutic efficacy (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014).

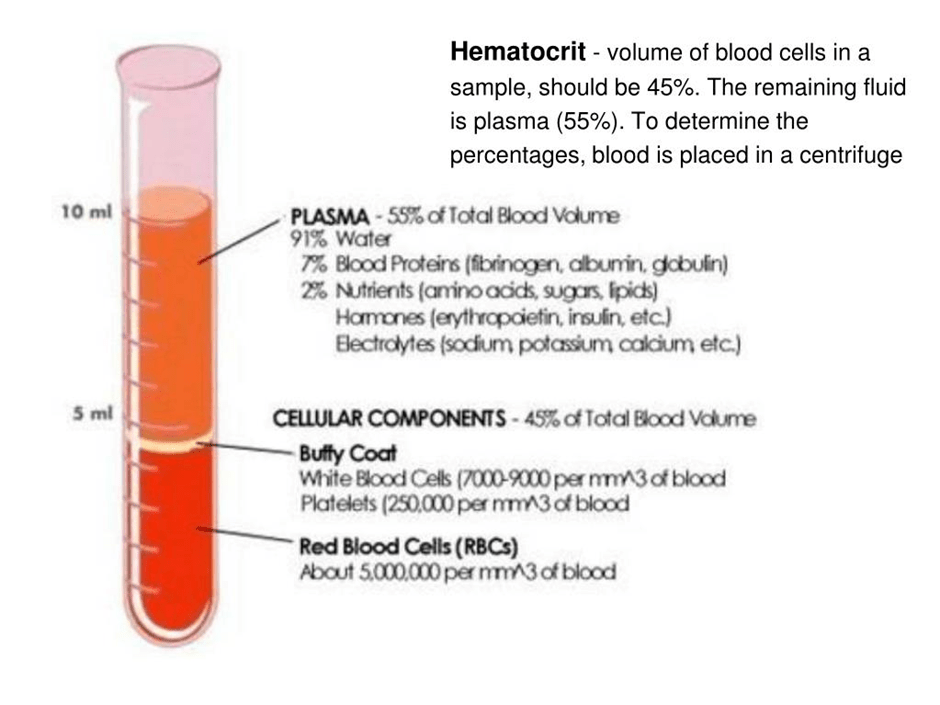

The plasma is a straw-coloured liquid that accounts for ca. 55% of the blood. Some sources suggest it forms 60% of the blood (Dean, 2005). Please see Figure 3. Plasma mainly consists of water (91%), proteins (7%), and nutrients (2%). The centre is the white buffy coat that contains white blood cells and platelets (Dean, 2005). The bottom layer consists of erythrocytes. The middle and bottom layers form 40% of the blood (Dean, 2005). Other sources suggest 45% of the blood. Most of the 45% consists of red blood cells, and <1% consists of white blood cells and platelets.

Figure 3: The different compartments of the blood post-centrifugation.

Erythrocytes

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) carry oxygen around the body via the blood. They contain a red pigment called haemoglobin made of iron (haem) and protein. The haemoglobin molecule associates with oxygen via the iron atoms present in its structure. The approximate diameter of red blood cells is 8 micrometres (μm) (Clemons, 2024). Other sources suggest 6μm (Dean, 2005). An adult has ca. 20 to 30 trillion erythrocytes, which is approximately a quarter of all human cells (Biology Insights, 2025). This highlights their viral impact in maintaining energy through delivering oxygen to cells and tissues.

Erythrocytes are adapted to their function by having a biconcave, flat, donut-like shape to increase the surface area. This ensures there is efficiency and flexibility when collecting and transporting oxygen through the blood capillary system (Biology Insights, 2025). Their surface area is further increased as they lack a nucleus, mitochondria, and ribosomes. This provides more space for haemoglobin to transport oxygen. The lack of a nucleus suggests they are unable to either divide or produce new proteins, which commonly occurs in the ribosomes. Thus, this limits their lifespan (Biology Insights, 2025). In non-mammalian vertebrates such as birds and fish, mature red blood cells do have a nucleus (Dean, 2005). This suggests there is variation in the structure of red blood cells across vertebrates.

It is estimated that two to three million new erythrocytes are produced every second in the red bone marrow. The red bone marrow is the soft tissue present inside the bones. Erythrocytes are then released in small blood vessels called capillaries and into the circulation (Dean, 2005; Clemons, 2024). The development and growth of erythrocytes is regulated by a hormone called erythropoietin, which is secreted in the kidneys. The approximate lifespan of erythrocytes is 110 to 120 days (Clemons, 2024). After the lifespan, two to three million old erythrocytes are broken down per second, and they are removed by macrophages and ingested into the spleen and liver (Dean, 2005). Dead erythrocytes are broken down into haem (iron) and globin (protein). Iron is recycled and transported back to the red bone marrow to produce new red blood cells (Clemons, 2024). Globin is hydrolysed into amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, to produce new proteins. This suggests that when someone donates blood, the stores are replenished quickly.

Leukocytes

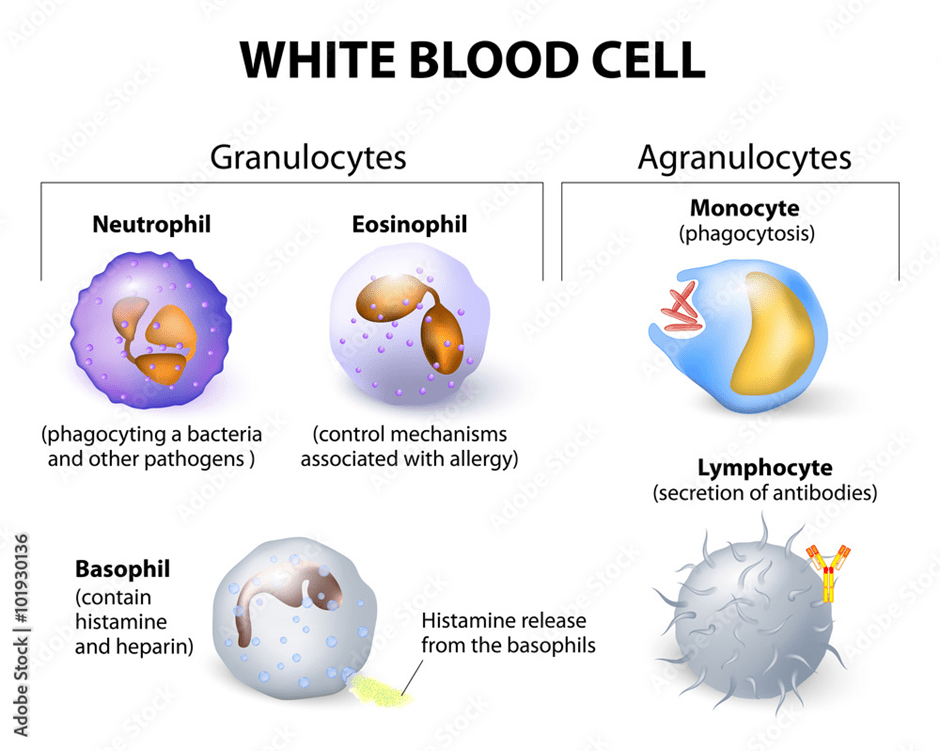

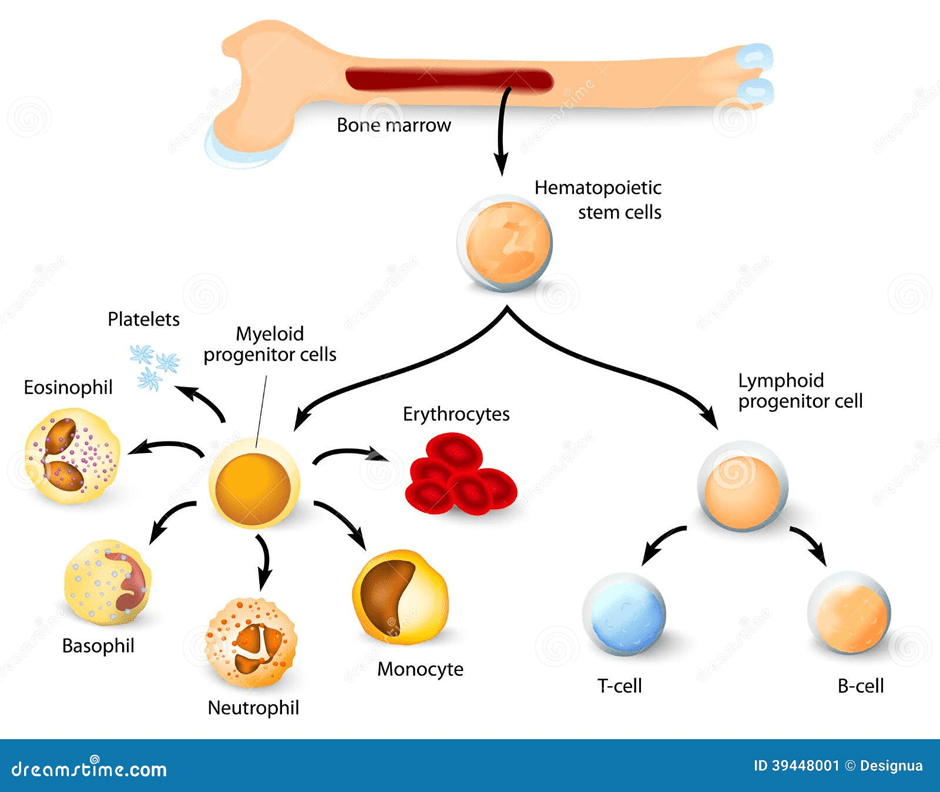

Leukocytes function in protecting the body from infection. They are classified based on their structure: shape and size (Dean, 2005). The three types are: Polymorphonuclear granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes. Please see Figure 5. They are produced in the bone marrow; however, monocytes and lymphocytes undergo further development in secondary lymphoid organs like the thymus. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes have multilobed nuclei (multiple lobes) and membrane-bound granules in their cytoplasm that vary in colour dye. Eosinophils (red dye), basophils (basic dye), and neutrophils (Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006). Other leukocytes have a large, round nucleus, for instance, lymphocytes. Monocytes are larger than granulocytes and have a horseshoe-shaped nucleus.

Polymorphonuclear granulocytes

Eosinophils are released as part of an allergy response. Similarly, basophils has a role in allergic reactions, where they release a chemical called histamine. As a result, white blood cells leave the blood by squeezing through pores in the blood vessel and migrate to the site, and initiate a healing process. Neutrophils have an irregularly shaped nucleus and many lobes. Their granules contain enzymes that help digest pathogens (Dean, 2005).

Lymphocytes

They have a single, large, round nucleus. They are divided into B cells and T cells, which differ in the location where they become mature and their type of immune response. B cells, also known as plasma cells, mature in the bone marrow. They produce proteins, called antibodies, which specifically recognise a protein called an antigen on the surface of pathogens. They are then able to neutralise and inactivate the pathogen. Alternatively, T cells mature in the thymus. There are two main types: T killer and T helper cells. T killer cells have a cytotoxic role in killing infected cells, whereas T helper cells coordinate and recruit other immune cells (Dean, 2005).

Monocytes and Macrophages

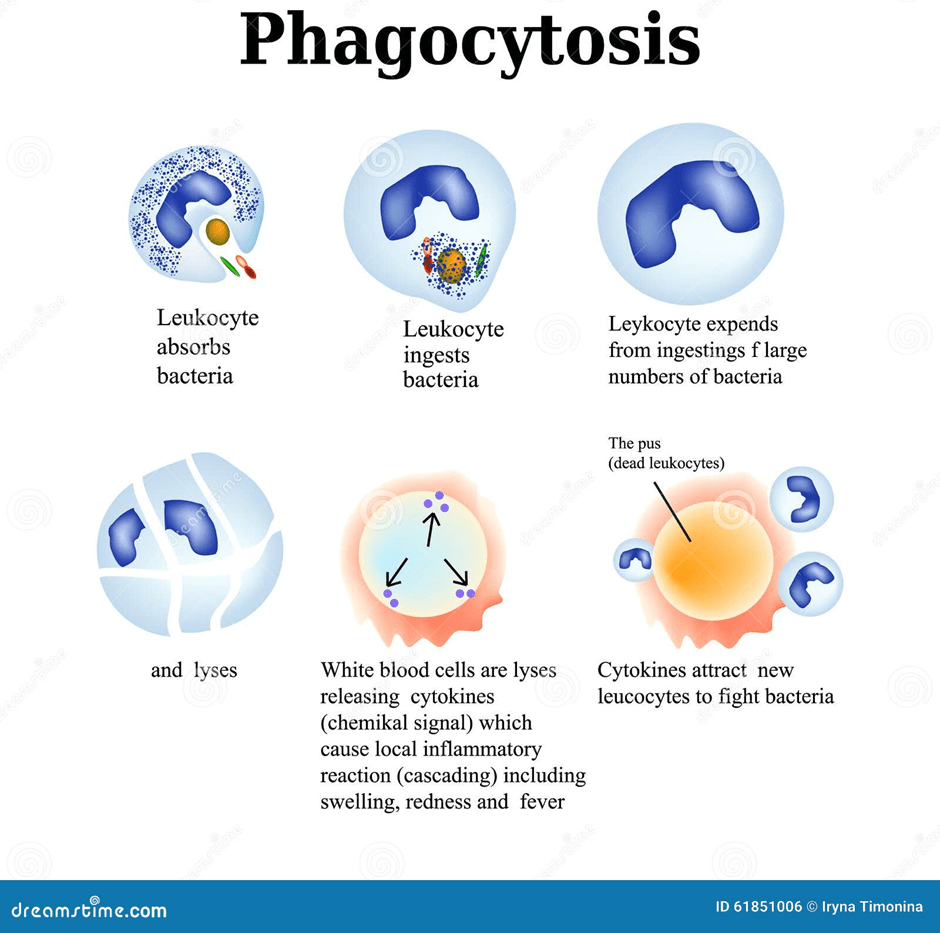

Monocytes are small leukocytes that circulate in the blood. They differentiate and develop into macrophages when migrating into tissue. Macrophages are antigen-presenting cells that trigger an immune response. They receive a signal when there is a damaged part in the body. An example is interleukin (IL-1) secreted by macrophages, which can give rise to fever. They are amongst the primary immediate defences where they engulf and digest pathogens without specificity via the enzymes present before other white blood cells reach them (Dean, 2005). This process is called phagocytosis, please see Figure 6. There are different types of macrophages. Kupffer cells in the liver remove remaining harmful substances from the blood. Alveolar macrophages present in the air sacs in the lungs remove harmful objects inhaled. Macrophages in the spleen remove damaged or old erythrocytes and platelets from the blood circulation.

