It is well-established that the risk factors for bowel cancer are augmented with lifestyle factors and sedentary behaviour linked to obesity, a high-fat diet, alcohol, tobacco, and poor exercise levels. The aim of this article is to divert your attention to new risks of bowel cancer recently discovered: pathogenic bacteria, overuse of antibiotics and cystic fibrosis.

New risk factor one: Pathogenic bacteria can cause bowel cancer

Some pathogenic forms of bacteria in the gut microbiota increase the risk of gastroenteritis (inflammation of the bowel), acute diarrhoea infections and bowel cancer. It is characterised by vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain and use of antibiotics was seen to increase colonization by pathogenic bacteria (Sun, 2022).

Example One: Pathogenic E. coli

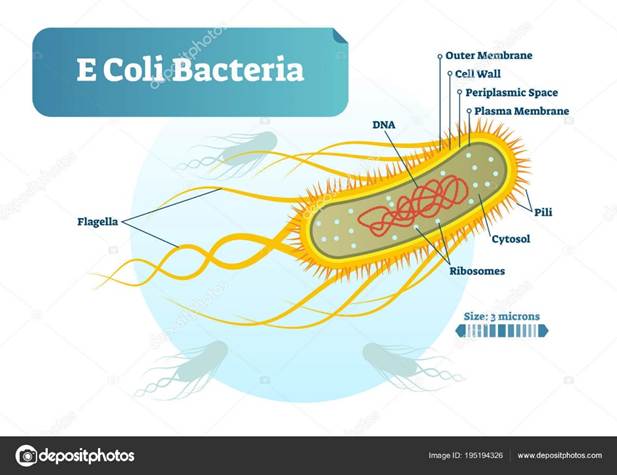

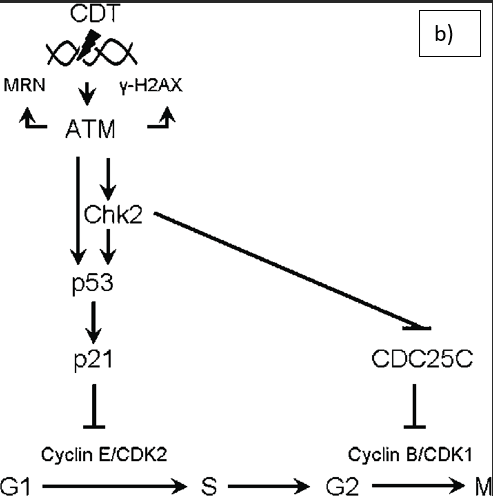

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a type of bacteria that is universal and found in the gut microbiota. They are invisible to the naked eye, and a device called a microscope is used to visualize them. There are five strains: A, B1, B2, D, and E. Some bacteria are good and found in the gut microbiota. They are referred to as Commensal bacteria.

However, pathogenic strains of B2 and Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) can produce cytolethal distending toxins (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023; Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, and Luria-Pérez, 2019). The structure of the E. coli bacteria is illustrated in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1: Structure of the E. coli bacteria

Figure 2: Microscopic image of E.coli X40,000. (Creative Commons, 2025)

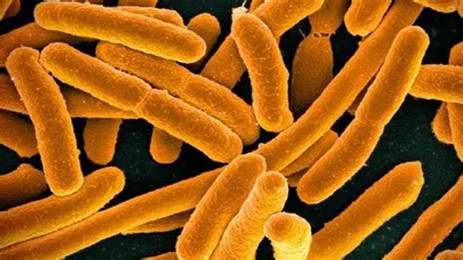

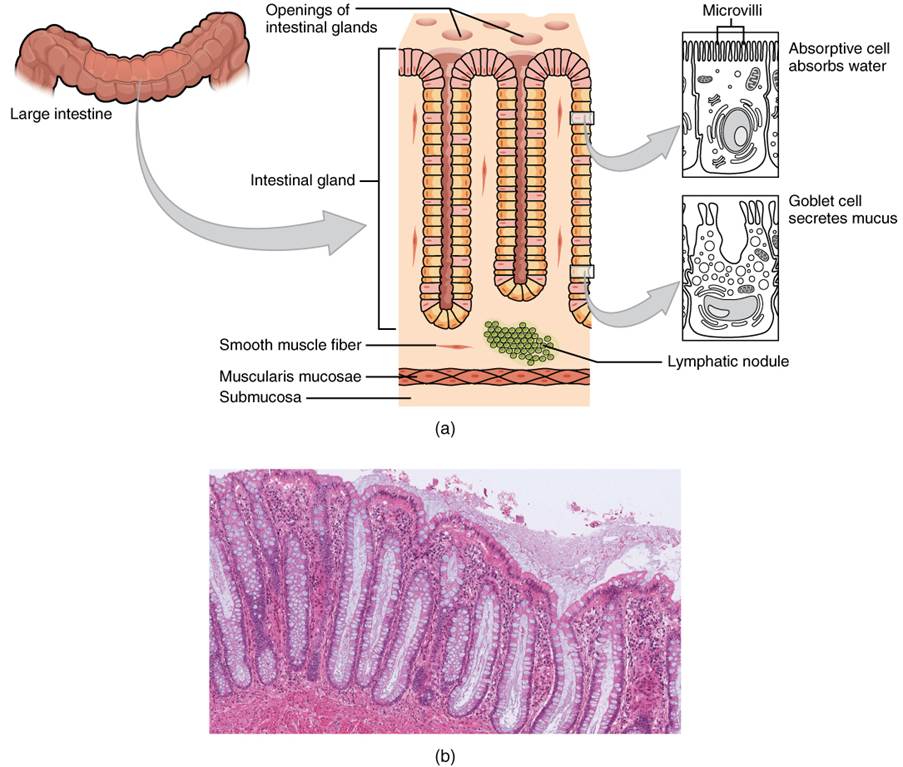

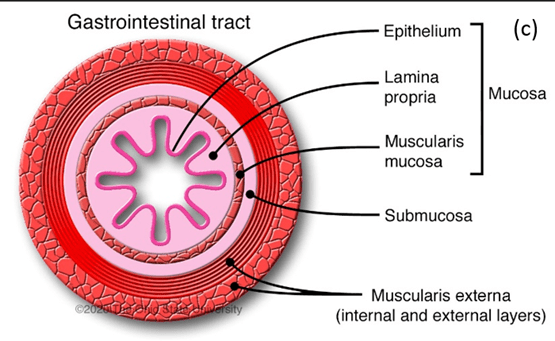

Several studies found that Escherichia coli (E. coli) colonization has been found in the mucosal lining of the colon more than healthy patients – please see the structure of the large intestine in Figure 2 and 3 (Yusuf, Sampath and Umar, 2023). The layers of the large intestine around the lumen. It is made of two layers: inner and outer layer. The inner layer consists of mucosa and submucosa. It is surrounded by the outer layer called the serosa.

Figure 3: Cross-section of the large intestine. (Creative Commons, 2025).

How does pathogenic E. coli cause infection and bowel cancer?

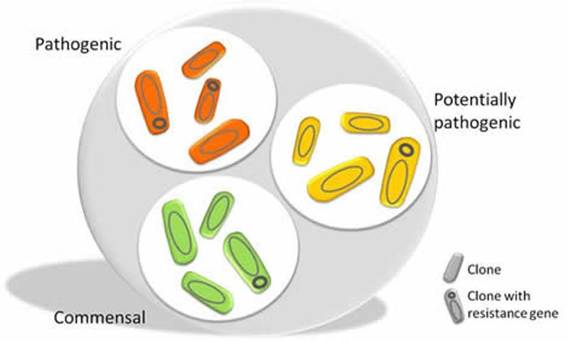

E. coli has a sugar capsule (polysaccharide) that releases toxins causing DNA damage and negatively affecting differentiation of cells, proliferation, and apoptosis. They can evade the immune response and minimize the host complement system (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019; Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al., 2020; Wassenaar, 2018; Costa et al., 2015). Figure 4 illustrates how some E. coli strains can be commensal, potentially pathogenic, or exhibit fully pathogenic properties. The presence of the resistance gene can halt the effect of antibiotics by allowing the pathogenic strain to multiply and colonize the target site.

Figure 4: Different strains of the E. coli (Creative Commons, 2025)

Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli

The first pathogenic strain of E. coli was Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC). Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, and Luria-Pérez (2019) discovered that AIEC cellular adhesion receptor can increase its infection potential in the epithelia of the intestines. It is associated with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEACAM6), interleukin- (IL-6), and the virulence factor colibactin.

Colibactin is a type of secondary metabolite produced by non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)–polyketide synthase (PKS) (NRPS-PKS) (Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al., 2021). It acts as a DNA alkylating agent that induces DNA mutations on adenine residues. The formation of double-stranded breaks (DSB) promotes DNA damage response and tumour progression (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019; Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al., 2021; El-Aouar Filho et al., 2017). In vitro studies in cell lines infected with E. coli pks + strains presented a high level of cell cycle arrest and an abnormal number of chromosomes (aneuploidy). For instance, there were cases where cells had four sets of chromosomes instead of two (tetraploidy). The expression of the protein SUMO-specific protease 1 (SENP-1) is prevented by miR-20a-5P. miR-20a-5P is a non-coding single-stranded RNA molecule. This stimulates cellular senescence and develops colon cancer (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019; Wassenaar, 2018).

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

Another pathogenic strain of E. coli linked with several molecular mechanisms in colon cancer is Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019). Through a GTPase Rho A-dependent pathway, EPEC can activate the cytokine, macrophage-inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1). This elevates the growth and survival of cancer cells. The survival phenotype of colon cancer cells is also stimulated by the autophosphorylation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and proinflammatory mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathways (Chen et al., 2016). The effector protein, EspF enters the epithelial cells in the lining of the colon via the E. coli type III secretion system (T3SS) and also decreases levels of DNA repair proteins mismatch repair (MMR) and rupture tight junction proteins. The proteins, occludin and claudin on the intestinal epithelium stimulate carcinogenesis and metastasis (Elliott et al., 2000; Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019). This secretory system is encoded by the Locus of Enterocyte Effacement (LEE) to deliver virulence effectors to infected host cells (El-Aouar et al., 2017). The secretory system is also applied by another E. coli strain Enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain (EHEC) (Hsu et al., 2008). Both EHEC and EPEC are causative factors for infections experienced by children (El-Aouar et al., 2017).