Platelets

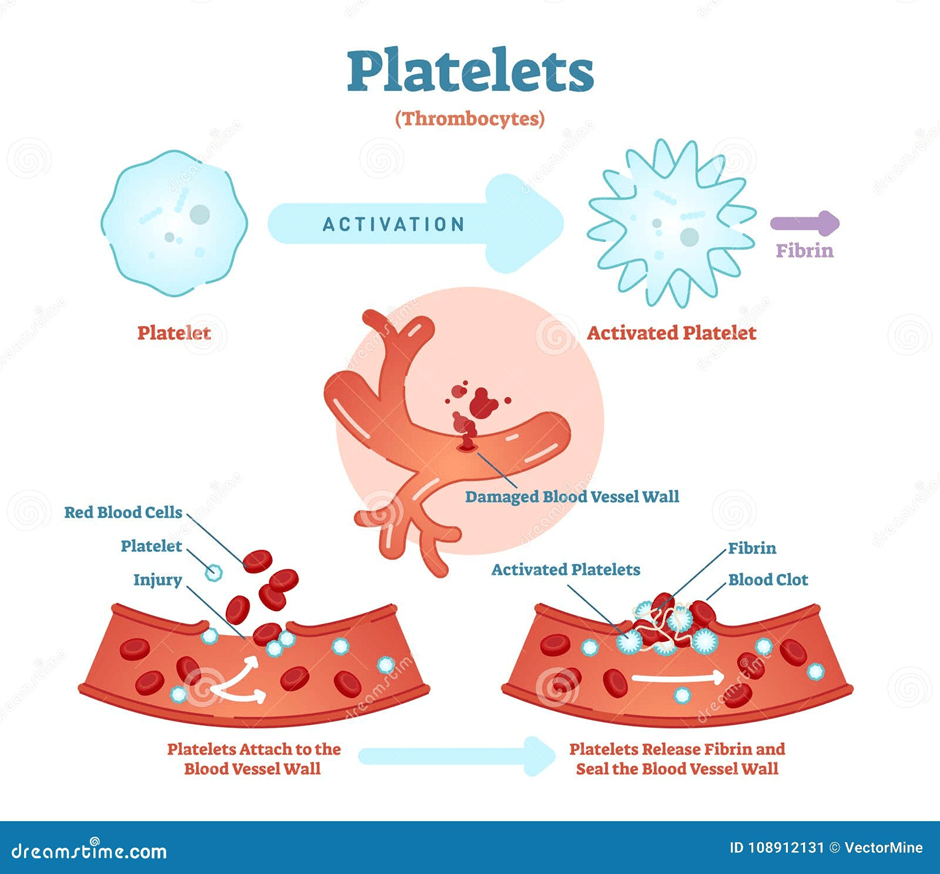

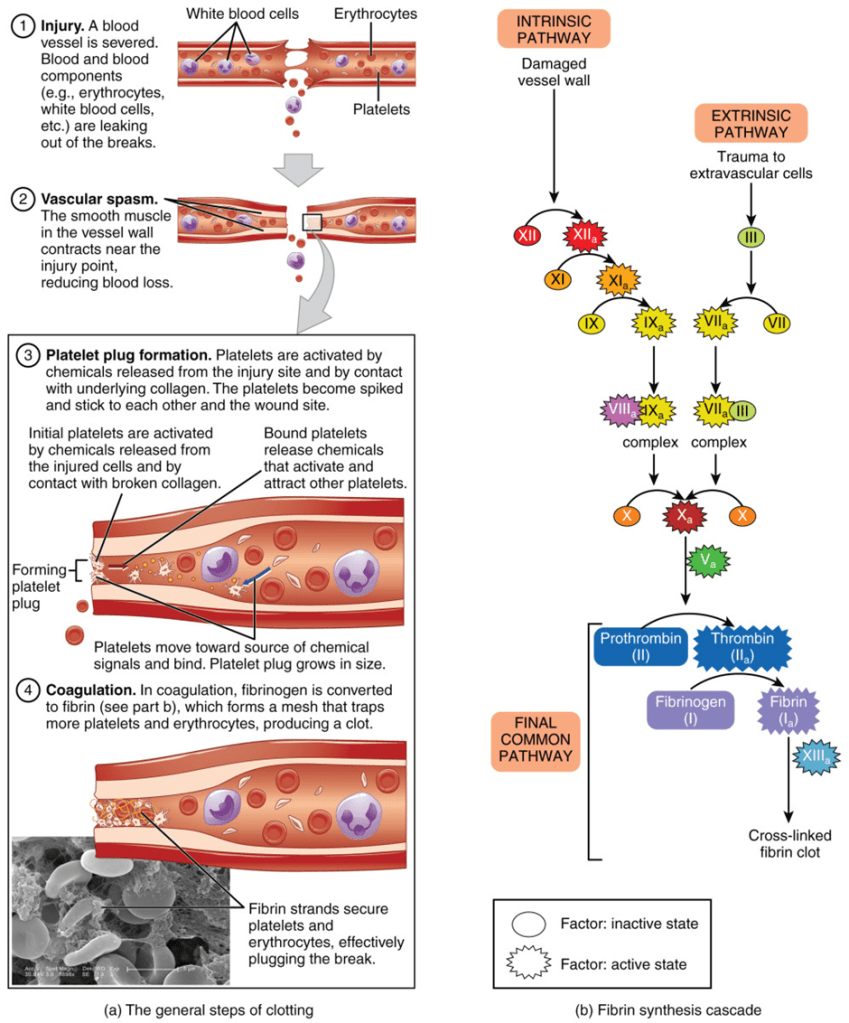

Platelets are noncellular, irregularly shaped fragments and are smaller than erythrocytes. They originate in stem cells present in the bone marrow that develop into precursors called megakaryocytes. Mature platelets circulate in the blood for 9 days and are removed by the spleen by the end of their circulation. One cubic millimeter of blood contains between 150,000 and 400,000 platelets (Dean, 2005). Their role is to clot the blood to reduce excessive bleeding. They form a coagulation plug where many platelets block the damaged blood vessel (Dean, 2005). Please see Figure 7. A solid gel called a thrombus or clot, which contains a protein called fibrin, is formed (Widmaier, Raff and Strang, 2006). Fibrin is the activated form of fibrinogen.

The Difference Between Blood And Organ Donation

Organ donation is the process by which some or all of the donor’s organs and tissues are given to patients whose organs are not functioning properly. The donors are registered on the NHS Organ Donor list (DKMS Foundation, 2018). There are two types: living organ donation, where some organs are donated while the donor is alive. Most organ and tissue donations come from those who have passed away (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025c). Common organs that are donated are the heart, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and small bowel. Tissue like skin, bone, heart valves, and corneas are donated to help patients who need them (County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, n.d). More than 8000 people in the UK need an organ transplant, and each year, 400 people pass away while waiting for a suitable donor organ.

On the other hand, blood donations take place in the form of blood, plasma, bone marrow, and stem cells. Blood donations are received by hospitals for patients during emergencies and those who have conditions like blood cancers. Blood donors are registered via health authorities in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland (DKMS Foundation, 2018).

Stem cells are undifferentiated cells that are used in growth and repair. Please see Figure 8. Most people (90%) donate their stem cells from the blood by a process called PBSC collection to treat blood cancers and blood disorders. They are matched based on the patient’s and donor’s human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and type of tissue. The more people on the blood, organ, and stem cell registry, the higher the chances for matches to occur and save lives. The remaining 10% is bone marrow, the soft tissue in the bone, which is commonly extracted from the hip bone (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025c).

How Is Organ Donation Different From Blood Donation? By Everyday Bioethics Expert

Types of Blood Transfusions

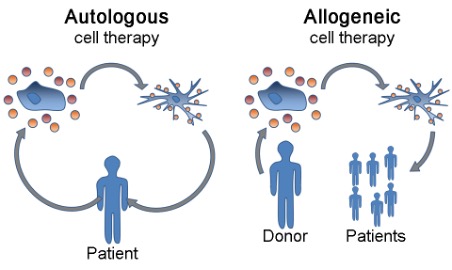

There are two main types of blood transfusions: autologous and allogeneic. Autologous blood transfusion is when blood or its components is collected and transfused back to the same patient. On the other hand, allogeneic transfusion is when blood is transferred from compatible donor to patient as presented in Figure 9 (Sam et al., 2023).

Allogenic Blood Transfusion

Blood Typing

The initial blood typing procedure, as standard practice, originated in the early 20th century (Lee, 1917). The first blood system identified was the ABO by Karl Landsteiner. However, there were several limitations: preventing contamination when collecting blood. There was no ambient temperature nor storage conditions optimised for the blood. Thus, blood was directly donated from donor to patient with immediate effect (Myers and Collins, 2024). This technique was effective on a small scale as donors were locally available. On the other hand, this had an adverse effect as soldiers in World War I succumbed to their non-fatal wounds because blood transfusions were not delivered promptly (Myers and Collins, 2024).

To overcome this limitation, a method was developed to meet the demands of war injuries. Citrate was added to the donor’s blood to prevent clotting (Lewisohn, 1958). Another method was attempted by Captain Oswald Hope Robertson of the US Army Medical Corps, who tried adding group O blood to glucose to maintain the viability of erythrocytes for several weeks when refrigerated (Wang, 2018; Rous and Turner, 1916; Robertson, 1918). This helped to separate donors from patients, independent of time and location. The two systems used by healthcare professionals to determine blood type and compatibility are the ABO and Rh systems. HLA system for stem cell transplant in patients with bleeding disorders.

The ABO system

The ABO system aimed to classify blood based on the presence or absence of antigen proteins and carbohydrates on the surface of erythrocytes. Antigens are markers that trigger an immune response to foreign substances such as viruses, bacteria, or incompatible blood that can lead to a severe immune reaction. Antibodies induce an immune response by targeting and binding to antigens of foreign substances. Each type of blood has specific antibodies in the blood plasma that correspond to antigens on the surface of erythrocytes.

However, there should be no antigens nor antibodies in the donor’s or patient’s blood to cause a transfusion reaction (Giri, 2019). This is why it is important to do a pretransfusion compatibility test to prevent effects after transfusion.

Pretransfusion compatibility testing

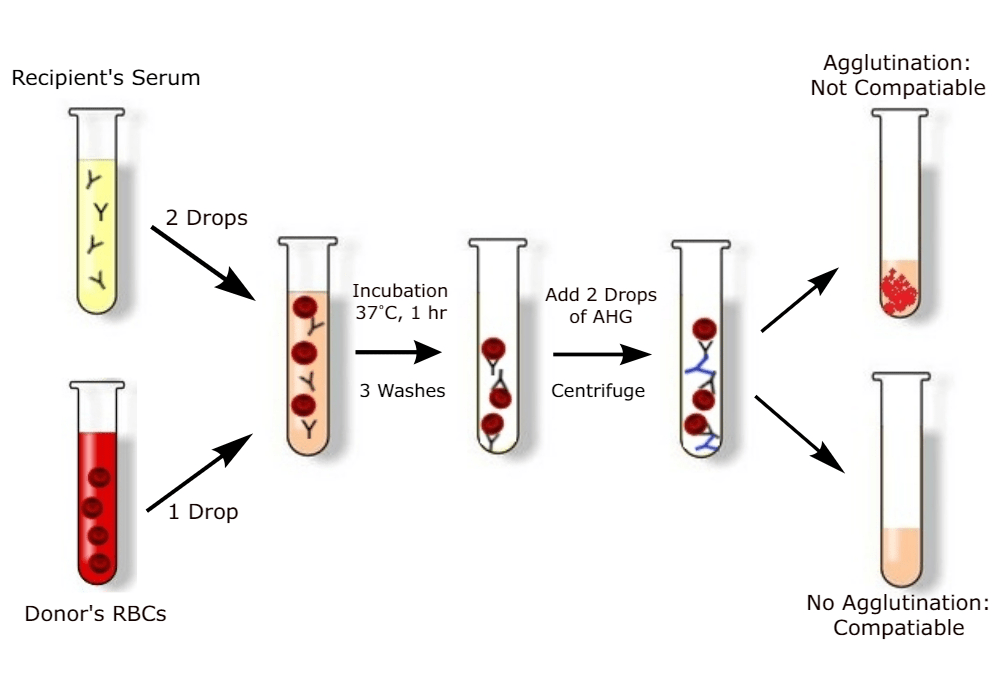

To test for compatibility by cross-matching donor and recipient, there are two cross-matches. In a major cross-match, presented in Figure 10, the recipient serum is added to the glass slide with prospective donor erythrocytes. This is to determine the presence of antibodies that may rupture or cause clumping (agglutination) of erythrocytes. If this occurs, it is a MISMATCH and can cause serious reactions (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

On the contrary, in a minor cross-match, the donor’s serum or plasma is added to the patient’s erythrocytes. This is to determine the presence of the antibody that may cause haemolysis (breakdown of red blood cells) (Giri, 2019). The incompatibility results for the major cross-match are more significant than the minor cross-match. In the minor cross-match, the serum of the donor that contains the antibodies is more diluted in the patient’s plasma. Conversely, in a major cross-match, the patient’s plasma containing antibodies is more concentrated and can destroy the donor’s red blood cells (Giri, 2019).

The ABO classification system

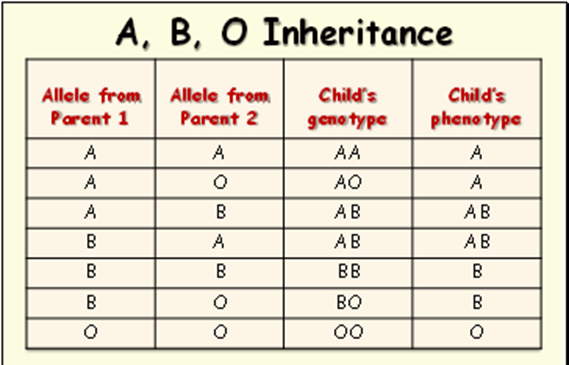

The ABO system is presented in Figure 11 (Unknown, 2025). The gene for antigen A and the gene for antigen B are codominant. Both traits are expressed when the gene for A is from one parent and the gene for B from the other parent.

- Type A blood. The anti-B antibodies attach to A antigens in type A blood. It can attach to B antigens if type B or AB blood is introduced.

- Type B blood –The anti-A antibodies can bind to antigen B. It can also attach A antigens if type A or AB is introduced.

- Type AB blood – No anti-A or anti-B antibodies in the plasma. People with AB blood can receive blood from any universal recipient.

- Type O blood – No A or B antigen in the RBC, but has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies in the plasma. People with type O blood can only receive their own, but they can donate any blood type (universal donors).

The child’s predicted blood type is illustrated in Table 1. The genotype is the genetic code or expression inherited from the parents, whereas the phenotype is the physical appearance of a trait. For example, both parents had A; the child’s genotype is AA because they obtained a gene from each parent. Upon testing for the blood type, the result would reveal that the child has blood type A. Similarly, the outcome will be the same even if one parent had A and the other had O. The O is not dominant and is a universal donor with neither A nor B antigens on the erythrocytes.

The Rh system

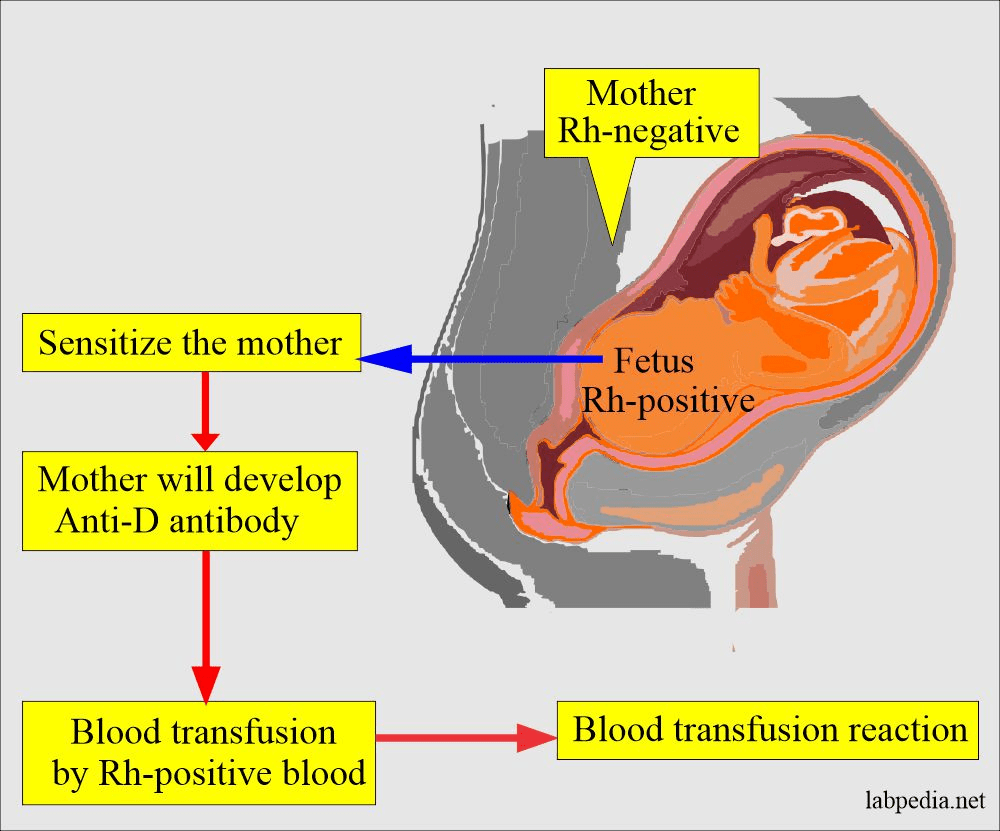

The Rh factor was first studied in rhesus monkeys as a model for experimental purposes. During pregnancy, some of the fetal erythrocytes cross the placental barrier into the maternal circulation. If the mother is Rh-negative and the fetus is Rh-positive, the mother produces anti-Rh antibodies. This mainly occurs during the separation of the placenta at delivery (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006). Please see Figure 12. The Rh-positive pregnancy rarely causes danger to the fetus because delivery happens before the mother makes the antibodies (Widmaier, Raff, and Strang, 2006).

Rh positive (Rh+): Rh positive/Rh negative blood – It has the Rh factor Rh D antigen.

Rh negative (Rh-): It does not have the Rh factor Rh D antigen. If Rh-positive blood is received, it can produce antibodies against or reject.

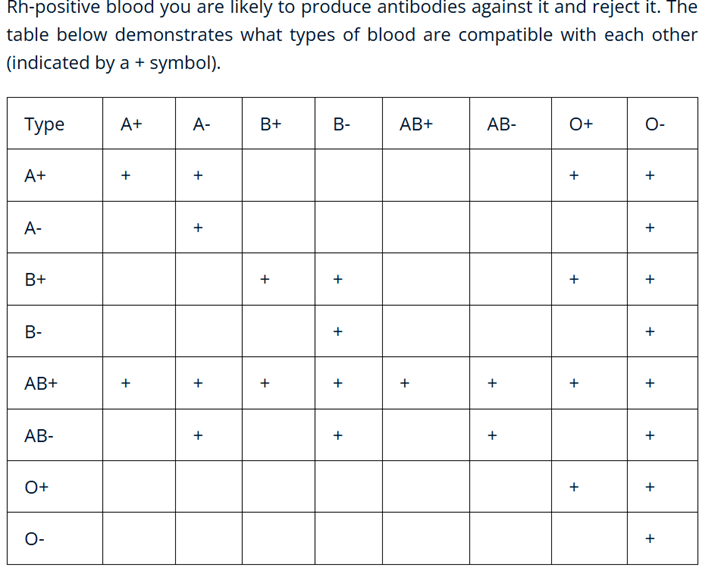

Table 2 presents the types of blood that are compatible with each other based on the Rh system. If both types have A+, then there is compatibility; however, if one has A- and the other has B+, then there is no compatibility.

For further information on the Rh system, please visit: https://www.blood.co.uk/why-give-blood/demand-for-different-blood-types/the-rh-system/

The HLA system

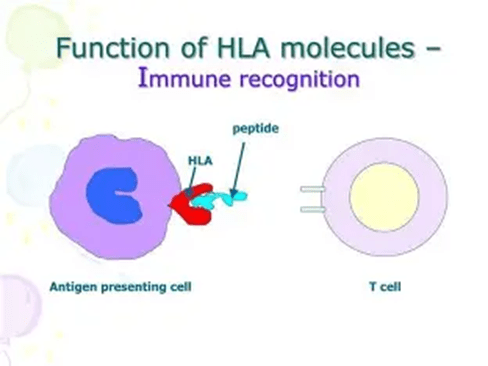

The donation of stem cells (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) depends on the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and the type of tissue. The HLA are proteins found on the surface of most cells, as illustrated in Figure 13. It helps the immune system to identify cells that belong to the body, and there are 12 distinct HLA markers, creating multiple possibilities. HLA matching is vital to achieve successful outcomes from transplantation, allowing the donor cells to engraft (donated cells) and produce new blood cells in the body, especially if the bone marrow of the patient is malfunctioning and unable to produce efficient blood cells. This lowers the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which commonly arises when the immune cells from the donor (graft) attack the cells present in the patient (host) (National Marrow Donor Program, 2025).

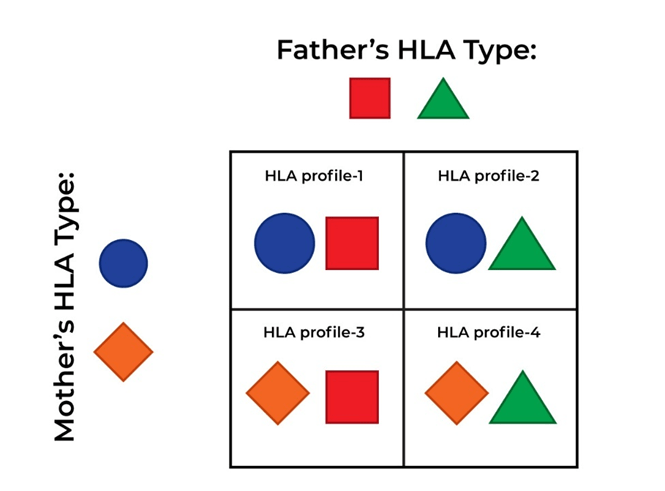

To identify an HLA type, a blood sample or a cheek swab is examined. The patient’s results will be compared with those of the patient’s relatives, who may be asked for their HLA type to find a donor match. HLA is inherited, and a parent or child can be a potential donor, as half of their DNA is obtained from either parent. Please see Figure 14. There is a 1 in 4 chance that a sibling who shares the same parents may be a full HLA match. However, immediate members are less likely to be a fully matched donor; there is 70% of being incompatible (National Marrow Donor Program, 2025). Other potential HLA matches could be someone from the same ethnic background (National Marrow Donor Program, 2025).

There are three outcomes retrieved from HLA typing: full, partial, and haploidentical. A full HLA match is when both the donor and recipient have identical HLA markers. A partial HLA match happens when the HLA typing of the donor has high similarity to the patient’s HLA. Haploidentical, which commonly arises if the donor is the parent or child, where half of the HLA (50%) is the same (National Marrow Donor Program, 2025).

To overcome the limitation of finding a full HLA match for all patients, advancements were made to maximise chances of HLA typing for unrelated donors or where the donor has a single-allele mismatch (9/10) (Park and Seo, 2012). This is dependent on the underlying diagnosis. There was a higher risk of mortality for low-risk patients who were diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) within two years than high-risk patients who experienced no effect on survival despite their advanced stage in CML, acute leukaemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome (Petersdorf et al., 2004). The death rate is associated with the longer time interval from diagnosis to transplantation and finding a donor. Therefore, the successive rate of potential HLA matching is directly proportional to advanced disease.

The transformation of the method used to detect anti-HLA antibodies from complement-dependent microlymphocytotoxicity to solid-phase assay has helped to examine the relationship between donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies (DSHA) class I and II in organ rejection of allogenic HSCT, especially in patients undergoing haploidentical HSCT (Spellman et al., 2010; Ciurea et al., 2009). A possible explanation could be the expression of similar HLA antigens on hematopoietic stem cells. This critically demonstrates the importance of finding DSHA in the recipients when there is a limited or a lack of full HLA matching (Focosi, Zucca, and Scatena, 2011). Methods such as plasma pheresis and immunoadsorption can lower the sensitivity of patients who have no alternative donor (Park and Seo, 2012). Plasma pheresis is the exchange of plasma and its components between the patient and donor.

Health Promotion is critical in raising the awareness on the importance of donating blood. This can be achieved through posters, leaflets, TV, social media and events. For more poster, material, please visit

https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/how-you-can-help/get-involved/download-digital-materials/

Why is it important to donate blood?

Donating blood is important when treating patients with cancer, gastrointestinal bleeding (abdomen/belly), bleeding disorders, maternity, and other conditions. The transfusion of red blood cells is often used during surgical procedures involving injuries and childbirth. It is estimated that two-thirds of the blood in England are used in the treatment of medical diseases, the remaining third are applied in surgery and childbirth (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025a). Transfusion of platelets and plasma is commonly given when there is excessive bleeding and bruising from the injuries. Transfusion of white blood cells is routinely used to treat leukaemia, a cancer where there is abnormal growth of white blood cells, giving rise to infections. Please see Figure 15. A child who may have chickenpox has high levels of antibodies in their plasma. Therefore, if a patient with leukaemia has been exposed to chickenpox, it can prevent potentially life-threatening diseases. This suggests there is a beneficial purpose for each part of the blood.