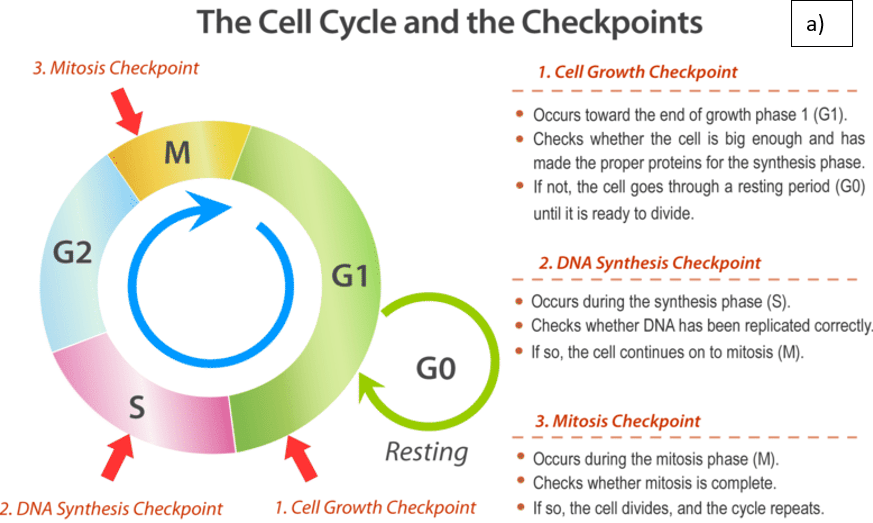

Moreover, other proteins are synthesized by pathogenic E. coli strains. This can be divided into cytolethal-distending toxin (CDT) and cyclomodulins. CDT can dysregulate the cell cycle and stimulate the malignant transformation of epithelial cells by altering cytokine synthesis and promoting local inflammation at the colonic site. CDT-induced cell cycle arrest can occur in the G1 and G2 phases where growth commonly occurs – please see Figure 5. In the G1 phase, CDT activates the mutated tumour suppressor protein, p53, and p21Cip1. This causes the deactivation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) and cyclin E, which regulate the G1-S phase in the cell cycle. The inhibition of CDK-cyclin complexes blocks cell cycle progression. Other cyclins are also downregulated, for instance, cyclin D1.

Further DNA damage and cell cycle arrest in the G2 phase is stimulated by the ATM kinase and inhibiting the association of chk2-mediated inactivation of cell division cycle 25 (Cdc25c) C phosphatase with CDK1 by sequestering Cdc25c via checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2). The translation step in protein synthesis is prevented by cleaving the chaperone BiP by the enzyme Subtilase AB. Subtilase AB toxin binds to integrin at the cell surface. Collectively, these genotoxic effects and ATM-mediated DNA damage stimulated genomic instability, cellular senescence, and intrinsic apoptotic pathway where pro-apoptotic proteins Bax, Bcl-2, cytochrome C, increasing the caspase cascade (Graillot et al., 2016).

Figure 5: The effect of CDT on the cell cycle. A) The normal cell cycle B) CDT-induced DNA damage. CDT stimulates DNA double-strand breaks, the DNA damage response is mediated by the ATM kinase and activates the the multifunctional protein complex. The protein complex consists of Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 (MRN), histone H2AX, the cell cycle regulator checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) and the transcription factor p53. Inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase-cyclin complexes blocks cell cycle progression by the p53-induced activation of p21 and Chk2mediated inactivation of cell division cycle 25 (CDC25) C phosphatase (Creative Commons, 2025; Jinadasa et al., 2011).

Cyclomodulins are a family of bacterial toxins and effector proteins that can induce a functional class of virulence factors that negatively affect the cell cycle and carcinogenesis (Graillot et al., 2016; Nougayrède et al., 2005). A key example is colibactin synthesized by E. coli and functions as a cyclomodulin and CDT genotoxin. Other examples of cyclomodulins are Cycle inhibiting factor (Cif) and Cytotoxic Necrotizing Factor 1 (CNF1). Cif are effector proteins secreted by the T3SS in EHEC and EPEC strains. On the other hand, CIF is not coded by LEE but rather a lambda bacteriophage via horizontal transfer. Lambdoid prophage cannot insert its DNA through a bacterial cell membrane. It has a J protein in the tip of its tail that interacts with the maltose outer membrane porins in the membrane of the host E. coli. This integrates DNA into the nucleus where it temporally controls transcription patterns and expression of target genes (Casjens and Hendrix, 2016).

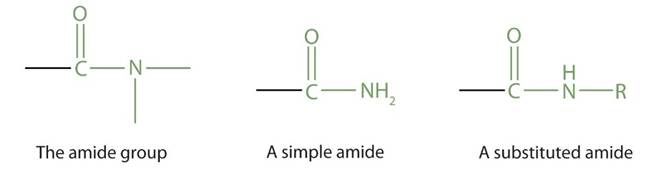

Cif stimulates nuclear DNA elongation on cells and promotes the division of infected slow-growing E. coli cells (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019). Similar to CDT, CIF can induce cell cycle arrest at G1/2 and G2/M points by deamidation of the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8. Deamidation is a type of chemical reaction where the removal of the amide functional group present in the side chain of the amino acid structure for glutamine or asparagine changes to another functional group. The amide functional group consists of a nitrogen atom (-N) bound to a carbonyl carbon atom (C=O). Please see Figure 6. A simple Amide is where two remaining bonds of nitrogen are linked with hydrogen atoms. A substituted amide is where two remaining bonds of nitrogen are associated with alkyl (removal of a hydrogen atom) or aryl group (LibreTexts, n.d.).

The deamidation of NEDD8 influences the NEDD8-Cullin linkage. This causes the enzyme Cullin-Ring ubiquitin Ligase (CRL) to be deactivated. It can affect the ubiquitin-dependent degradation pathway. The CRL substrates increase their concentration and the CDK inhibitors cause cell cycle arrest (El-Aouar Filho et al., 2017). This demonstrates how the virulence factor, Cif halts the cell cycle and increases the rate of carcinogenesis, and cancer cell survival by accumulating CDK inhibitors. This was hypothesized to be related to the crypt-villus cell renewal impairing and shedding the epithelia (Nougayrède et al. 2005).

Figure 6: The amide functional group.

The CNF1 stimulates the transcription of genes and cellular proliferation via Rho GTPases situated in the cytosol and plasma membrane (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones and Luria-Pérez, 2019; Nougayrède et al., 2005). The CNF1 has enzymatic activities that convert glutamine 63 of RhoA to glutamic acid (Schmidt et al., 1997). CNF1 also targets Rac1 and Cdc42. They have AB toxins that interact with cell surface receptors and this affects intracellular signaling in host cells (El-Aouar et al., 2017).

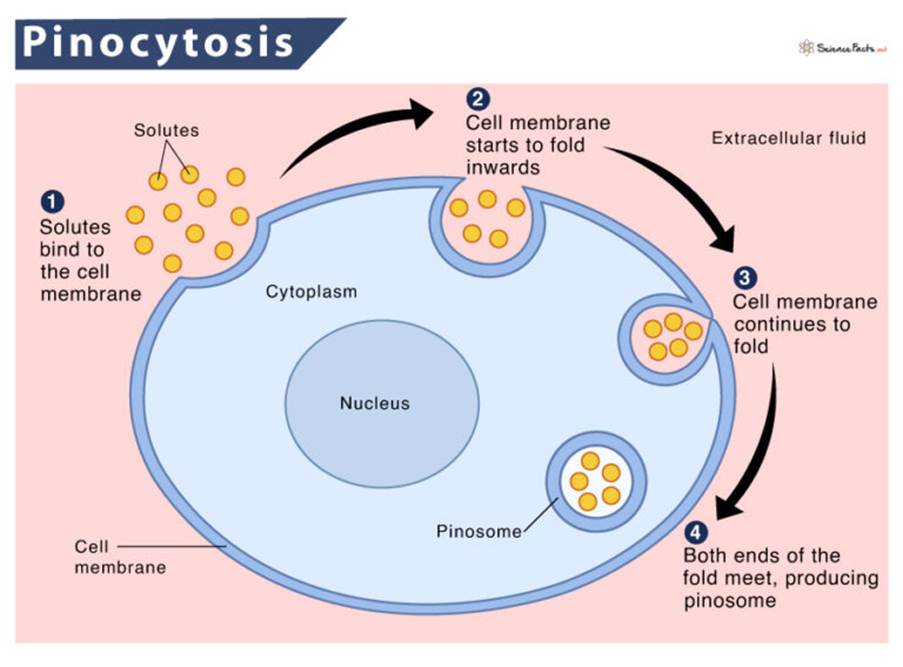

Other mechanisms include the processing of CNF-1 by the enzyme endosomal protease for regulation, cell motility, and the ability of white blood cells (polymorphonuclear leukocytes) to bind to the epithelium. The activation of Rho GTPases increases apoptosis and micropinocytosis – please see Figure 7 (El-Aouar Filho et al., 2017).

CNF-1 can dysregulate the cell cycle, especially in the G2 to M phase by downregulating cyclin B1 expression, sequestering it in the cytoplasm, and preventing CDK1 from functioning. Uroepithelial cell analysis presents Cyclin B1 resides in the cytoplasm before being translocated to the nucleus to proceed with the breakdown of the nuclear envelope (Falzano et al., 2006). This favours E. coli colonization, invasion, metastasis, and motility and evades the clonal expansion and function of lymphocytes (El-Aouar et al., 2017). The aberrant expression of Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF) influences the colonic epithelial barrier (Hajishengallis, Darveau, and Curtis, 2012).

Figure 7: The process of pinocytosis

Example Two: Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF)

Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) is an obligate, anaerobic gram-negative bacteria that makes up 0.1% of the normal flora of the colon – please see Figure 8 (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023). Some sources suggest that the ETBF accounts for 0.5% to 2% of the whole human intestine (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, Luria-Pérez, 2019). On the other hand, patients with colorectal cancer had high levels of this bacterial strain in the faeces and colon mucosa in the early stages (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, Luria-Pérez, 2019).

Figure 8: Bacteroides fragilis

How does ETBF cause infection and bowel cancer?

ETBF releases the metalloproteinase enzymes, also known as B. fragilis toxin (BFT) or fragilysin. BFT is a multifunctional protein that can induce and promote cancer progression. It can attach to receptor proteins on the epithelial lining of the colon. The cancer cells can grow by cleaving the protein E-cadherin in the gap junctions (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, Luria-Pérez, 2019; Elsalem et al., 2020; Sears et al., 2008; Elsaghir and Reddivari, 2022). This halts the adhesive properties and affects the structure of the colon epithelium.

Another mechanism of ETBF toxin-mediated carcinogenesis is activating c-Myc. This increases the expression of spermine oxidase (SMO). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in the form of superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and peroxynitrite (PNT) (ONOO−). This enhances oxidative stress and carcinogenesis (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, Luria-Pérez, 2019).

ETBF recruits and accumulates T lymphocytes in the intestinal lamina. BFT can induce an inflammatory response by polarising the Th17 lymphocyte response and increasing the secretion of interleukin 17 (IL-17) (Hajishengallis, Darveau, and Curtis, 2012). This can trigger tumourigenesis and inflammation and is suggested to be related to the activation of STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in colon cancer and irritable bowel disease (IBD) patients. BFT can stimulate NF-κB-dependent expression of chemokines and activate neutrophil transepithelial migration (Hajishengallis, Darveau, and Curtis, 2012). Non-toxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (NTBF) expresses polysaccharide A, a symbiosis factor that prevents Th17 pro-inflammatory response (Hajishengallis, Darveau, and Curtis, 2012). This demonstrates how NTBF and ETBF can elicit their mechanisms on Th17 with contrasting effects.

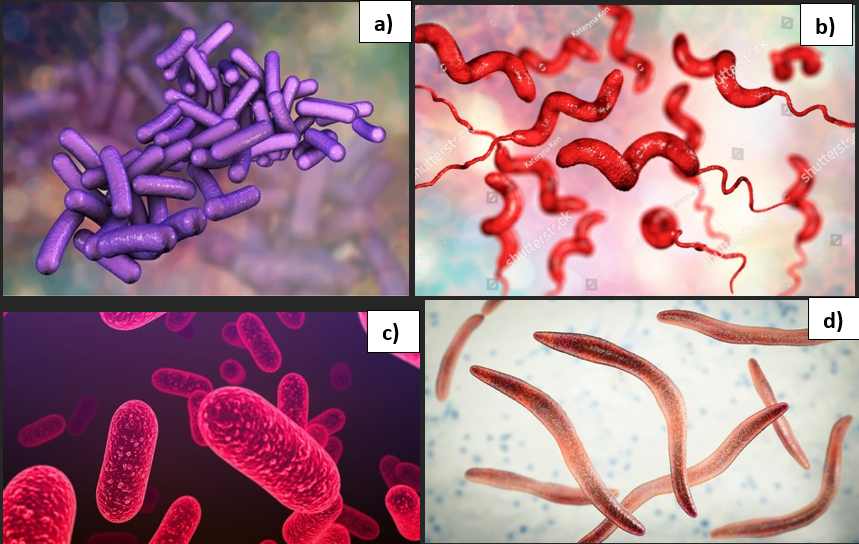

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) can suppress the immune response and increase cancer growth. IL-17 can upregulate chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5) and insert MDSC into the tumour tissue. This supports the generation, differentiation, and development of MDSC in the bone marrow (Li, Garstka and Li, 2020). MDSC produces several immunosuppressive factors by ROS and potent metabolic enzymes: nitric oxide synthase and arginase I. This prevents the proliferation of T lymphocytes and Natural killer cells (Hernández-Luna, López-Briones, Luria-Pérez, 2019). Other pathogenic bacteria that promote bowel cancer progression are illustrated in Figure 9. Therefore, members of the gut microbiota have oncogenic potential by modulating the inflammatory response and signaling pathways via their virulence traits to upsurge the rate of colon carcinogenesis.

Figure 9: Pathogenic bacterial strains

a)Shigella dysenteriae b) Campylobacter jejuni c) Salmonella typhi d) Fusobacterium nucleatum.

New risk factor two: Antibiotics can increase the risk of bowel cancer.

The emergence of antibiotics in 1928 has ushered in a phenomenal impact on the treatment of infectious diseases caused by bacterial pathogens. It has extended the half-life of people by 23 years but since 1950, there was a gradual reduction in producing new antibiotics because overuse increased the prevalence of bacterial resistant infections. It is estimated that by 2050, the mortality linked to drug-resistant infections will exceed 10 million (Aranda and Rivas, 2022). Recent evidence discovered their use in causing an imbalance of microbial composition and lowering bacterial diversity in the gut microbiome which is referred to as dysbiosis. Dysbiosis can reprogramme energy metabolism and modulate immune regulation increasing risks of both benign and malignant colorectal tumours (Liu et al., 2025). Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide affecting ca. two million people (Abedizadeh et al., 2024; Gonzalez-Gutierrez et al., 2024). Therefore, researching ways to lower risk is essential to lowering the rate of cancer incidence.

The classification and role of antibiotics

Antibiotics are organic chemical compounds that are classified based on several principles: molecular structure, mechanism of action, type of bacteria they target, and method of administration (Aranda and Rivas, 2022). Some antibiotics are natural whereas others are semi-synthetic or synthetic where they can either be administered as a topical cream, swallowed orally, or applied parentally (Aranda and Rivas, 2022)

The spectrum activity of antibiotics is dichotomized into narrow and broad-spectrum. Broad-spectrum antibiotics target a large subset of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Amongst the examples of broad-spectrum antibiotics are tetracyclines imipenem and third-generation cephalosporins. In contrast, narrow-spectrum antibiotics target gram-positive bacteria and are notably penicillin and first-generation cephalosporins.

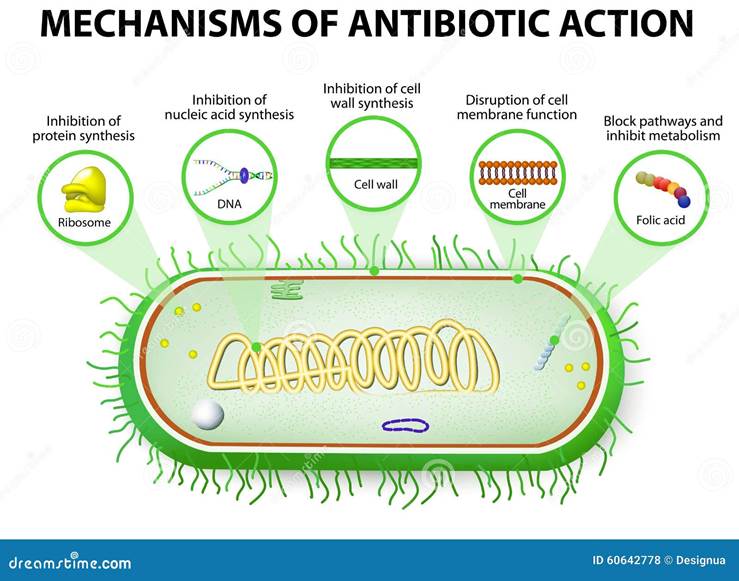

There are various mechanisms of action in the antibiotic response towards bacteria – please see Figure 10a. Some antibiotics inhibit the bacterial cell wall, for instance, β-lactams, bacitracin, glycopeptides, and Fosfomycin. Beta-lactam penicillin irreversibly inhibits the bacterial enzyme transpeptidase involved in cell wall synthesis by covalently binding to the active site of the enzyme (Dimitrakopoulou et al., 2012; Dousa et al., 2022). Some antibiotics target the ribosomes consisting of two subunits: 50S and 30S RNA and this is where protein synthesis takes place (Crowe-McAuliffe and Wilson, 2022). Inhibitors of the 50S are tetracyclines, macrolides, and aminoglycosides. Inhibitors of the 30S are tetracyclines, nitrofurans, aminoglycosides, and spectinomycin (Aranda and Rivas, 2022).

Other antibiotics prevent nucleic acid synthesis, for instance, topoisomerases, quinolones, fluoroquinolones, nitrofurans, and sulfonamides (Kümmerer, 2009). Quinolones target the DNA gyrase and key examples are ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, and novobiocin. Some inhibit the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, for example, Rifampicin and streptovaricins.

There are additional mechanisms of antibiotics, for instance, inhibitors of the cell membrane and synthesis like lipopeptides and polymyxin B and E (Jiang et al., 2022). Inhibitors of folate synthesis, sulphonamides compete with para-aminobenzoic acid. This prevents the production of folic acid (Aranda and Rivas, 2022). Some are involved in RBA elongation like actinomycin. This illustrates the various mechanisms of antibiotics.

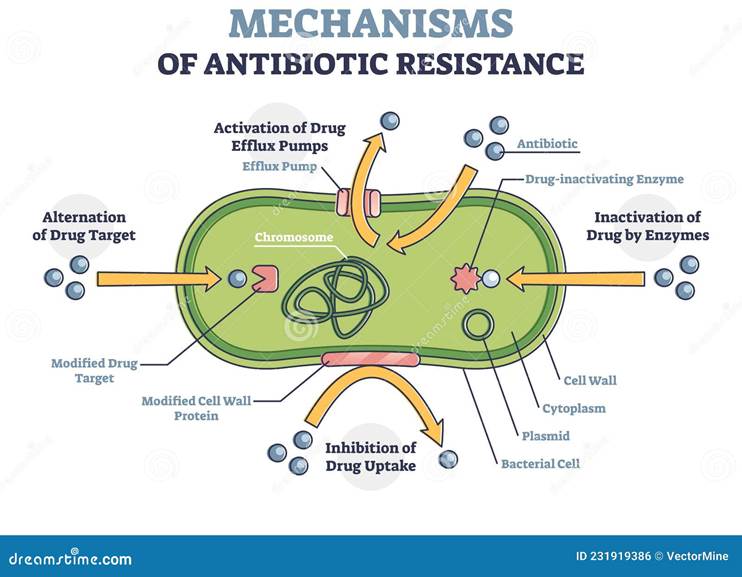

However, resistance can be a direct result of the overuse of antibiotics, not completing the course of treatment, competition between microorganisms in the environment, and spontaneous mutations that give rise to adaptations (Waglechner and Wright, 2017). This can increase the risk of bacterial pathogens to survive and develop resistance. Among the resistance mechanisms are preventing drug uptake, inactivating drugs via enzymes, altering the drug target, and activating drug efflux pumps – please see Figure 10b. This demonstrates how resistant and non-resistant bacterial strains can alter the function of the antibiotics.

Figure 10: Normal and resistant mechanisms of antibiotics

The link between antibiotics and colon tumourigenesis

The relevance of antibiotics use as a risk of colon cancer has sparked interest but the underlying mechanism remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that the tumourigenic role of antibiotics increases the risk of bowel cancer depending on the anatomical site, type of antibiotic regimen, and dose-dependent fashion (Nelson and Wiles, 2022). This has been predominantly observed in patients treated with penicillin and cephalosporin (Zhang et al., 2019). Other researchers detected the oncogenic potential of broad-spectrum antibiotics, quinolone, trimethoprim, and sulfonamide (Petrelli et al. 2017). There have been several exploratory studies discussing the link between the factors.