It is estimated that 13% of the time, hospitals request O-negative blood, but only 8% of the donors have this blood type. This highlights the demand of particular blood types, especially O-negative, as their blood can be utilised in emergencies and when the blood type is unknown. Another blood type that is also essential but is rare is the Ro subtype. It is estimated that 2% of donors have this subtype, which is a variation of Rh-positive. It is compatible with A, B, AB, and O subtypes. There is an increase of this subtype by 10-15% annually. Some blood types are more common in particular communities, for example, BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) communities. This highlights the size of the gap between the blood donors and the amount the hospital needs for ongoing transfusions to avoid waste and meet the limited shelf life (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025d).

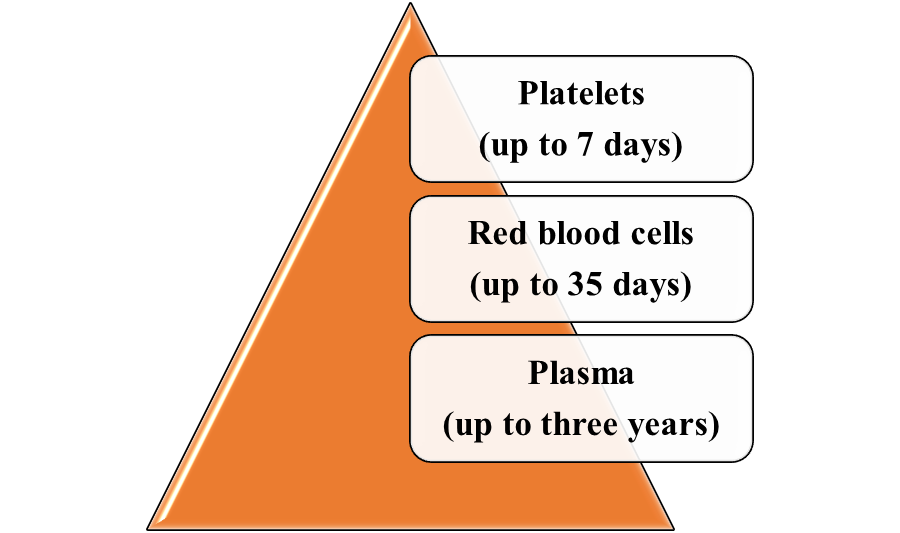

According to the NHS Blood and Transplant (2025d), the shelf life of the blood components are as follows:

Donating red blood cells

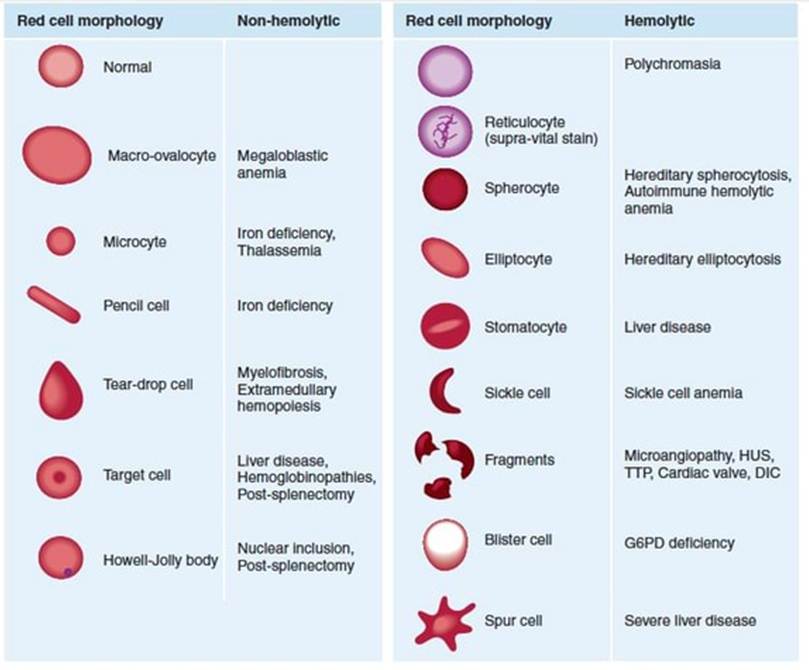

Amongst the classifications of anaemia is the differentiation between haemolytic and non-haemolytic anaemia. Haemolysis is the destruction of red blood cells. There are distinctive shapes (morphology) of the erythrocytes as presented in Figure 17. An example of non-haemolytic anaemia is megaloblastic anaemia, characterised by the presence of large oval-shaped erythrocytes (macro-ovalocytes). This condition is caused by the delayed maturation of erythroblasts (immature or early red blood cells) (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003). As presented in Figure 18, the erythrocytes appear large, and the neutrophils have nuclei with a minimum of six segmented lobes. This is two-fold higher than typical neutrophils, which have three segmented nuclear lobes. The lobes are connected by tapering chromatin strands in both normal and hypersegmented neutrophils.

Sickle cell anaemia is an example of a haemolytic anaemia. The morphology of the erythrocytes is sickle-shaped or crescent-shaped. The transformation from a biconcave shape to a sickle crescent shape is a result of a genetic disorder in the haemoglobin sickle gene (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003). There is a substitution of one amino acid, valine, for glutamic acid on position 6 in the beta globin chain. The haemoglobin has four globin chains, two are alpha and the other two are beta. There is relative resistance to malaria. The crescent-shaped erythrocytes limit the blood flow due to their minimal flexibility. This causes blockage and increased pressure to meet the oxygen demand (Biology Insights, 2025).

Normocytic anaemia

Another classification system of anaemia is by the volume and size of the red blood cells, as presented in Figure 19. The normal volume of erythrocytes is 80 to 96 femtolitres (fl). This is referred to as normocytic anaemia. Common causes of this form of anaemia are chronic diseases and conditions. Patients with chronic kidney failure and liver disease are at risk. Patients with chronic infections like tuberculosis and infective endocarditis, and inflammatory bowel diseases that can affect the intestines, like Crohn’s disease, commonly have normocytic anaemia. Crohn’s disease, pictured in Figure 20, is a progressive chronic disease. The T cells increase the production of proinflammatory mediators such as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and interferon gamma, but decreases the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin 4 (IL-4) and 10 (IL-10) (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003). This can cause cellular damage, especially in the ileocaecal region, between the last segment of the small intestine (ileum) and the first segment of the large intestine (caecum). Patients with Crohn’s disease have a cobblestone appearance on the mucosa.

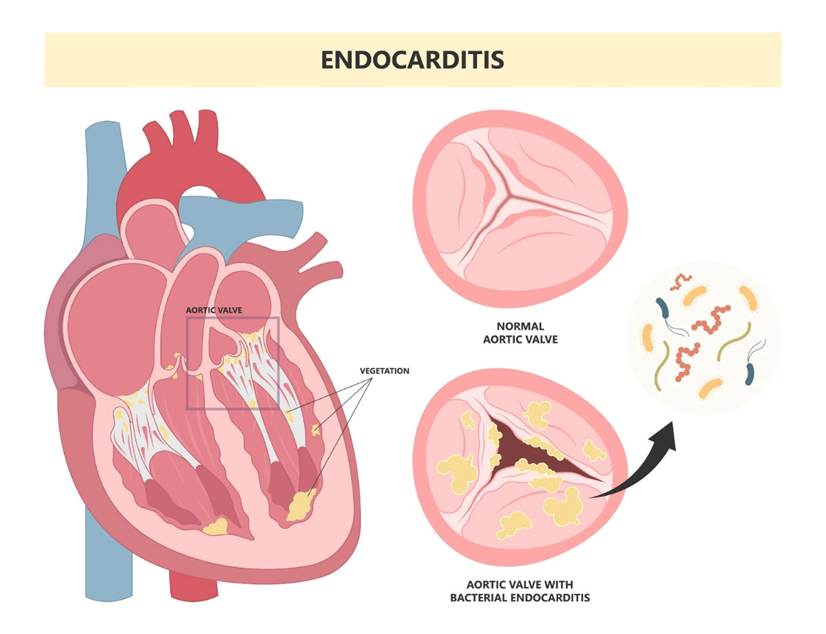

Endocarditis is the infection of the endocardium of the heart, particularly the valves; flaps of tissues between chambers and vessels to prevent backflow of blood. Please see Figure 21. It is caused by multiple bacterial species. Streptoccocus mutans is part of the normal flora of the respiratory tract but can affect the blood, causing bacteraemia where the bacterium enters the blood. It is a result of removing tonsils (tonsillectomy), tooth extraction, and complications of bronchoscopy (a thin tube examining the branches of the lungs). Another example is Staphylococcus that occurs in unhygienic shared needles by drug addicts and as a complication in patients with central venous lines (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003).

Figure 21 A visual presentation of endocarditis characterised by the valves infected with bacteria (Cardiology Master, 2025)

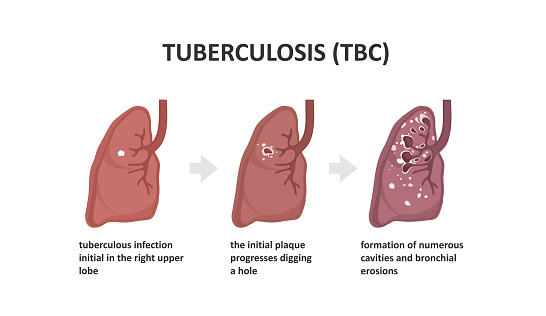

Tuberculosis is an infection caused by the bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it affects the lungs and can progress to the gastrointestinal tract, in the ileocaecal region. Please see Figure 22. There is infiltration of neutrophils, which are replaced by macrophages to engulf the bacilli bacteria. As a consequence, granulomas containing caesous lesions or turbecles are synthesised in the lymph nodes, especially the mediastinal and cervical regions (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003). Tuberculosis is characterised by the presence of Langhan’s giant cells and epitheloid cells with a horse shoe pattern of the nuclei; please see Figure 23 (AG, 2014).

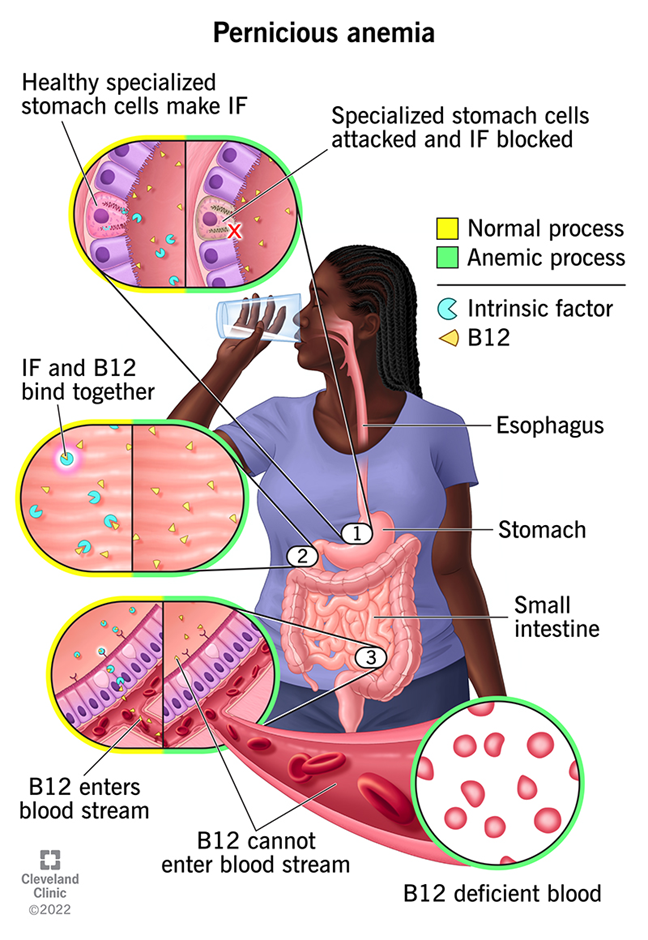

Myelodysplasia (immature blood cells), megablastic and pernicious anaemia are other causes of normocytic anaemia. Pernicious anaemia is an autoimmune condition where there is a lack of absorption of Vitamin B12 and low production of intrinsic factor as a result of the breakdown of the gastric mucosa lining. Please see Figure 24.