Zhang et al. (2019) conducted a case-control study between 1989 and 2012 where 28980 colorectal cancer cases and 130077 were identified. The risk of colon cancer was detected after a minimal dose and was higher in the proximal colon site (ptrend=0.001) upon treatment with penicillin, and amoxicillin, where the Odds Ratio (OR) was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.05 to 1.13) but inversely associated in rectal cancers (ptrend=0.003) upon treatment with tetracyclins where the OR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.97) despite antibiotic exposure, exceeded more than 60 days. They also discovered there is a higher risk of proximal colon cancer and an odds ratio of 1.17 for antibiotic exposure compared to no exposure more than a decade before cancer diagnosis (Nelson and Wiles, 2022). This demonstrates have tetracyclines have an anti-inflammatory effect and disrupt gut microbiota in the rectum lowering tumourigenesis (Lui et al. 2025. These interesting results are attributed to the bacterial adaptations and variations in microbiota concentration in the colon and rectum. It has been hypothesized that because the antibiotics are not fully absorbed by the small intestine; antibiotics can bypass the initial segment of the colon. Alternatively, the gut microbiota plays a role in loosening the toxic effects of antibiotics and degradation where by the time it reaches the distal colon, the overall effect of antibiotics diminishes (Nelson and Wiles, 2022). This heterogeneity may suggest there are differences in the gut microbiota and mechanisms of carcinogenesis in the lower gastrointestinal tract and dependent on the anatomical site. Moreover, there is potential to remove harmful bacteria near the vagina due to close anatomical proximity (Nelson and Wiles, 2022). Other potential reasons for the discrepancy are the strength of metabolic activity and high microbial density (Nguyen et al., 2022; Mima et al. 2016).

Meta-analysis studies by Liu et al. (2025) revealed that 13% of subjects had an elevated risk of colon cancer post-antibiotic treatment following the analysis of twenty-three studies that included 1, 145, 853 patients. The OR was 1.13 upon antibiotic exposure regardless of whether the pathological stage was benign or malignant. Another independent factor was a follow-up period where inadequate follow-up > 5 years truncated significantly with tumour risk and propagated negative outcomes. In contrast, shorter follow-up periods were inversely proportional because the latency period was estimated to be 8-10 years for colorectal cancer (Wang et al., 2014). The increased risk was substantially enhanced during combined antibiotic therapy than monotherapy and upon upsurging the duration post-antibiotic exposure.

On the contrary, several limiting factors may affect Lui et al. (2025) findings: the body mass index (BMI), sex, and age were not explored. These confounding factors alongside lifestyle risk factors, exposure to pollution, and other environmental conditions or comorbidities may influence the microbiome status, baseline, and cancer potential. There were minimal control variables where there was variation per study in the type of study design, estimates, type of antibiotics, the concentration of the dose, duration of the exposure, frequency of the dose, method of administration, timing, and location, and could affect the study conclusions. However, the robustness of Liu et al. (2025) findings is surpassed by the subgroup and sensitivity analysis.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Petrelli et al. (2019) helped overcome these limitations by Liu et al. (2025) and was considered the largest study. They explored 7,947,270 adult subjects from 25 observational studies who were exposed to antibiotics for infections and analyzed the cancer incidence in solid tumours and lymphomas. They reported similar findings to Zhang et al. (2019) where longer duration of antibiotic exposure and/or high doses had a higher rate of cancer diagnosis. However, the 18% increased risk was not solely to colon cancer but other cancers. There was a 30% increased incidence of antibiotic-induced secondary cancers of the blood, lung, pancreas genitourinary, and blood notably multiple myeloma and lymphoma compared to the control (Petrelli et al. 2019). There were contrasting results with previous studies where there was a small increase in the colon (8%), stomach (6%), and melanoma but no link with oesophageal and cervical cancer (Petrelli et al., 2019).

There is also a potential risk of forming secondary tumours because of an imbalance of harmless and pathogenic bacteria. This is referred as dysbiosis and can appear in the lung (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03–1.61, p = 0.02), kidneys (OR 1.28, 95%CI 1.1–1.5, p = 0.001), pancreas (OR 1.28, 95%CI 1.04–1.57, p = 0.019) and blood cancers, notably multiply myeloma (OR 1.36, 95%CI 1.18–1.56, p < 0.001) and lymphoma (OR 1.31, 95%CI 1.13–1.51, p < 0.001) (Nelson and Wiles, 2022; Petrelli et al., 2019). These ORs were higher in comparison to colon cancer (OR 1.08, 1.007-1.17, p < 0.03) and stomach cancer (OR 1.06, 1.02-1.1, p < 0.001). Despite the intensification, efforts, and the number of participants that strengthened the study, Petrelli et al. (2019) acknowledged several discrepancies. There is a significant difference between individual participant data analysis and study level analysis and should have been optimally combined across multiple studies and include time-to-event analysis. Lifestyle factors (diet, exercise, health status) and environmental factors are unknown whether they contribute to carcinogenesis. Seven of the studies did not include the classification of the antibiotic nor the pathological status of the cancer where early stage or late stage and when diagnosed contribute to the outcome. Twelve studies did not report the follow-up period. There was minimal ethnic diversity and one study included patients of Asian heritage (Petrelli et al., 2019).

There are fluctuations in the use of OR value as a statistical measure to determine the link between antibiotic exposure and bowel cancer where it rests between 1.09. 1.13, 1.08 in the aforementioned studies. Nevertheless, there is agreement that in all cases, antibiotic use is directly proportional to colon carcinogenesis. Exploring the reasons for this outcome could be associated with the regulatory mechanism of gut microbiota in the colon. On one hand, the commensal flora pivotally digests, produces, and absorbs nutrients, namely lipids, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and bile acids (Petrelli et al., 2019). It also prevents the colonization of pathogenic strains by producing bacteriocins and limiting the availability of nutrients for their survival which helps enhance and maintain the structure and physiological function of the intestinal epithelial lining.

On the other hand, the gut microbiome may lose its functional potential and resistance mechanisms when antibiotics are consumed modulate the gut microbiome interaction with the immune system, and propagate inflammation and growth and proliferation of pathogenic bacterial strains and colon cancer cells (Petrelli et al., 2019). The Fusobacterium and E. coli species were associated with colon cancer whilst Helicobacter pylori was linked with gastric cancer. Moreover, antibiotics lower the efficacy of cancer patients who undergo immunotherapy causing poor prognosis. Therefore, the removal of pathogenic strains enhances the sensitivity of tumour cells toward treatment. Overall, these research studies illustrate that modulation in the gut microbiota concomitantly with lifestyle factors is embedded in the pathogenesis of inflammation and colon cancer and other types.

New risk factor three: Cystic fibrosis can increase the risk of bowel cancer.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a complex genetic condition derived mutated form of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that regulates chloride ion transport (Parisi et al. 2023). A gene is a short section of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that contains instructions on how to encodes a particular protein (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). Changes in the gene are referred as mutations where the mutated CF affects a range of organs predominantly the digestive system and the lungs. Advancement in medical treatment and tailored screening protocols has increased the life expectancy through early detection. However, there is a rise of speculation that CFTR has a double-edge sword in induced CF pathogenesis and develop and progression cancers in CF patients. Understanding the normal and pathological function of CFTR and the classification system of CFTR mutations can facilitate in the development of new therapeutic drugs like highly effective CFTR modulator (HEMT) therapy that have a personalised approach in patients with CF-related cancers.

What is CF?

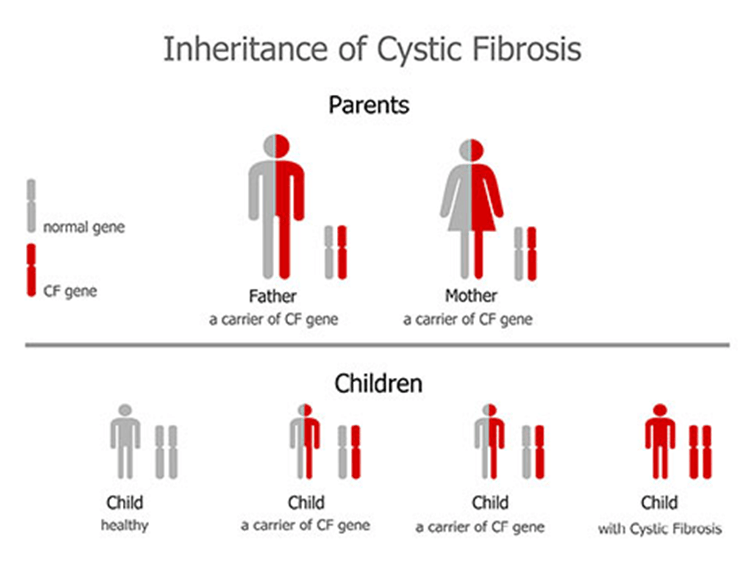

CF is caused by the abnormal functioning of the CFTR protein (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). It is an autosomal recessive disease, so both parents must carry the CFTR mutated gene that encode for the mutated protein for the progeny to be diagnosed with CF, if only one is present then the individual will be a carrier (Parisi et al., 2023). Please see Figure 11. Each child has 25% (1 in 4) chance of being diagnosed with CF.

Figure 11: Genetic inheritance of cystic fibrosis (Creative Commons, 2025)