Microcytic anaemia

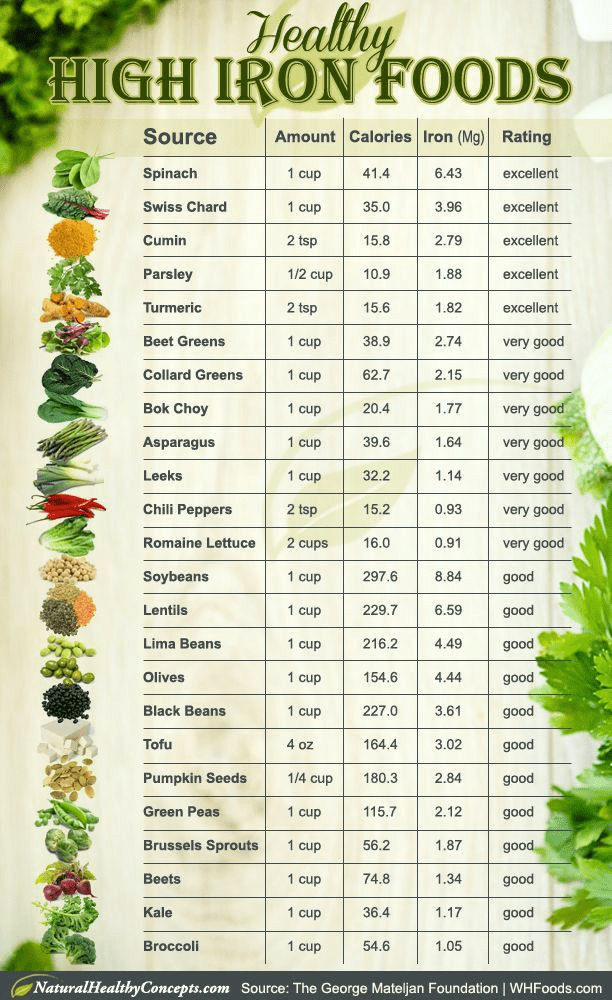

As presented in Figure 19, low red blood cell and haemoglobin count is microcytic anaemia. The most common cause is iron deficiency, as most of the iron is found in haemoglobin. The remainder is stored as ferritin and haemosiderin in the skeletal muscle, liver, and reticuloendothelial macrophages (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003). About 1mg of iron is lost as sweat, faeces, and urine. Women tend to lose more iron during menstruation and the pre-menopausal stages.

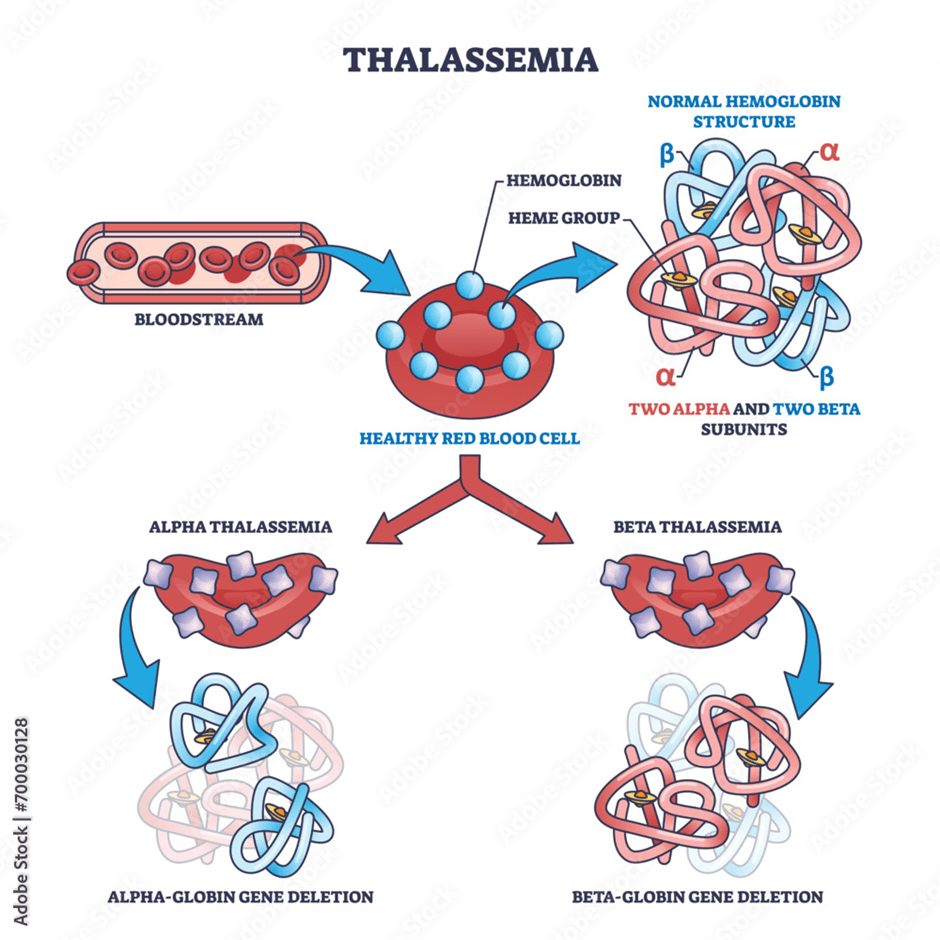

Other common causes of microcytic anaemia are thalassaemia and sideroblastic anaemia. Thalassaemia is a genetic disorder where there is a mutation (change in the gene) in the production of the protein (globin) of haemoglobin. The haemoglobin molecule is made of four globin chains: Two alpha and two beta chains. Both parents need to have the genetic mutation for the child to have this condition via prenatal diagnosis, please see Figure 25. This is referred to as thalassaemia major. Alpha thalassaemia arises when the alpha chain is mutated, whereas beta thalassaemia arises when there is a mutation in the beta globin chain. Other symptoms that may arise in response to the abnormal structure and production of haemoglobin is enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) and abnormal bone marrow (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003).

Sideroblastic anaemia, pictured in Figure 26, arises when there are abnormal ringed sideroblasts. Sideroblasts are red blood cell precursors and consist of granules with iron-containing proteins called Pappenheimer bodies. These granules are absent when a patient experiences iron deficiency.

Macrocytic anaemia

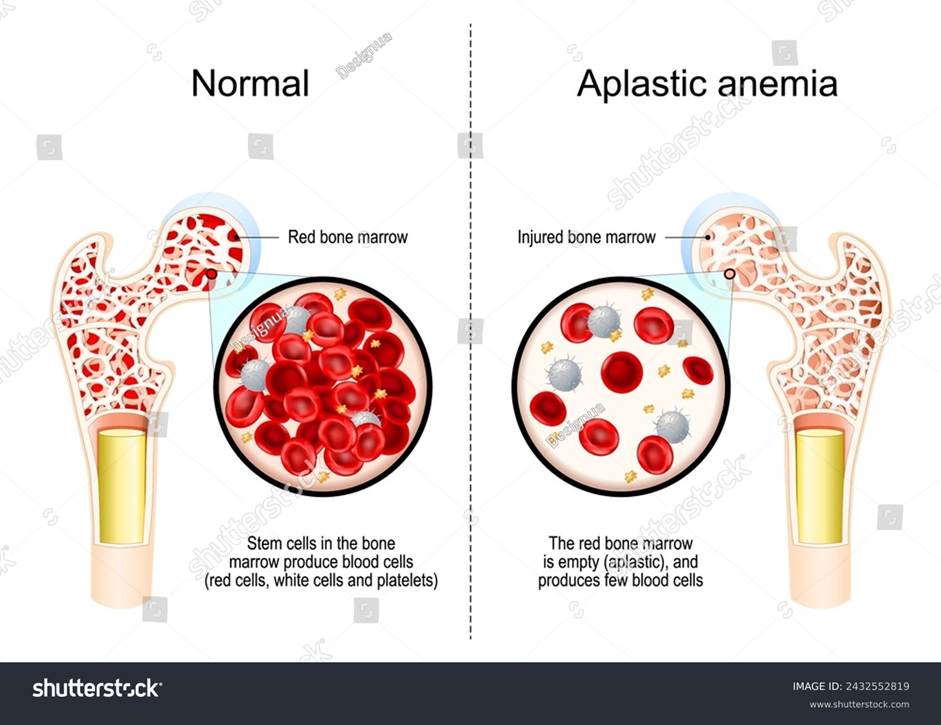

Macrocytic anaemia, as mentioned in Figure 19, arises when there is a high haemoglobin count and red blood cell volume. Amongst the causes of this form of anaemia is aplastic anaemia, where there is low frequency and production of all cells: red, white, and non-cellular fragments of platelets in the blood and bone marrow, as presented in Figure 27. Other potential causes of macrocytic anaemia are combined deficiency of iron and vitamin B12, hypothyroidism, and haemolytic anaemia (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003).

Figure 27: Aplastic anaemia

Polycaethemia

Polycaethemia is the overproduction of red blood cells and hemoglobin. There are two major types: absolute and relative polycaethemia. The absolute type is caused by the elevated synthesis of the hormone erythropoietin, secondary to hypoxia (low oxygen). Some cancers, like the liver, kidneys, and brain (cerebellum) are at risk of polycythemia. When there is a lack of control of stem cells in the bone marrow, this can result in polycythemia vera. Relative polycaethemia is subdivided into dehydration and apparent. Apparent is uncommon and commonly affects middle-aged obese men, and those who have an inadequate consumption of alcohol, and hypertension (high blood pressure) (Ballinger and Pratchett, 2003).

Donating Platelets

Platelets are commonly donated in cases where there is excessive bleeding post-injury and bruising, and abnormal production or excessive destruction of platelets. This is caused by low levels of platelets (thrombocytopenia). Please see Figure 28. One particular type of thrombocytopenia is referred to as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Patients with TTP have a deficiency of a protein, ADAMTS-13. This causes the breakdown of von Willebrand factor, which is essential for the normal function of platelets (Ballinger and Pratchetts, 2003). This can increase the tendency to bleed and result in haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopaenia. Von Willebrand disease is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder where one parent is sufficient to pass it to the progeny.

Donating Plasma

Eligibility To Donate Blood

There are several factors that influence the availability of donors, including psychological factors such as fear of needles and infectious agents. Screening programmes, methods, and eligibility evolved over time. Table 3 summarise key lifestyle, medical and sociodemographic factors that influences the ability to donate (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2025e).

Table 3: Factors that Affect Blood donation

For further information, please visit NHS Blood: https://www.blood.co.uk/who-can-give-blood/can-i-give-blood/

How To Check Your Eligibility Anonymously

Please check your eligibility anonymously via NHS Blood and Transplant:

Did you travel or do you have a particular condition you are unsure about?

Eligibility check to donate blood based on health conditions, medications and travel:

Autologous Blood Transfusion

Autologous blood was mainly performed in the 1980s and 1990s because there was lots of fear of being transmitted with infections during transfusions, namely Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C in the AIDs epidemic (Vanderlinde, Heal and Blumberg, 2002). Hence, there was a time limit of 72 hours to obtain red blood cells intraoperatively (during surgery) and post operatively (after surgery) to maintain adequate levels of haemoglobin (Myers and Collins, 2025). This excludes patients with suspected bacteriaemia (bacteria in the blood).

The type of surgery autologous blood donation is predominantly applied for is elective surgery (Vanderlinde, Heal and Blumberg, 2002). Elective surgeries are non-emergency procedures and are scheduled in advance with thorough care planning.

Throughout the procedure from donating, handling, processing and screening, the risk of infections are minimised in autologous donation and even helps preserve allogenic blood supply. As a result, there are less chances of rejection and alloimmunization (Myers and Collins, 2025). Alloimmunization is defined as when the body produces antibodies against the antigen proteins present on the surface of the cells from the donor.

There are four types of autologous transfusion summarised in Table 4. Preoperative (pre-deposit) autologous donation (PAD), Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution (ANH), Intra-operative and post-operative cell salvage. The most cost-effective is ANH and cell salvage. Some patients require both autologous followed by allogenic, for instance, 20.9% of patients with brain surgeries and 27.3% with heart or vascular surgeries (Sam et al., 2023). Sam et al. (2023) revealed that the levels of haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelets, and International Normalised Ratio (INR) of patients who underwent cardiac surgery were within the normal reference range before and after autologous blood donation. Haematocrit is the packed red blood cell volume of the whole blood. This suggests that autologous is safe and can assist during acute blood loss. Similar results were presented on the 1st and 5th day post-surgery.

Shantikumar et al. (2011) found that patients with ruptured aneurysms who had cell salvage autotransfusion during abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery had fewer allogenic blood transfusions. An aneurysm is an abnormal swelling of the wall of an artery caused by infection or degeneration.

Auditory Learners

Types of Autologous Blood Transfusions: Definition, Types and Advantages By MBBS Naija

Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution By MBBS Naija

Cell Salvage By MedStar Health

Visual and Kinaesthetic Learners

Table 4: Types of Autologous Blood Transfusions

British Guidelines for Intraoperative Cell Salvage

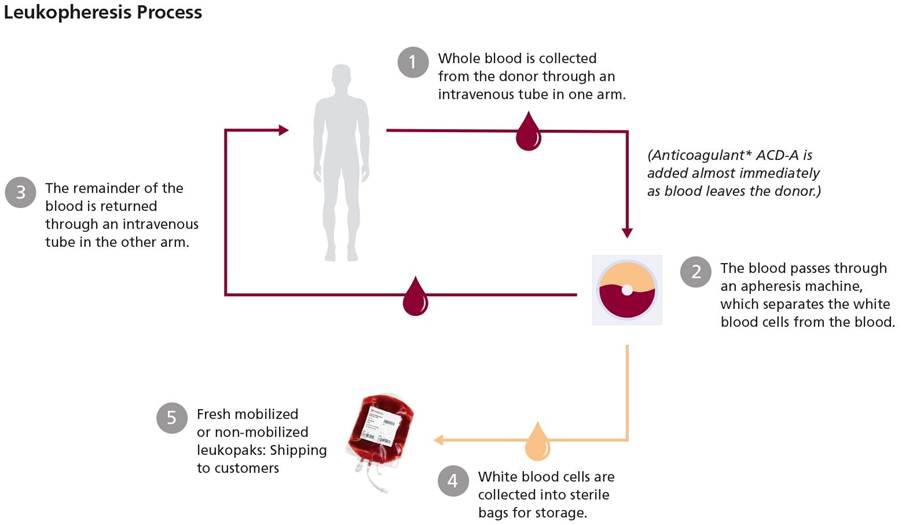

Apheresis

Apheresis is a medical procedure in which specific blood components, such as plasma or platelets, are separated and collected from the whole blood. The other components are then returned to the patient’s circulation (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014). The volume of blood collected should not exceed more than 15% of the total blood volume. In autologous apheresis, which means collecting blood from and returning it to the same person, several methods are described in the earlier sections for obtaining red blood cell concentrates and returning them to the same patient.

In this section, the aim is to review how other blood components are removed by apheresis. For example, if a healthcare professional needs to collect platelets for a patient, the machine separates and collects platelets, while the other components—red blood cells, white blood cells (also called leukocytes), and plasma—are returned to the donor. This collection process is repeated as needed until the required amount or target, called the therapeutic index, is reached. The procedure can require both arms for approximately one hour (Myers and Collins, 2025). Centrifugation, which uses spinning to separate blood components by density, and filtration with different pore sizes, are commonly applied. Intermittent apheresis equipment can use a single vein for both collection and return, while continuous apheresis equipment requires two healthcare professionals known as phlebotomists—one to collect blood and one to return it. The blood components that can be produced via apheresis are summarised in Table 5 (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014).

Table 5: Types of Apheresis

Auditory Learners

Recommended Articles

Alternative Blood Products

Through advancement in research and technology, and the concept of bioethics, a right to what a patient may opt for is paramount. Alternative blood products have been developed, including clotting factor concentrates, erythropoietin, and albumin; some of these are mentioned in Table 6. Other important clotting protein concentrations not mentioned include fibrinogen, fibrin, and antithrombin.

An insight into Haematosis

Many of the clotting factors are produced in the liver, as referenced in Table 6, and are released into the blood to the site of injury (internal or external). The clotting factors are activated in a series of reactions known as the coagulation cascade to form a blood clot (Crampton, 2023). This is a multistep process as presented in Figure 34.

There are three main pathways: intrinsic, extrinsic, and common. The intrinsic pathway, otherwise known as the contact activation pathway. It is stimulated when the blood is in contact with collagen fibres and initiated by a factor present in the damaged blood vessel. The extrinsic pathway, otherwise known as the tissue factor pathway. It is initiated externally to the blood vessel, where a chemical called tissue factor is released by damaged cells. The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways join together to form the common pathway, where a series of chemical reactions form a prothrombin activator. Prothrombin activator activates the prothrombin is activated to thrombin. Thrombin activates soluble protein fibrinogen to fibrin (Crampton, 2023). This is illustrated in Figure 35.

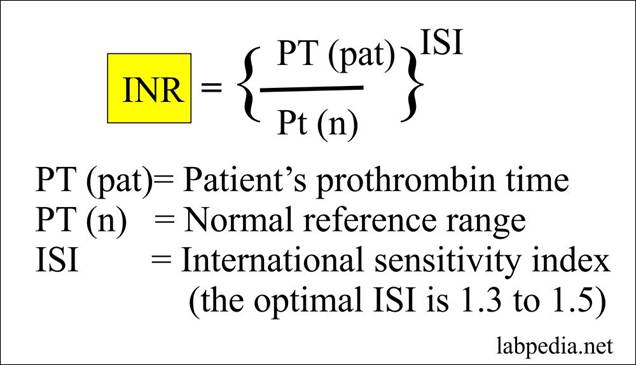

An Insight Into The International Normalized Ratio

The International Normalized Ratio (INR) evaluates the formation of blood clotting via the extrinsic pathway. The INR helps to understand the cause of unexplained bleeding and assess the effectiveness of patients on anticoagulation therapy, e.g., warfarin (Labpedia, 2025). It is applied routinely to monitor health conditions.

The prothrombin time (PT) is expressed as a ratio: the clotting time for the patient’s plasma divided by the time for control plasma. The correction factor, also known as the International Sensitivity Index, is applied to the prothrombin ratio to obtain the ultimate INR. The equation is in Figure 36.

Figure 36: The equation for INR

The INR value of 1 represents normal clotting time. The reference range value is between 0.8 and 1.1. A value of 2 indicates a two-fold increase in the normal clotting time.

The INR in patients who administer anticoagulants orally and in most conditions is 2.0 to 3.0. For instance, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), atrial fibrillation, emboli with atrial fibrillation, and orthopaedic surgery. DVT, also known as phlebothrombosis, is the obstruction of a vein by a blood clot, especially the deep veins of the calf of the leg. Atrial fibrillation is the irregular activity and rhythm of the atria chambers of the heart.

For prophylaxis, the INR is 1.3, whereas if the patient had prosthetic valve prophylaxis, the INR is between 3.0 and 4.0 (Labpedia, 2025). Prophylaxis is a preventative measure against disease. A prosthetic valve is surgically inserted if the patient has leaky or malfunctioning valves. The purpose of the valves is to prevent backflow of blood in the heart chambers.

However, if the patient has pulmonary embolism, it is 2.5 to 3.5. This is the obstruction of the pulmonary artery by a blood clot derived from the leg vein (DVT). The pulmonary artery carries blood that has a low oxygen concentration from the heart to the lungs. Small emboli can damage tissue in the lungs and cause hemoptysis, coughing up blood, whereas large emboli can stimulate acute heart failure or sudden death.

The General Process of Donating Blood

Preparation before consultation

Potential donors need to maintain their health status by regularly eating food containing iron, to rest, avoid alcoholic drinks (for those who drink), and drinking lots of water and non-caffeinated beverages. Examples of food with high iron content are presented in Figure 37.

During Initial Consultation

Donors must positively identify themselves by volunteering their name, date of birth, and permanent address.

Observational health and well-being checks:

- Heart rate/pulse

- Blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Fingerstick haemoglobin test.

A screening questionnaire about their general health, which the donor must sign. A qualified healthcare professional is responsible for countersigning for obtaining the health history. Based on the results, the health care professional can advise whether to donate blood or not, depending on the clinical outcome, with reasoning.

A consent form is also signed where the donor is informed on the procedure, risk, and the opportunity to ask questions. Here, the transactional model of stress and coping is applied at the initial consultation and during the procedure.

Before apheresis can be done, a blood test to examine compatibility of the donor’s red blood cells is required.

- Complete Blood Count

- ABO groups/Rhy typing

- Screening for transmitted disease (viral/bacterial)

- Minor and Major cross-match.

Once cleared through consultation, the collection stage and arrangement takes place.

Collection Of The Donor Blood

Personal details of the potential donor are checked.

The apparatus or equipment for blood collection set must be in date and inspected for any systemic errors or defects according to the standard operating procedures (SOP).

The whole blood, apheresis packs, and sample tubes are labelled in accordance with the SOP.

The most reliable source to obtain haematopoietic stem cells is the cord blood. This is extracted during the delivery of the newborn, processed, and stored (Myers and Collins, 2025). Please see Figure 39.

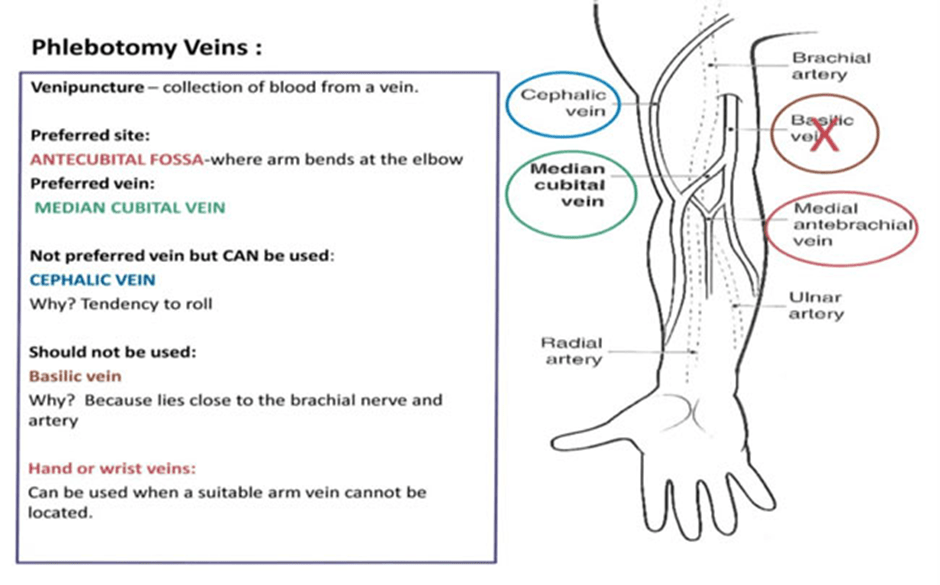

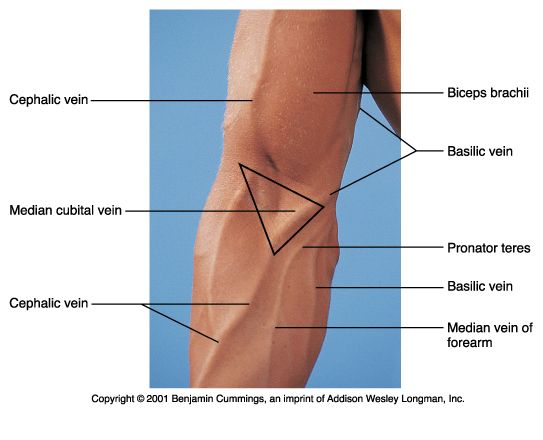

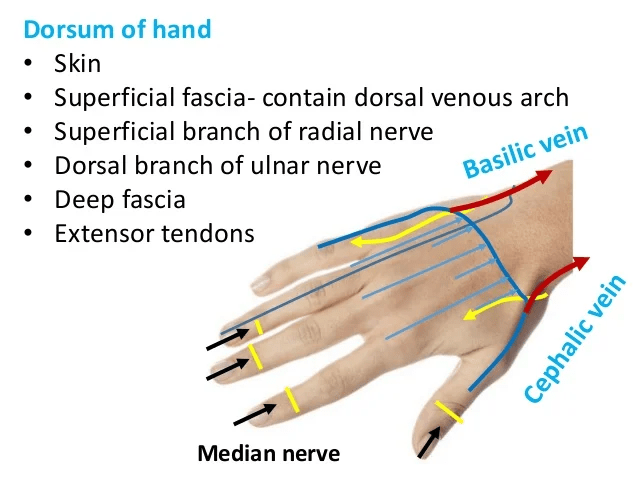

A sterile needle is inserted into the antecubital vein after the site has been hygienically cleansed with 2% chlorohexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol solution. Please see Figures 40, 41, and 42 for schematic diagrams of phlebectomy veins. Alternative sites for venipuncture are the veins on the dorsum of the hand. Please see Figure 43.

The aim is to collect 450 ml of donor blood (Myers and Collins, 2025). Other sources suggest 350 ml or 450 ml is collected. The blood is placed in a donation bag that contains an anti-coagulant, for instance, Citrate Phosphate Dextrose Adenine (CPDA-1). CPDA-1 is predominantly used to preserve whole blood and red blood cells, extending their shelf life up to 35 days (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014).

The bags are made of polyolefin or polyvinyl chloride (PVC). They provide permeability of oxygen and maintain a pH more than 6 for the survival and function of platelets (Simon et al., 2009).

Throughout the blood collection, the donor is monitored on health checks.

What Happens After The Blood Donation Has Been Collected?

The blood samples are kept in a sanitised room and are refrigerated and centrifuged within 5-8 hours to different components. This requires two heavy spins, 5000 g for 10-15 minutes, followed by a light spin, 1500 g for 5-7 minutes. This depends on the centrifuge used. G is the centrifugal force that depends on rotor length and revolutions per minute (rpm) (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014). Storage and transport conditions is per guidelines in an NHS Blood van as presented in Figure 44.

Following blood donation, donors are advised to refrain from heavy lifting, drinking alcohol, and smoking for several hours.

Recommended sources:

Auditory Learners

British Guidelines for Collecting and Processing Blood.

Transactional Model Of Stress And Coping

The transactional model of stress and coping is a cognitive model developed by the eminent psychologist Richard Lazarus. It was published in 1966 in his book ‘Psychological Stress and the Coping Press’ (Ben-Zur, 2019). It was later developed in the 1970s and 1980s alongside Susan Folkman, with further shaping and explaining of the effects on humankind in their book ‘Stress, Appraisal and Coping’ (Ben-Zur, 2019). This psychological model was selected to evaluate its essentiality when organising a discussion with the blood donor and the patient.

There is a significant difference between beliefs and experiences that can shape our perceptions in a positive or negative systemic way with our appraisals, coping responses, and adaptations as presented in Table 7. Our minds are filled with questions as presented in Figure 45. Appraisal is how we evaluate the situation, particularly the idea of donating blood and the aftermath, before expressing feelings and responding to the concept (Frings, 2017).