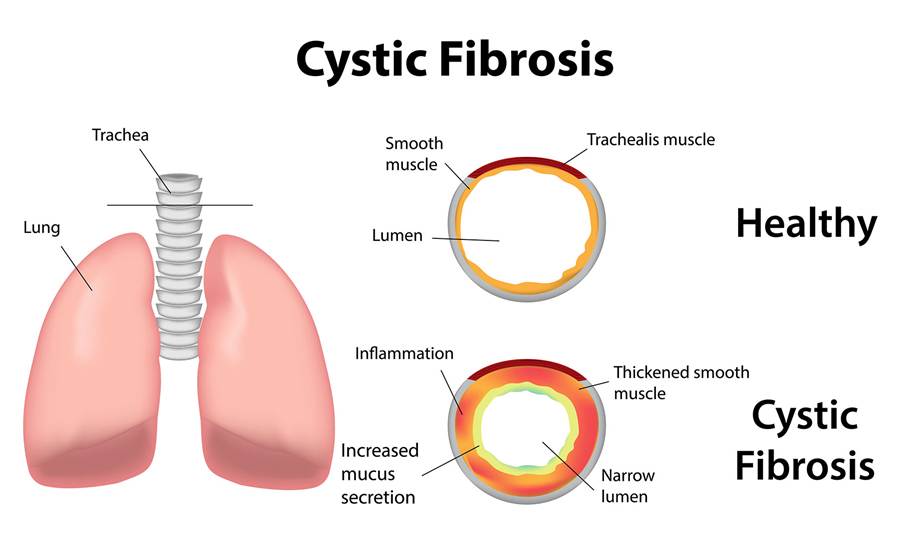

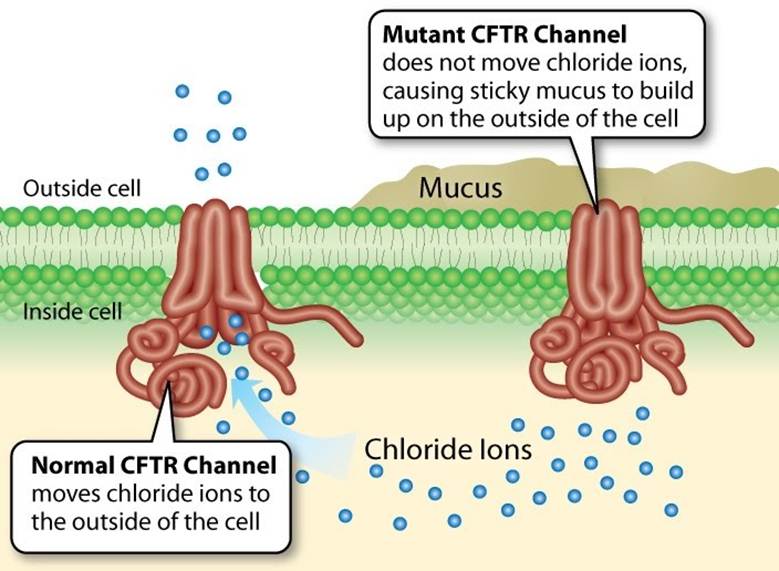

CF is characterized by the production of thick, sticky mucus that can obstruct the airways leading to recurrent infections and lung dysfunction – please see Figure 12. Secretions in the digestive glands are also impaired influencing the rate of digestion and absorption (Parisi et al. 2023). The normal function of CF protein serves as a chloride channel that regulates the movement of chloride ions and water molecules outside the cell and across apical membranes of epithelial cells – please see Figure 13 (Parisi et al., 2023). Increased sodium absorption via the epithelial sodium ion (Na+) channels (ENaC) and NA/K ATPase pumps present in the basolateral membrane also occur (Cystic Fibrosis Medicine and Cystic Fibrosis Online, 2021).

An abnormal CFTR channel blocks the ion transport due to the presence of mucus. This can alter cellular homeostasis, where the balance of intracellular chloride and bicarbonate ions affects the cellular pH and metabolic processes (Lu et al., 2012). Alterations in ion transport and abnormal CFTR protein can also progress to a net increase in water absorption, low surface fluid in the airway, defective adhesion of bacteria to the membrane, and impair the function of cilia hair to remove the mucus and gram-negative bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Cystic Fibrosis Medicine and Cystic Fibrosis Online, 2021).

Dysfunction of the CF protein, chronic inflammation, dysregulation of the immune system, and gut dysbiosis can exacerbate the symptoms experienced in CF and are implicated in cancers, where a pro-tumourigenic microenvironment and inflammatory mediators of cytokines and chemokines can drive cancer cell proliferation, DNA repair, and evasion of apoptosis to promote cancer progression (Murphy and Ribero, 2019). Epidemiological evidence indicates that the increase in colorectal, breast, pancreas, and lung cancer incidence is more apparent in patients with CF than in non-CF status (Appelt et al., 2022).

Figure 12: The effect of mutated CF on the airways in the lungs (Creative Commons, 2025)

Figure 13: The normal and abnormal CFTR channel (Creative Commons, 2025)

Mutations of CFTR and the classification system

Mutations Of CFTR And The Classification System

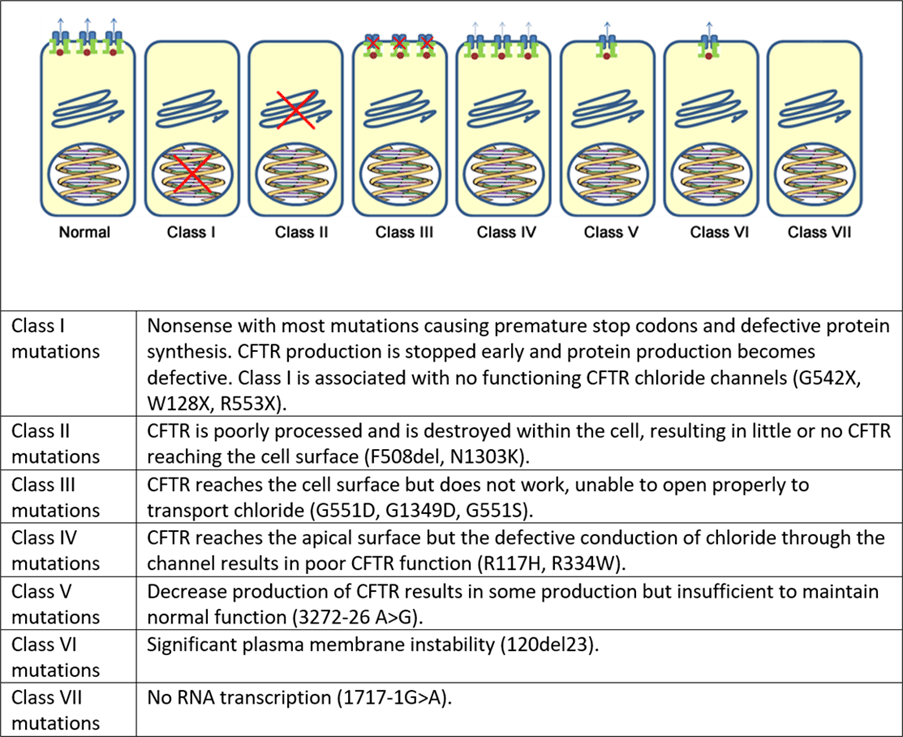

The CFTR protein is encoded by the CFTR gene that was discovered in 1985 to be localized to 7q21-34 on the long arm of chromosome 7 (Wainwright et al., 1985). The genetic sequence was identified in 1989 and revealed the CFTR protein contains 1480 amino acids (Rommens et al., 1989; Riordan et al., 1989; Kerem et al., 1989). Over 1,200 mutations have been linked to CF but the most common is deltaF508 which is a 3-base pair deletion of amino acid phenylalanine. They are primarily considered a type of protein-processing mutation (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). It accounts for 76% of affected chromosomes in the UK. The traditional classification system that characterizes CFTR mutations is subdivided into six classes. They vary in the efficiency of CFTR protein synthesis from not forming the protein to a malformed CFTR protein with quantitative or qualitative changes in CFTR function (Cystic Fibrosis Medicine and Cystic Fibrosis Online, 2021). These are summarised in Figure 14 and Supporting Material 1.

Figure 14 The functional classes of CF mutations (Cystic Fibrosis Medicine and Cystic Fibrosis Online, 2021)

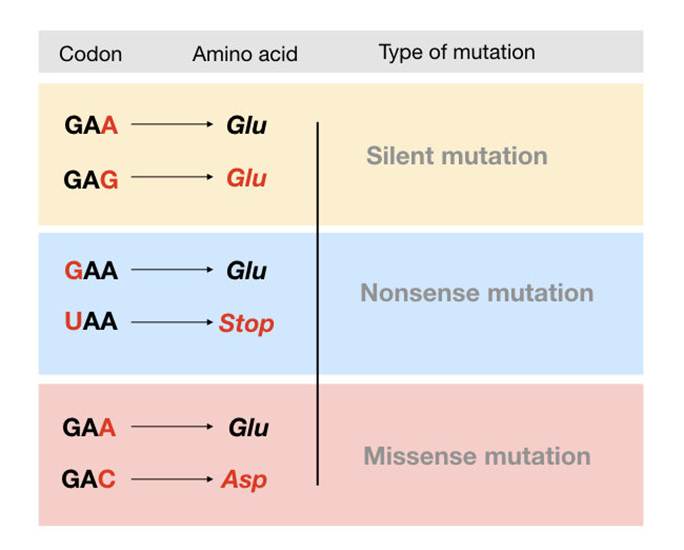

The first class of CFTR mutations (I) are associated with protein production. It encompasses non-sense and splice mutations where there is a premature or early stop codon – please see Figure 15. The non-sense mutation is a type of point mutation often referred to as single nucleotide polymorphism where a single base is affected. It is commonly caused by an error in DNA replication that takes place in the S phase of the cell cycle where the genetic material is doubled. The enzyme DNA polymerase helps insert nucleotides to grow DNA strands but sometimes misses or inserts the wrong nucleotides or letters. This increases the risk of replication errors and is normally corrected through the proofreading status where DNA polymerase corrects the error (Chauhan, 2019a).

The normal function of the stop codon serves as a ‘stop signal’ where the CFTR gene that has instructions on the order of the amino acid has reached the end of the sequence and can stop making the protein (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). Amino acids are the building blocks that make up a protein. The three types of stop codons are UAA, UAG, and UGA. Point mutation leads to the production of unstable mRNA or the release of incomplete proteins that are not functional. This protein is degraded before it can reach the membrane. The phenotype of patients carrying the stop mutation is severe.

Simultaneously, splice mutations affect how the gene correctly reads the instructions to make the CFTR protein by changing the signal and giving irrelevant letters or missing relevant letters in the instructions at either the beginning or end of the sequence (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). This affects the production of the CFTR protein.

Figure 15: Types of point mutations (Chauhan, 2019a)

In Class Two, CFTR protein is unable to fold due to the deltaF508 mutation where the amino acid is deleted. This affects the 3D shape and stability influencing its ability to transport chloride ions (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). The cell becomes aware that the protein is not in the right shape and is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and eventually targeted for degradation.

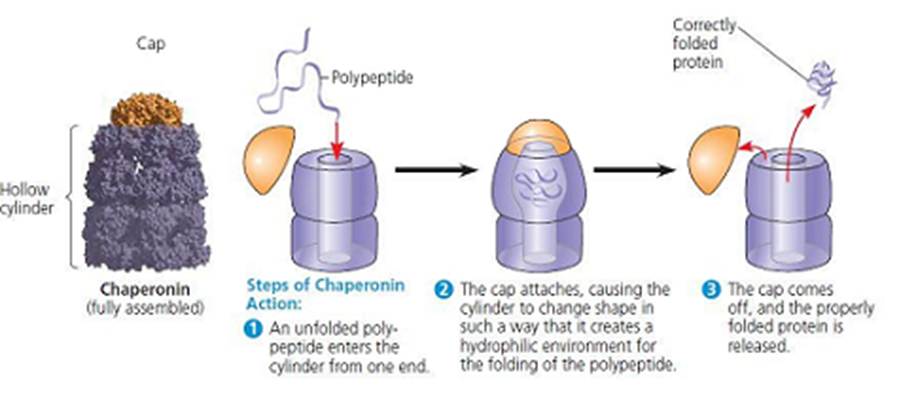

Normally, CFTR translates into a peptide in the ribosome and undergoes a series of processes in the ER and Golgi apparatus. Both organelles are involved in protein processing and transport. These processes may include glycosylation (the addition of a sugar group) and folding by chaperone proteins that enable the trafficking of CFTR to the apical cell membrane – Figure 16. Chaperonin proteins, Hsp 60 and Hsp 10 are a type of chaperone protein that can recognize and correct a misfolded protein to restore native folding structure but do not assemble protein during synthesis as opposed to other chaperone proteins (Tamashiro, 2023). Pharmacological studies revealed the drug, Trikafta that consists of elexacaftor, tezacaftor and ivacaftor help overcome the misfolding to allow chloride ions to pass through but is not fully amended.