Donating blood stems from a natural positive belief and sense of duty towards all communities in saving lives, especially in emergency and elective scenarios. The element of trust is significantly important when communicating with potential blood donors who may lack a thorough knowledge or understanding of the concept of blood donations, especially ethnic minority groups residing in Western countries (Thorpe et al., 2023). On the contrary, the levels of stress may rise even with a previous understanding of donating blood as a natural stress response. Therefore, the presence of social support groups of blood donors and enquiries answered by a donor professional can significantly influence the stress and coping response. Close relatives or family members can also facilitate this by attending. The beliefs of people who have not donated blood or choose not to engage in blood donations may change their beliefs.

There is a cultural context that may influence their beliefs and experience when donating blood. For instance, lowering blood pressure, weight loss, and the idea of improving the blood quality by removing unclean blood to stimulate new production of blood cells. This has been discovered in studies from Asia and South America, but it is unknown how proliferative these results are globally (Thorpe et al., 2023). This highlights how characteristics, behaviour, geographical region, products, and age can influence health-related communication and educational strategies (Thorpe et al., 2023).

Moreover, potential blood donors may experience several negative impacts that deter them from donating. Amongst the key reasons is the likelihood of being transmitted with acquired transfusion transmitted infections (TTIs) like Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Other reasons is the negative effect of blood donation on physical appearance, reproductive health, and its impact on the immunity. The idea of having needles and wires can also negatively influence their beliefs (Thorpe et al., 2023). The donor professional is competent in dealing with patients who are feeling nervous and can cover the arm if needles are not wanted to be seen.

Several side effects may arise, including fluctuations in the iron levels and several episodes of headaches. This is why it is essential during the consultation to state the percentage risks of these occurrences because the rarity of such outcomes is small and possible, but not certain. The difference between possibility and certainty can alter one’s perspective.

Therefore, donating blood is transactional; our appraisals drive our response, our responses alter the situation or ourselves, and can influence our appraisals. The response to the reappraisals is to avoid stress and/or alter our coping strategy (Frings, 2017). Jeremy (2025) has provided a plethora of ways for anxiety reduction through restful sleep prior to and after donating blood, consuming iron-containing food for a minimum of two hours to stabilise the sugar level. Drinking water can help the blood donor to remain hydrated and compensate for the blood collected, and ease in finding good veins for venipuncture. Loose sleeves and comfortable clothing can also give ease.

At the climax, the health benefits of donating blood and the compassion of helping others during their tough time are a sign of hope. Listening to music or alternative auditory recordings, for motivational talks or religious speeches (recitation of verses from the holy book. Alternative ideas are reading books and watching videos on people’s own experiences donating blood. Many are posted on the NHS Blood YouTube Channel. Rewarding yourself with something you enjoy (Jeremy, 2025).

Current research aims to understand the link between positive beliefs and evidence in improving blood, for instance, erythropoiesis, and alterations in iron metabolism after donating blood (Thorpe et al., 2023).

Table 7: The stages involved in the Transaction model for stress and coping

Risks to Blood Transfusion

Patient donors, when opting to do allogenic or autologous blood transfusions, must be monitored for adverse events. Certified medical personnel undergo training on how to screen potential blood donors, utilise sterile equipment, collect blood, and oversee the blood donation process. Risks and benefits must be considered for the individual patient, the blood donor, and the healthcare professional. It is vital for blood donors and patients to rest during and after donating blood. Around the time of donation, acute reactions may occur, for instance, injuries, swelling, and fainting, whereas, in the longer term, there is a potential risk of iron deficiency. Nevertheless, donating blood is a safe procedure, and it is rare that such symptoms may arise (Thorpe et al., 2022).

Screening tests have helped abridge the risk of infection from allogenic transfusions, for instance, HIV, and human T-cell lymphotropic viruses (HTLV). However, there is a potential risk for TTI, alloimmunization, and metabolic imbalances. This can influence the psychological and economic statuses of patients and their families.

Following health checks, a potential donor or autologous patient may be asked to defer donations with a reason. The aim is to be clear and calm in the approach when explaining to the patient (McSporran et al., 2024).

In cases where the patient has the all clear to proceed with donating or receiving blood. Appropriate counselling should be available if needed when faced with anxiety (McSporran et al., 2024).

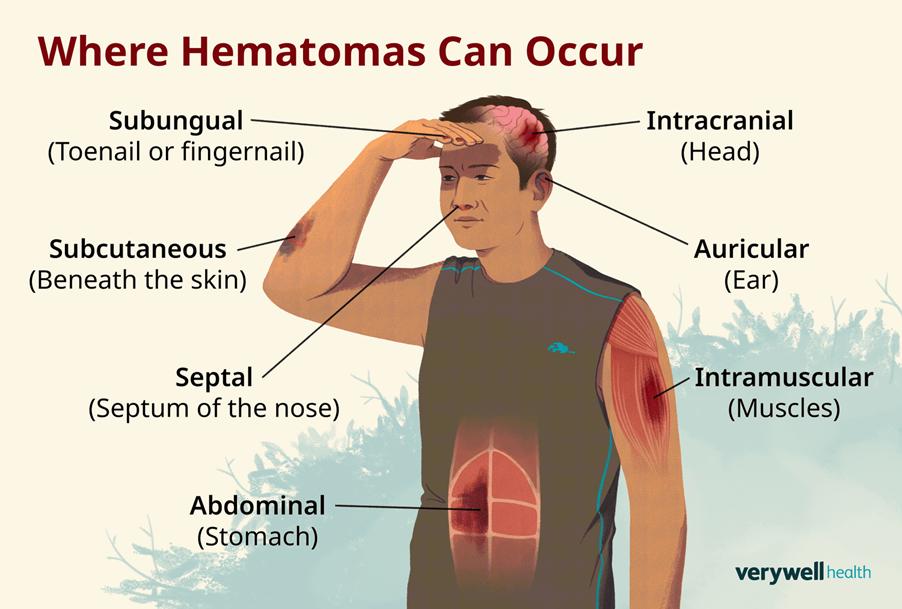

The most frequent blood complication is traumatic haematoma when the needle is removed. A haematoma is defined as the accumulation of blood in the tissues that clots, forming swelling. It is vital to apply pressure and use ice to compress the affected area upon needle removal to prevent the formation of a haematoma intramuscularly. Please see Figure 46. Haematomas that arise from blood donations are typically small, with rare chances of affecting other tissues that are in close proximity. Other forms of haematoma arise when there is an injury, raising pressure in the skull, with a potential tear of the blood vessel, and require surgical treatment.

The second most common complication that manifests following blood donation is fainting (syncope). Please see Figure 47. This is where there is a loss of consciousness and low blood pressure, obstructing the blood flow in the brain. This is called vasovagal syncope and may be linked to hypovolaemia. Other symptoms may arise like dizziness, pale colouration, sweating, and weakness. This may likely occur during their first donation of blood or when experiencing emotional shock, injury, perfused bleeding, or standing for prolonged periods. If vasovagal syncope occurs during blood donation, the process is paused, and the appropriate patient care is then provided. Alternatively, if the syncope occurred after donating blood, the appropriate emergency guidelines are followed, where the patient is placed in a reclined position. Once well, they can consume healthy food and beverages to regain their energy and overall health. Additional symptoms that may arise during blood donation are nausea (feeling sick) and vomiting.

Fainting may also arise during apheresis. In general, autologous blood transfusion alleviates blood shortages and saves blood (Sam et al., 2023). Alternatively, there may be a risk of anaemia and loss of donated units, which may cause delay. This is why donors are tested for cytopenia; loss of mature blood cells. Loss of blood incidental to procedure should not exceed 25 ml weekly (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014). This is overcome by using allogenic transfusion. Perioral paresthesia may also arise during autologous blood donations and include tingling, numbness around the mouth, headache, and dyspnoea.

Furthermore, some patients may experience a range from mild allergic reactions to fatal reactions as a result of blood components of a blood donor. This is caused by white blood cells, plasma proteins, red blood cells, and pathogens. This is why modifications to blood production take place, for instance, leukocyte reduction, irradiation, and pathogen reduction or inactivation.

Leukocyte reduction

To succeed in leukoreduction, the buffy coat is removed, where most leukocytes are found. Packed red blood cells (PRBC) and preparing platelet concentrates (PLTC) are alternatives with fewer leukocytes <1·2 × 10^9. It helps remove microaggregate formation and lower febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions (FNHTR). FNHTR is the most common type of transfusion reaction, characterized by fever and chills occurring during or shortly after a blood transfusion (within four hours of blood transfusion). This is typically caused by cytokine release from donor leukocytes. The fever is at least 1 degree Celsius above, reaching 38 degrees Celsius. Other symptoms are tachypnoea, headache, and vomiting (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014).

Irradiation

Granulocytes, a type of white blood cell, in which basophils and eosinophils are involved in allergic responses, are irradiated between 25 and 50 Gray (Gy). Leukocytes can also be exposed to ultraviolet light via a process called photopheresis. This involves patients being administered with a photoactive dye called psoralen (8-methoxypsoralen or 8 MOP orally. Apheresis is then performed a few hours later and exposed to UV. This is commonly performed in patients with T cell lymphoma (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014).

Pathogen reduction

The aim is to eliminate potential pathogens from donated blood and minimise transfusion-associated infections by testing for these specific pathogens and targeting their DNA, but this has not been applied universally in health institutions. Filters with a pore size of 0.22 nm have been applied to remove viruses with a protein membrane and not a lipid envelope. Additional trials aim to assess its efficacy and safety (Basu and Kulkarni, 2014). In cases of COVID-19, transplantation and elective surgeries were delayed, and restricted transfusion, particularly frozen fresh plasma (FFP) and plateletpheresis. In contrast, there is solid evidence that suggests there is no link between COVID-19 and donating blood because plasma and platelet products collected during the pandemic have not shown any harm, despite COVID antibodies were conveyed by transfusion (Basu and Kulkarni, 2024).

In vector-borne diseases such as malaria, caused by Plasmodium Flacipurum and can be transmitted by mosquitoes. Researchers advised patients with a history of malaria to defer from donating blood for three years. Residents who reside in a region where the risk of malaria is high are ineligible to donate for three to four years. However, if the malaria serology test is negative, this indicates they cannot donate blood for 3 to 4 months, whereas a positive test is a full prohibition from donating blood in the UK.

The addition of Psaralen with UV light seem to be effective when removing pathogens in platelets and plasma. Other trials have developed S303, Helinx in red blood cells, where experimental results were successful (Basu and Kulkarni, 2024).

Latest Research Updates On Blood

Japanese researchers at Nara University have developed a purple artificial blood product that has surpassed first-generation chemically modified haemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOC). HBOCs are known for their elevated risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) and mortality in clinical trials (Azuma et al., 2022). Upon investigating the cause, it was found to be associated with their high affinity for toxic gases like nitric oxide, their acellular structure, and small molecular size. This led to symptomatic effects like high blood pressure, vasoconstriction, and oxidative lesions (Azuma et al., 2022).

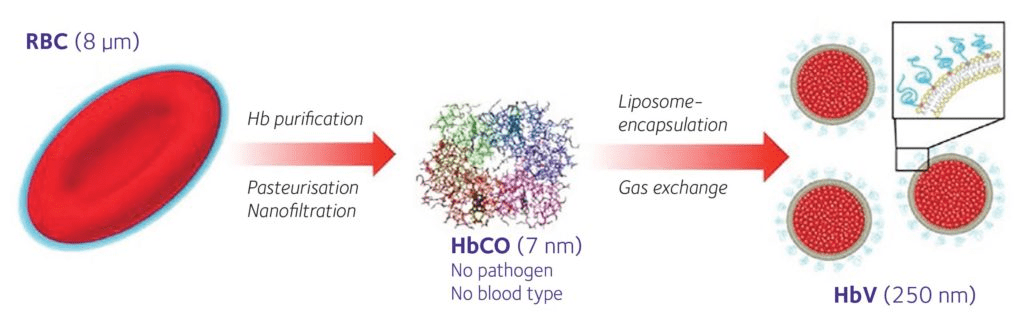

The artificial blood product is a haemoglobin vesicle (HbV) encapsulated in a PEGylated phospholipid. Please see Figure 48. It has a mean particle diameter of 225- 285 nm and mimics the function of natural red blood cells. It has high efficacy and longer therapeutic time when higher dosage is used. This enables HbV to carry oxygen for several hours in patients with haemorrhagic shock until a transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBC) arrives.

HbV is composed of expired donor blood; all blood type antigens are removed, making it universally compatible. In other words, there is no A, B, AB, no O blood type. In addition, there is an absence of viruses, which lowers the likelihood of viral-transmitted infections, particularly HIV, HTLV, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). HbV can be applied in emergency care in war zones, where many lives are saved. It is also useful in rural areas that lack health facilities, mobile clinics, ambulances, and in natural disasters (Bhaskaran, 2025). If the location lacks cold storage or is unreliable, this artificial product can cope up to two years in room temperature conditions and five years with light refrigeration (Azuma et al., 2022).

In 2022, Japanese researchers conducted a clinical trial. Twelve healthy male volunteer subjects aged between 20 and 50 years old, weighing 50 to 85 kg, and body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 25.00 kg/m2. They were administered with single doses of HbV that were suspended in saline. The haemoglobin level is between 8.5 to 11.6 g/dL. There were three cohorts, each with the same number of participants: four. However, each cohort varied in the dose of HbV suspension, whether premedication was given, and the rate in which HbV suspension was performed.

Subjects in Cohort 1 had 10 mL of HbV suspension with no premedication. It was administered at a rate of 1 mL/min. In the first week, week 1, HbV suspension was given to one participant, and in the subsequent week, week 2, three participants were given HbV suspension.