Figure 16: The function of chaperonin (Tamashiro, 2023)

The third class of the CFTR mutational classification system is referred to as gating mutations. The shape of the CFTR protein resembles a gate to allow chloride ions to enter. If the gate is locked, chloride is unable to do so. Drugs like ivacaftor help to keep the gate open and reduce CF symptoms.

Phosphorylation (the addition of the phosphate group) of the CFTR protein by protein kinase (PK) and dephosphosphorylation (removal of the phosphate group) by protein phosphatase (PP). This is vital in regulating the CFTR chloride channel activity. Phosphorylation of the regulatory domain causes the energy source, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to bind to the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD). This results in the induction of chloride transport. Therefore, the Class 3 CFTR is produced, processed transported, and inserted into the apical membrane, however, phosphorylation or binding of ATP does not occur (Cystic fibrosis, foundation, n.d.).

On the other hand, conduction mutations in the fourth mutational classification are where the CFTR protein is produced in the right 3D shape despite the change in one amino acid. It also undergoes processing, and transport to the apical membrane and performs phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. However, it does not function well and slows the rate of chloride transport because of a change in one amino acid (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, n.d.). Some mutations alter the shape inside the channel and chloride ions are unable to move easily.

The fifth class of mutations is the insufficient normal CFTR proteins caused by several factors: limited production, a small number of protein functioning, rapid protein degradation, and small proteins remaining behind. This can be associated with the generation of abnormal and correctly spliced transcripts. These patients have a mild phenotype but with variable disease expression depending on the level of correctly spliced transcripts (Marson, Bertuzzo, and Ribero, 2016). The sixth class is related to the instability of the plasma membrane.

However, recent changes to the CFTR mutation classification system by De Boeck and Amaral (2016) divided class I into class I stop codon and a new class, seven (VII) characterized by no mRNA transcription to improve drug development. Both have equivocal outcomes where the CFTR protein is missing. Critics like Marson, Bertuzzo, and Ribeiro (2016) claim it does not take into consideration the severity of the CFTR mutations because class seven may be the last mutation but has been associated with more severe mutation classes of I, II, and III rather than its original mild phenotypic trait.

To overcome this limitation, Marson, Bertuzzo, and Ribero (2016) postulate a new model where each CFTR mutation alongside its severity feature and recommended therapy has been instilled into the design. Class I is subdivided into Class IA and Class IB formerly Class VII and Class I respectively. In Class IA, it is characterized as having no mRNA and unavailable corrective therapy. This allows the continuation of the mutation. In recent years, the aim has been to introduce therapies with the hope of treating the mutational status. On the contrary, Class IB contains no protein and has available corrective rescue synthesis due to its severity. A summary of current therapies is found in the Supporting material below.

Supporting Material for CFTR Mutations

Current diagnostic methods for detecting CF

To diagnose a baby with CF, the first test performed is the neonatal screening which was placed in October 2007 (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.). During the first two weeks of a child’s life, high levels of immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) levels indicate CF is present. IRT is measured on a dried blood spot on the Guthrie card on Day 6 of life (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.). The blood sample is taken from the child’s heel and the level of this pro-enzyme is monitored. Some children may need a second heel prick. The CF Nurse Specialist arranges a joint visit to the family within five working days, either on a Monday or Wednesday, where a sweat test is performed on either Tuesday or Thursday (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.).

Sweat Tests

The sweat test is a mandatory test to determine if the CFTR genes are present, ruling out false-positive screening results in newborn screening. It has a sensitivity of 98% and can be done when the baby is >48 hours old. It can also measure the sweat volume and chloride ions. To confirm CF diagnosis, two sweat tests are taken using the Macroduct system from different limbs to increase reliability. The normal range of chloride ions is 60 mmol/l. The borderline chloride ions are between 30 to 60 mmol/l, however, this range may still indicate CF. A chloride ion level beyond >60 mmol/l confirms CF diagnosis.

Diagnosis and results are commonly confirmed by the paediatric consultant with the family who can ask questions. A treatment pathway for CF is organised following a meeting with the Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) and parents. If levels are high, other genetic tests can be carried out to find out exactly which mutations are present and detect the severity of the disease. This test is not reliable after two weeks of birth as several other factors may contribute to the high levels of IRT (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.).

Genetic Tests

This type of test is commonly performed because of the high number of identified variants of the CFTR gene. Cord blood testing is planned for newborn siblings at the time of birth. Older siblings will have a sweat test rather than genetic analysis for diagnosis. The aim is to detect carriers of the mutated CFTR gene and should be postponed until the sibling is at a mature age before knowing their carrier status (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.). Genotype analysis will not be used to guide prognosis unless it is associated with pancreatic sufficiency (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.).

PCR Analysis

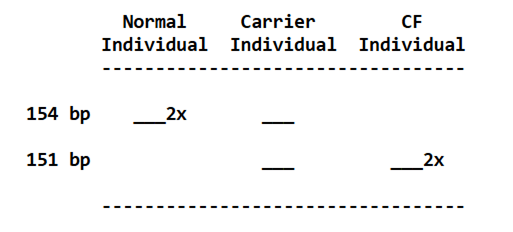

One of the first genetic tests that can be carried out for the diagnosis of CF is Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis. There are two types of PCR: conventional and real-time PCR. Conventional PCR analysis provides a qualitative or visual analysis of whether the most common mutation (deltaF508) is present by the location of the ‘band’ on an agarose gel. Agarose is a sugar molecule (polysaccharide) extracted from seaweed. A conventional PCR has two controls as references alongside the DNA markers: positive control (CF target gene present) and negative control (CF target gene absent). A deletion of 3 base pairs (bp) suggests a CFTR mutation. PCR was developed to determine whether the normal gene is distinctive from the mutant gene (McClean, 1997).

There are two products synthesized from the primers and contain distinctive bands: 154 bp indicates a non-CF status whereas 151 bp confirms CF. If both genes are presented there will be two bands. If one band is present, it may suggest the second gene is of different mutational status and requires alternative genetic tests (McClean, 1997). Please see Figure 17. Female eggs were fertilised in vitro and embryos developed to the eight-cell stage. A single cell was removed and the DNA was analyzed via PCR. Two embryos (x2) have bands in position 151 bp indicating CF status. Two embryos (x2) have bands in position 154 bp presenting non-CF. A carrier status has a band at 151 bp and 154 bp. A baby weighing 7 pounds (lb) and 3 ounces (oz) was born to the couple (McClean, 1997). This demonstrates the sensitivity of the instrumental technique to detect CFTR mutations.

Figure 17 Example of a PCR analysis

Real-time PCR

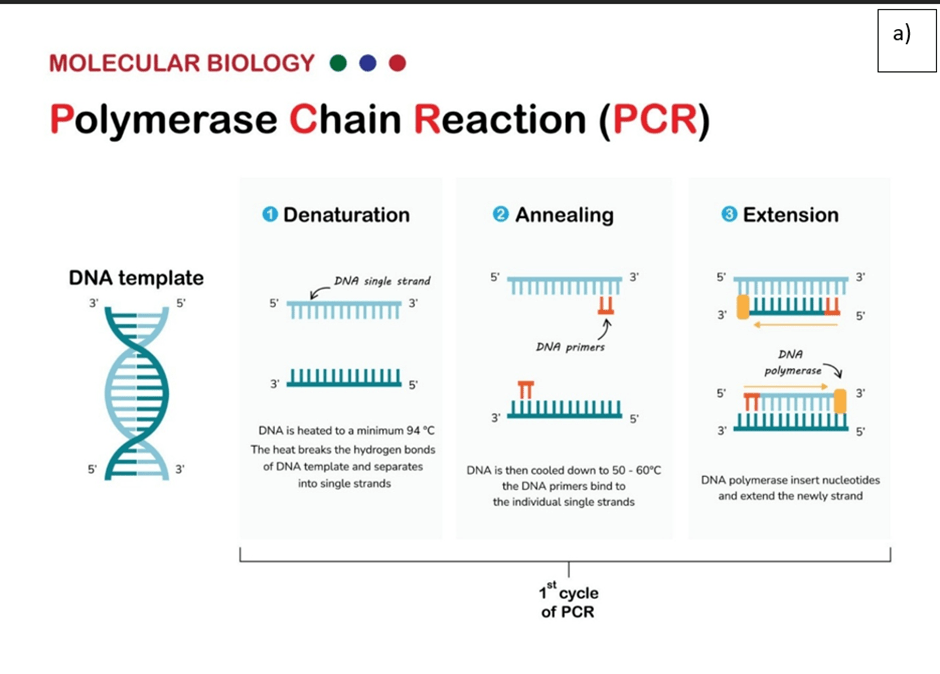

Real-time PCR (qPCR) provides amplification and analysis of the target DNA product. The general principle involves the use of Fluorescent dye like SYBR green which reacts with amplified products and can be used to detect the target nucleic acid as the reaction progresses, in real-time, with product quantification after each cycle (Tankeshwar, 2025). There are several reference genes used as quality control to determine the success of qPCR like Beta-actin. There are three stages involved in qPCR per cycle and vary with temperature ranges: denaturation of mRNA, annealing with primers, and extension by DNA polymerase such as Taq that adds free nucleotides – please see Figure 18a. (Tankeshwar, 2025).

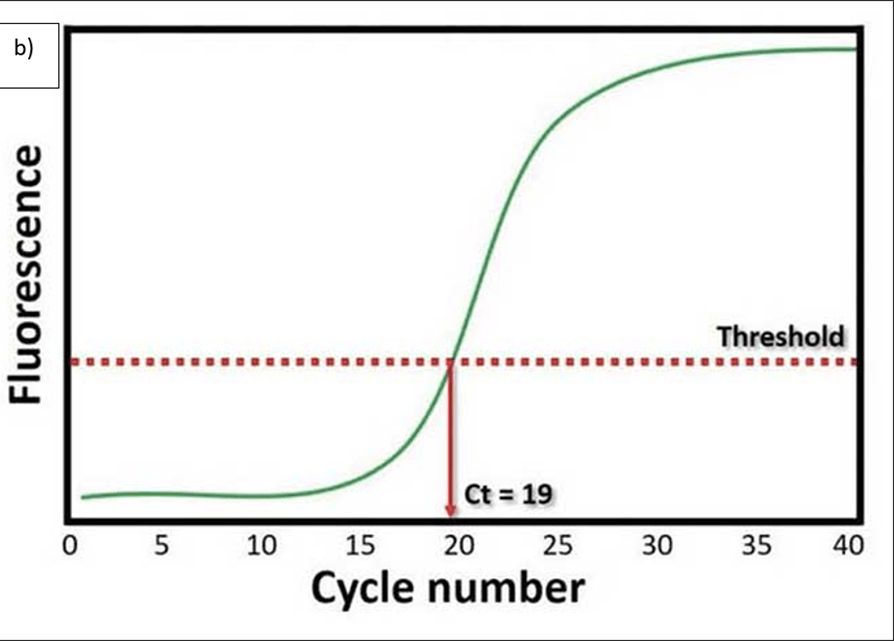

A graph is plotted based on the product formed over time – please see Figure 18b. The cyclic threshold (Ct) value indicates how many cycles of amplification for the target DNA or RNA to form sufficient fluorescence to cross the set threshold (Figueredo Lago et al., 2017; Figueredo Lago et al., 2015; Chauhan, 2019b). The threshold is presented as a line for the detection level at which a reaction achieves fluorescent intensity above background levels (Chauhan, 2019b). Normally, PCR uses 40 cycles amplification where each cycle doubles the target DNA. 3.3 cycles is estimated to serve a 10-fold change. A low Ct value indicates a high concentration of the target whereas a high Ct value implies a low concentration. A Ct value of the mutant PCR indicates one mutation while a change in the Ct value (ΔCt) suggests the number of affected alleles (1 or 2). This method helps detect patients of a carrier status when analyzing multiple mutations and does not leave the reaction tube which lowers the risk of contamination (Figueredo Lago et al., 2017; Figueredo Lago et al., 2015).

Figure 18 Real-time PCR general method and example of the amount of target product produced.

Amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS)

Another test that can be performed is the amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS). It can help detect the most common CF mutations. In this technique, three multiplex PCR reactions are performed in parallel for each individual. Each tube contains several separate primers capable of detecting different mutations. The primer pairs per tube anneal a specific allele to produce a distinct band. A band is only made in the presence of a mutant allele whilst a non-mutant allele is absent. Positive control determines whether the PCR reaction is functioning appropriately. This technique is preferred because of its accuracy and speed of detection. However, it cannot be used to distinguish between homozygotes and heterozygotes except for the DF508 mutation; therefore positive signals are easily differentiated to identify the exact mutations present in carriers and non-carriers (Richards et al., 2002; Figueredo et al., 2015).

Multiplex Allele Specific PCR

A DNA synthesizer produces short synthetic DNA sequences (oligonucleotides) that are complementary to the normal DNA sequence. This is referred to as Allele Specific Oligonucleotides (ASO). The oligonucleotides are then fluorescently or radioactively labeled and then probed to a patient or control DNA. During hybridization, the oligonucleotides bind specifically to a perfect complement sequence that has no mismatched base. This suggests oligonucleotides can only bind to normal DNA. This helps to distinguish between normal and mutant DNA (Adkinson, 2012). For example, ASO can hybridize with the CFTR gene that contains the mutation. The oligonucleotide cannot bind to normal DNA because it has a deletion. A mutation-specific ASO can be used to screen for the presence of the CFTR mutation and distinguish between homozygous, heterozygous, and wild-type subjects (Adkison, 2012).

There are several limitations of mutational analysis: the number of genetic variations related to CF. The most common is the R117H-7Y essential 7T/5T variant. It is found in non-CF with F508del mutation. The first-line screening entails the 50 most common gene variants. Failure to detect does not exclude diagnosis especially if the child is non-Caucasian. A specific panel of gene variants was created that intersects with ethnic origins common in the Asian community. Alternative genetic tests take place at an antenatal period where genetic counseling is given ca. 10-12 weeks gestation.

Other diagnostic tests

Furthermore, additional tests can be performed to detect CF. People with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) and CF have low levels of the enzyme elastase in their stools. EPI is characterized by low levels of digestive enzymes produced in the acinar cells of the pancreas. Normal levels of elastase are above 200 mcg/g and moderate pancreatic insufficiency is between 100-200 mcg/g. This is commonly performed in patients by day 3 in infants and by 2 weeks of age in those born less than 28 weeks gestation (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.).

The elastase test is performed because it is a versatile enzyme that breaks down or hydrolyses the elastin protein in the small intestine to help absorb nutrients and provide elasticity to connective tissues in the lungs, skin, and blood vessels. Pancreatic and neutrophil elastin have a role in digestion, inducing inflammation immune response, and tissue remodeling of the extracellular matrix which is essential in tissue repair, development, and immune responses. High neutrophil elastin is found in respiratory conditions where it degrades the lung, especially the lining of the alveoli where gas exchange takes place. Examples of respiratory conditions are emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This suggests the activity of elastase must be regulated to prevent tissue damage.

The nasal potential difference is done in patients over 8-10 years in indeterminate cases under general anaesthesia for bronchoscopy. Patients are detected if there are abnormal growths called polyps in the nose or if previous surgery on the nose was performed. It should not be done if the patient has had a cold within the last two weeks (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, n.d.). These diagnostic techniques are relevant in cancer diagnosis to determine whether the cancer is related to CF and confirm the CFTR mutation. This will guide clinical practice.

The formation of CF-induced bowel cancers

Patients with CF are at risk of a plethora of different cancers, however, the focus of this article is to enlighten our readers about new risk factors of bowel cancer as part of April Cancer Awareness Month. Patients with CF are six-fold more likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer (Maisonneuve and Lowenfels, 2022). Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) is a rare but aggressive form of bowel cancer that can also occur in CF patients (Parisi et al., 2023). Several mechanisms have been implicated in CF-related cancers.

One of the hallmarks of cancer is chronic inflammatory response. Dysfunction of the CFTR protein can impair ion transport in the intestinal epithelium and increase the expression of cytokines, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This promotes the development of colorectal cancer (Federico et al., 2007).

Inflammation also stimulates dysbiosis in some CF patients. Low levels of good bacteria and high levels of pathogenic bacteria. Examples of beneficial bacteria are Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, whereas, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Enterobacteriaceae can cause harmful infections (Gilbert et al., 2023). Alterations in the microbial composition upregulate the inflammatory mediators that impair the intestinal barrier function and immune surveillance increasing colorectal cancer development (Amaral, Quaresma, and Pankonien, 2020).

The impairment of the CFTR protein can accumulate reactive oxygen species (ROS). This stimulates oxidative stress causing DNA damage and double-strand breaks increasing its ability to invade and metastasize (Zhu et al., 2021).

There are several CF-associated genetic mutations that have been implicated in large and small bowel cancer. The normal function of the tumour suppressor genes, TP53, APC, and SMAD4 can be affected by the CFTR dysfunction in small bowel cancer. TNF-α gene polymorphism was susceptible in CF patients which increased the risk of large bowel cancer (Mandal et al., 2019). As a consequence, cancer cells suppress apoptotic mechanisms and increase inflammation, DNA repair, and cellular proliferation in the bowel (Than et al., 2016). Further research is required to understand the molecular interactions between CFTR and mutated genes.

Conclusion

Overall, there are several new risk factors for bowel cancer, dysbiosis, CF mutation, and the overuse of antibiotics. An imbalance in the gut microbiome can trigger the invasive potential of cancer cells by modulating the immune system to maintain tumour progression. In cases of genetic analysis, one classification system cannot be applied to detect CFTR mutations but improved communication is needed from patient to healthcare professionals and researchers and the media itself (Marson, Bertuzzo, and Ribero, 2016). Current guidelines recommend bowel cancer surveillance for CF patients from the age of 40 or 10 years before the youngest is affected by the relative’s diagnosis by performing colonoscopies periodically to detect precancerous polyps or early stages. Medical attention is needed for unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding or a change in bowel habits. It is important to note that the epidemiologic data for emerging cancers in CF are limited, and further research is necessary to improve our understanding of the prevalence and molecular mechanisms involved. Advancements in research will contribute to improved screening, prevention, and management strategies for cancer in patients with CF. There have been several attempts to target the CFTR gene mutation where long-term clinical trials are needed to elucidate the mechanism of Highly Effective CFTR Modulator Therapy (HEMT) and whether it increases the overall risk of cancer in CF patients.

References

Abedizadeh, R. Majidi, F., Hamid Reza Khorasani, Abedi, H. and Davood Sabour (2023). Colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of carcinogenesis, diagnosis, and novel strategies for classified treatments. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 43(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-023-10158-3.

Adkison, L.R. (2012). Modern Molecular Medicine. Elsevier’s Integrated Review Genetics, pp.217–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-07448-3.00013-3.

Amaral, M.D., Quaresma, M.C. and Pankonien, I. (2020). What Role Does CFTR Play in Development, Differentiation, Regeneration and Cancer? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 21(9), p.3133. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093133.

Appelt, D., Fuchs, T., Steinkamp, G. and Ellemunter, H. (2022). Malignancies in patients with cystic fibrosis: a case series. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 16(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03234-1.

Casjens, S.R. and Hendrix, R.W. (2015). Bacteriophage lambda: Early pioneer and still relevant. Virology, 479-480, pp.310–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.010.

Chauhan, T. (2019a) What Is A Point Mutation?. Available at: https://geneticeducation.co.in/what-is-a-point-mutation/ (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Chauhan, T. (2019b) Real-time PCR: Principle, Procedure, Advantages, Limitations and Applications. Available at: https://geneticeducation.co.in/real-time-pcr-principle-procedure-advantages-limitations-and-applications/#google_vignette (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Chen, Z., Gao, S., Wang, D., Song, D. and Feng, Y. (2016). Colorectal cancer cells are resistant to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody through adapted autophagy American Journal of Translational Research, 8(2), pp.1190–6.

Costa, T.R.D., Felisberto-Rodrigues, C., Meir, A., Prevost, M.S., Redzej, A., Trokter, M. and Waksman, G. (2015). Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nature Reviews Microbiology, [online] 13(6), pp.343–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3456.

Crowe-McAuliffe, C. and Wilson, D.N. (2022). Putting the antibiotics chloramphenicol and linezolid into context. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, [online] 29(2), pp.79–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00725-7.