Subjects in Cohort 2 were administered 50 mL of HbV suspension and no premedication. Similar to Cohort 1, the HbV suspension was administered to one subject in Week 1 and three in Week 2. However, the flow rate varied for Cohort 1; subjects in Cohort 2 initially received 1 mL/min for 10 minutes, followed by 2.5 mL/min.

In Cohort 3, a single dose of 100 mL of HbV suspension was administered to one subject per week at a rate of 1 mL/min for 10 minutes, followed by 2.5 mL/min. The premedications were taken one hour before infusion of HbV: steroids 6.6 mg dexamethasone intravenously. Both 20 mg famotidine and 500 mg acetaminophen were taken orally, per os (PO).

After completing the HbV suspension, the twelve subjects stayed at home for four days and were monitored on Days 5, 8, and 15 (Azuma et al. 2022). Their systolic blood pressure showed minimal to no change before and after HbV suspension (Azuma et al., 2022).

Monitoring their health checks, there were no changes made before and after with their systolic blood pressure (Azuma et al., 2022). However, there was a variation in temperature. In Cohort 1, two subjects recorded temperatures between 37 and 38 degrees Celsius. In Cohort 2, one subject had a similar temperature range. Only one subject in each of Cohorts 1 and 2 had a temperature above 38 degrees Celsius.

The majority of the subjects did not have conjunctivitis, with the exception of one in Cohort 2. Conjunctivitis is the inflammation of the delicate mucous membrane that covers the front of the eyes and part of the eyelid. It is caused by physical or chemical irritation and viral or bacterial infections. As a result, eye discomfort, swelling, redness, and the formation of pus discharge occur.

The following health observations were checked for Cohort 3: oxygen levels, electrocardiogram, clinical chemistry, haematology, urine analysis before and after administration. The role of the complement system (C3, C4, 50% hemolytic complement activity; CH50), C-reactive protein, and anti-PEG antibody was added to laboratory tests as indicators for inflammation and how the immune response is orchestrated.

Some of the laboratory values were outside the normal range, for example. There was a high concentration of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) in subjects in Cohort 1 on Day 2, with a concentration of 151 U/L. The normal reference range is between 81.3 and 145.5 U/L. Another example is Albumin, on Day 8 and 15, there was an elevation where it was 3.8 g/dl and 4.2 g/dl in Cohort 2. It still remained high on Day 18 with a plasma concentration of 4.6 g/dL.

Liver enzymes, ALT and AST, were high on Day 8 in Cohort 3 but returned to normal on Day 15. The total cholesterol levels declined on Day 8 and 15; 116 mg/dL and 112 mg/dL, respectively. The normal reference ranges are between 120.7 and 210.8 mg/dL. This returned back to normal level on Day 24 in Cohort 2 without clinical signs and symptoms.

In Cohort 3, there was a slight increase in C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker, in three participants. The highest peak was 0.99 mg/dL on Day 2. However, none of the subjects had the high temperature aforementioned earlier, indicating fever.

The presence of fever in some patients in Cohorts 1 and 2 could indicate that interleukin-6 (IL-6) was produced. No significant decrease in CH50, C3, or C4 of the complement system was found in any subject in Cohort 3, except for one who had a small deduction on Day 1 (Azuma et al. 2022).

Furthermore, none of the patients had serious adverse effects (SAE). In Cohort 1, 75% of patients (n=3) had an infusion reaction. All three had a burning sensation. Only one had flushing, head dullness, fatigue, dizziness, and a feeling of strangulation.

On the other hand, Cohort 2 had no infusion reaction. Subjects in Cohort 3 had alternate infuse reactions. There was a sense of discomfort in the lower back (n=1), rash, and wheal (n=1). However, this does not undermine the importance and efficiency of their role in the field of haematology.

The research team now aims to upscale the research study by increasing the dose to 400 mL and involving more participants on a larger scale. If successful, the objective is to initiate clinical use by 2030 (Bhaskaran, 2025). On the contrary, the research team had several obstacles, for instance, gaining approval from global regulatory agencies and meeting large-scale demand could cause delay and critical evaluation (Azuma et al. 2022). Thus, these limitations need to be overcome before it can be used in clinical settings.

Moreover, other researchers have investigated other methods to encapsulate haemoglobin. Chang (2017) revealed how covering the haemoglobin protein molecule with two enzymes: carbonic anhydrase and superoxide dismutase/catalase can maximise the transportation of carbon dioxide and free radical scavenging (Chang, 2017). This presents another way in which erythrocytes are mimicked physiologically. In addition, a dried bio-inspired red blood cell substitute, Erythromer, is critically useful when there is minimal transfusion in emergency settings (KaloCyte, 2025). It sequesters nitric oxide, prevent methaemoglobin accumulation, which are needed to maintain haemoglobin oxygen carrying capacity (Pan et al., 2016).

Furthermore, researchers have developed artificial platelets by modifying their surface area so signalling molecules or ligands can be added (Hagisawa et al., 2021). The H12-ADP liposomes can interact with activated platelets via the glycoprotein H12 and IIb/IIIa. This increases aggregation of activated platelets by releasing adenosine diphosphate (ADP) from the liposomes. The H12-ADP liposomes remain in the blood circulation for 24 hours after injection if they do not interact with activated platelets at the injury site. ADP is metabolised to allantoin and excreted in the urine within 6 hours. They can be refrigerated for 6 hours without shaking at 4˚C. This is a shorter period than the storage of PTLC (platelet concentrates) which must be utilized within 4 days and constant shaking movements at 22˚C (Hagisawa et al. 2021).

Conclusion

Ultimately, the opportunity to donate one’s blood is a step into a transforming lifesaving venture that is worthy of emulation today and for generations to come. YOUR blood can be the reason someone you know or do not know; breaths longer, hugs tighter and smiles wider. With a constant need to get blood, there is an instant happiness in giving it, whether through allogenic or autologous and apheresis mechanisms.

Therapeutic interventions to treat coagulopathies and blood disorders and facilitate acute blood loss during elective and emergency surgeries are dependent on time and demand of specific blood types to prevent reactions orchestrated by the immune system. Methods to prevent adverse effects can be applied through leukodepletion, leukoreduction, irradiation, and cryopreservation. This ensures the most relevant blood component required for the patient’s health status is applied, and the remainder is returned to the body. The novel introduction of artificial blood products by Japanese researchers is a step forward to ensure blood is universally applicable for all patients without worrying about compatibility testing and agglutination. This, in turn, can help save lives and efficiency in time. The transactional model of stress and coping illustrates the appraisals, responses, and perceptions that patients and blood donors may feel during the process. The ability to overcome negative beliefs and experiences is through strategic ideas to relax the mindset, speaking to the donor professional, relatives, and social support groups. Remember the outcome of saving lives and supporting all communities.

Further Information

NHS Blood and Transplant https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/

NHS Blood Donation https://www.blood.co.uk/

Blood Cancer Alliance https://www.bloodcanceralliance.org/

References

AG. (2014) Giant Langhans Cell and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.medical-labs.net/giant-langhans-cell-and-mycobacterium-tuberculosis-2459/ (Accessed: 13th August 2025)

Azuma, H., Amano, T., Kamiyama, N., Takehara, N., Maki Jingu, Takagi, H., Sugita, O., Kobayashi, N., Kure, T., Shimizu, T., Ishida, T., Matsumoto, M. and Sakai, H. (2022). First-in-human phase 1 trial of hemoglobin vesicles as artificial red blood cells developed for use as a transfusion alternative. Blood Advances, [online] 6(21), pp.5711–5715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007977.

Ballinger, A. and Patchett, S. (2003) Saunder’s Pocket Essentials of Clinical Medicine. London: Elsevier.

Basu, D. and Kulkarni, R. (2014). Overview of blood components and their preparation. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 58(5), p.529. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.144647.

Ben-Zur, H. (2019). Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2128-1

Bhaskaran, H. (2025) Purple Lifeline: Japan’s Universal Artificial Blood Breakthrough. Available at: https://www.medboundtimes.com/biotechnology/japan-universal-blood-artificial-breakthrough (Accessed: 18th August 2025)

Biology Insights (2025) Human Red Blood Cell: Function, Lifespan, & Common Conditions. Available at: https://biologyinsights.com/human-red-blood-cell-function-lifespan-common-conditions/ (Accessed: 9th August 2025)

Carroll, C. and Young, F. (2021). Intraoperative Cell Salvage. BJA Education, [online] 21(3), pp.95–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.11.007.

Chang, T.M. (2017). Translational feasibility of soluble nanobiotherapeutics with enhanced red blood cell functions. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 45(4), pp. 671-676. https://doi.org/10.1 080/21691401.2017.1293676.

Ciurea, S.O., de Lima, M., Cano, P., Korbling, M., Giralt, S., Shpall, E.J., Wang, X., Thall, P.F., Champlin, R.E. and Fernandez-Vina, M. (2009). High Risk of Graft Failure in Patients With Anti-HLA Antibodies Undergoing Haploidentical Stem-Cell Transplantation. Transplantation, 88(8), pp.1019–1024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0b013e3181b9d710.

Clemons, E. (2024) Your Red Blood Cells (RBCs). Available at: https://livebloodonline.com/your-red-blood-cells-rbcs/#:~:text=RBCs%20are%20formed%20in%20the%20red%20bone%20marrow,million%20old%20RBCs%20are%20broken%20down%20per%20second (Accessed: 9th August 2025)

County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust (n.d) Give the gift of life Available at: https://www.cddft.nhs.uk/patients-and-visitors/your-care-hospital/accessibility-reasonable-adjustments/organ-donation(Accessed: 19th August 2025)

Crampton, L. (2023) How Blood Clots: Platelets and the Coagulation Cascade. Available at: https://owlcation.com/stem/how-does-blood-clot-and-what-causes-coagulation (Accessed: 19th August 2025)

Dean, L. (2005) Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2263/ (Accessed: 19th August 2025)

DKMS Foundation (2018) Difference between organ, blood and stem cell donation. Available at: https://www.dkms.org.uk/get-involved/stories/difference-between-organ-blood-and-stem-cell-donation (Accessed: 8th August 2025)

Focosi, D., Zucca, A. and Scatena, F. (2011). The Role of Anti-HLA Antibodies in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 17(11), pp.1585–1588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.06.004.

Frings, D. (2017) The transactional model of stress and coping. Available at: https://psychologyitbetter.com/transactional-model-stress-coping (Accessed: 18th August 2025)

Giri, D. (2019) Cross Matching: Types, Principle, Procedure and Interpretation. Available at: https://laboratorytests.org/cross-matching/ (Accessed: 12th August 2025)

Hagisawa, K., Kinoshita, M., Sakai, H. and Takeoka, S. (2021) Artificial Blood Transfusion: A new chapter in an old story. Physiology News Magazine, 121. Available at: https://www.physoc.org/magazine-articles/artificial-blood-transfusion/ (Accessed: 19th August 2025)

Heath, M. and Shander, A. (2025) Surgical blood conservation: Intraoperative blood salvage. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/surgical-blood-conservation-intraoperative-blood-salvage (Accessed: 16th August 2025.

Hebert, P.C., Wells, G., Blajchman, M.A., Marshall, J., Martin, C., Pagliarello, G., Tweeddale, M., Schweitzer, I. and Yetisir, E. (1999). A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial of Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care. New England Journal Of Medicine, 162(1), pp.280–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-199907000-00110.

Jeremy, T. (2024) How to Overcome Your Fear of Donating Blood Available at: https://www.vitalant.org/blog/blood-donation-basics/how-to-overcome-your-fear-of-donating-blood (Accessed: 18th August 2025)

Kalocyte (2025) Discover ErythroMer. Available at: https://kalocyte.com/ (Accessed: 19th August 2025)

Knudsen, K. (2025) Blood Components. Available at: https://anesthguide.com/topic/blood-components/ (Accessed: 17th August 2025)

Labpedia (2025) Coagulation:- part 5 – INR (International Normalized Ratio), PT and PTT. Available at: https://labpedia.net/coagulation-part-5-inr-international-normalized-ratio-pt-ptt/ (Accessed: 17th August 2025)

Lee, R.I. (1917). A Simple And Rapid Method For The Selection Of Suitable Donors For Transfusion By The Determination Of Blood Groups. BMJ, 2(2969), pp.684–685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2969.684.

Lewisohn, R. (1958). The Citrate Method of Blood Transfusion in Retrospect. Acta Haematologica, 20(1-4), pp.215–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000205485.

Makowicz, D., Dziubaszewska, R., Lisowicz, K. and Makowicz, N. (2022). Impact of regular blood donation on the human body; donors’ perspective. Donors’ opinion on side effects of regular blood donation on human body. Journal of Transfusion Medicine, 15(2), pp.133–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.5603/jtm.2022.0011.

McSporran, W., Anand, R., Bolton-Maggs, P., Madgwick, K., McLintock, L. and Nwankiti, K. (2024). Guideline on the use of predeposit autologous donation prepared by the BSH Blood Transfusion Task Force. British Journal of Haematology, 204, pp. 2210-2216 doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.19374.

Medtronic (2020)Cardiotomy Reservoirs. Available at: https://europe.medtronic.com/xd-en/healthcare-professionals/products/cardiovascular/cardiopulmonary/intersept-cardiotomy-reservoirs.html (Accessed: 16th August 2025)