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2023). Types of CFTR Mutations. Available at: https://www.cff.org/research-clinical-trials/types-cftr-mutations. (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Cystic Fibrosis Medicine & Cystic Fibrosis Online (2021) The Genetics of Cystic Fibrosis Available at: https://cysticfibrosis.online/genetics/ (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

De Boeck, K. and Amaral, M.D. (2016). Progress in therapies for cystic fibrosis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, [online] 4(8), pp.662–674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(16)00023-0.

Dimitrakopoulou, D., Rethemiotaki, I., Frontistis, Z., Xekoukoulotakis, N.P., Venieri, D. and Mantzavinos, D. (2012). Degradation, mineralization and antibiotic inactivation of amoxicillin by UV-A/TiO2 photocatalysis. Journal of Environmental Management, [online] 98, pp.168–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.01.010.

Dousa, K.M., Nguyen, D.C., Kurz, S.G., Taracila, M.A., Bethel, C.R., Schinabeck, W., Kreiswirth, B.N., Brown, S.T., Boom, W.H., Hotchkiss, R.S., Remy, K.E., Jacono, F.J., Daley, C.L., Holland, S.M., Miller, A.A. and Bonomo, R.A. (2022). Inhibiting Mycobacterium abscessus Cell Wall Synthesis: Using a Novel Diazabicyclooctane β-Lactamase Inhibitor To Augment β-Lactam Action. mBio, 13(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.03529-21.

Elliott, S.J., Sperandio, V., GirónJ.A., Shin, S., Mellies, J.L., Wainwright, L., Hutcheson, S.W., McDaniel, T.K. and Kaper, J.B. (2000). The Locus of Enterocyte Effacement (LEE)-Encoded Regulator Controls Expression of Both LEE- and Non-LEE-Encoded Virulence Factors in Enteropathogenic and Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infection and Immunity, 68(11), pp.6115–6126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.68.11.6115-6126.2000.

Elsaghir, H. and Reddivari, A.K.R. (2020). Bacteroides Fragilis. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31971708/ (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Elsalem, L., Jum’ah, A.A., Alfaqih, M.A. and Aloudat, O. (2020). The Bacterial Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology, Volume 13, pp.151–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/ceg.s243337.

Falzano, L., Filippini, P., Travaglione, S., Miraglia, A.G., Fabbri, A. and Fiorentini, C. (2006). Escherichia coli Cytotoxic Necrotizing Factor 1 Blocks Cell Cycle G 2 /M Transition in Uroepithelial Cells. Infection and Immunity, 74(7), pp.3765–3772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.01413-05.

Federico, A., Morgillo, F., Tuccillo, C., Ciardiello, F. and Loguercio, C. (2007). Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in human carcinogenesis. International Journal of Cancer, 121(11), pp.2381–2386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23192.

Figueredo Lago, J.E., Armas Cayarga, A., González González, Y.J. and Collazo Mesa, T. (2017). A simple, fast and inexpensive method for mutation scanning of CFTR gene. BMC Medical Genetics, [online] 18(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-017-0420-9.

Figueredo-Lago, J.E., Armas-Cayarga, A., González González, Y.J., Collazo-Mesa, T., Garcia de la Rosa, I., Perea-Hernández, Y., and Santos-González, E.N (2015) Development of a method to detect three frequent mutations in the CFTR gene using allele-specific real time PCR Biotecnologia Aplicada, 32(4), pp.4301-4306

Gilbert, B., Kaiko, G., Smith, S. and Wark, P. (2023). A systematic review of the colorectal microbiome in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, [online] 25(5), pp.843–852. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16472.

Gonzalez-Gutierrez, L., Motiño, O., Barriuso, D., Juan, Alvarez-Frutos, L., Kroemer, G., Palacios-Ramirez, R. and Senovilla, L. (2024). Obesity-Associated Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 25(16), pp.8836–8836. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25168836.

Graillot, V., Dormoy, I., Dupuy, J., Shay, J.W., Huc, L., Mirey, G. and Vignard, J. (2016). Genotoxicity of Cytolethal Distending Toxin (CDT) on Isogenic Human Colorectal Cell Lines: Potential Promoting Effects for Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, [online] 6. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2016.00034.

Hajishengallis, G., Darveau, R.P. and Curtis, M.A. (2012). The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10(10), pp.717–725. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2873.

Hernández-Luna, M.A., López-Briones, S. and Luria-Pérez, R. (2019). The Four Horsemen in Colon Cancer. Journal of Oncology, 2019, pp.1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5636272.

Hsu, Y., Jubelin, G., Frédéric Taieb, Jean-Philippe Nougayrède, Oswald, E. and Stebbins, C.E. (2008). Structure of the Cyclomodulin Cif from Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 384(2), pp.465–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.051.

Jiang, Q., Feng, M., Ye, C. and Yu, X. (2022). Effects and relevant mechanisms of non-antibiotic factors on the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in water environments: A review. Science of The Total Environment, 806, p.150568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150568.

Jinadasa, R.N., Bloom, S.E., Weiss, R.S. and Duhamel, G.E. (2011). Cytolethal distending toxin: a conserved bacterial genotoxin that blocks cell cycle progression, leading to apoptosis of a broad range of mammalian cell lineages. Microbiology, [online] 157(7), pp.1851–1875. doi:https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.049536-0.

Kerem, B., Rommens, J.M., Buchanan, J.A., Markiewicz, D., Cox, T.K., Chakravarti, A., Buchwald, M. and Tsui, L.C. (1989). Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science (New York, N.Y.), 245(4922), pp.1073–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2570460.

Kümmerer, K. (2009). Antibiotics in the aquatic environment – A review – Part I. Chemosphere, 75(4), pp.417–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.006.

Li, B., Garstka, M. and Li, Z.-F. (2020). Chemokines and their receptors promoting the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells into the tumor. Molecular Immunology, 117, pp.201–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2019.11.014.

LibreTexts (n.d) 15.13: Amides- Structures and Names Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Chemistry/The_Basics_of_General_Organic_and_Biological_Chemistry_(Ball_et_al.)/15%3A_Organic_Acids_and_Bases_and_Some_of_Their_Derivatives/15.13%3A_Amides-_Structures_and_Names (Accessed: 20th June 2025.

Liu, Y.-C., Tang, X.-Y., Lang, J.-X., Qiu, Y., Chen, Y., Li, X.-Y., Cao, Y. and Zhang, C.-D. (2025). Effects of antibiotic exposure on risks of colorectal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Translational Medicine, 23(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06727-5.

Lu, Y.C., Chen, H., Fok, K.L., Tsang, L.L., Yu, M.K., Zhang, X.H., Chen, J., Jiang, X., Chung, Y.W., Chun, A., Hung, Y., Huang, H.F. and Chan, H.C. (2012). CFTR mediates bicarbonate-dependent activation of miR-125b in preimplantation embryo development. Cell Research, 22(10), pp.1453–1466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2012.88.

Maisonneuve, P. and Lowenfels, A.B. (2022). Cancer in Cystic Fibrosis: A Narrative Review of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Screening, and Treatment Challenges. Chest, 161(2), pp.356–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.09.003.

Mandal, R., Khan, M., Hussain, A., Akhter, N., Jawed, A., Dar, S., Wahid, M., Panda, A., Mohtashim Lohani, Mishra, B.N. and Haque, S. (2018). A trial sequential meta-analysis of TNF-α –308G>A (rs800629) gene polymorphism and susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Bioscience Reports, 39(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1042/bsr20181052.

Marson, F.A.L., Bertuzzo, C.S. and Ribeiro, J.D. (2016). Classification of CFTR mutation classes. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, [online] 4(8), pp.e37–e38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(16)30188-6.

McClean, P. (1997) PCR Analysis of the Cystic Fibrosis Gene Available at: https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/~mcclean/plsc431/markers/marker2.htm (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Mima, K., Cao, Y., Chan, A.T., Qian, Z.R., Nowak, J.A., Masugi, Y., Shi, Y., Song, M., da Silva, A., Gu, M., Li, W., Hamada, T., Kosumi, K., Hanyuda, A., Liu, L., Kostic, A.D., Giannakis, M., Bullman, S., Brennan, C.A. and Milner, D.A. (2016). Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Carcinoma Tissue According to Tumor Location. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 7(11), p.e200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2016.53.

Murphy, S.V. and Ribeiro, C.M.P. (2019). Cystic Fibrosis Inflammation: Hyperinflammatory, Hypoinflammatory, or Both? American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 61(3), pp.273–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2019-0107ed.

Nelson, B. and Wiles, A. (2022). A growing link between antibiotics and colon cancer. Cancer Cytopathology, 130(5), pp.318–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22582.

Nguyen, L.H., Cao, Y., Nurgul Batyrbekova, Bjorn Roelstraete, Ma, W., Khalili, H., Song, M., Chan, A.T. and Ludvigsson, J.F. (2022). Antibiotic Therapy and Risk of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: A National Case-Control Study. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 13(1), pp.e00437–e00437. doi:https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000437.

Nougayrède, J.-P., Taieb, F., Rycke, J.D. and Oswald, E. (2005). Cyclomodulins: bacterial effectors that modulate the eukaryotic cell cycle. Trends in Microbiology, 13(3), pp.103–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2005.01.002.

Petrelli, F., Ghidini, M., Ghidini, A., Perego, G., Cabiddu, M., Khakoo, S., Oggionni, E., Abeni, C., Hahne, J.C., Tomasello, G. and Zaniboni, A. (2019). Use of Antibiotics and Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cancers, [online] 11(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081174.

Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C., Puschhof, J., Huber, A.R., van Hoeck, A., Wood, H.M., Nomburg, J., Gurjao, C., Manders, F., Dalmasso, G., Stege, P.B., Paganelli, F.L., Geurts, M.H., Beumer, J., Mizutani, T., Miao, Y., van der Linden, R., van Elst, S., Garcia, K.C., Top, J. and Willems, R.J.L. (2020). Mutational Signature in Colorectal Cancer Caused by Genotoxic Pks + E. Coli. Nature, [online] 580, pp.1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2080-8.

Richards, C.S., Bradley, L.A., Amos, J., Allitto, B., Grody, W.W., Maddalena, A., McGinnis, M.J., Prior, T.W., Popovich, B.W. and Watson, M.S. (2002). Standards and Guidelines for CFTR Mutation Testing. Genetics in Medicine, 4(5), pp.379–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00125817-200209000-00010.

Riordan, J., Rommens, J., Kerem, B., Alon, N., Rozmahel, R., Grzelczak, Z., Zielenski, J., Lok, S., Plavsic, N., Chou, J. and et, al. (1989). Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science, 245(4922), pp.1066–1073. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2475911.

Rommens, J.M., Iannuzzi, M.C., Kerem, B., Drumm, M.L., Melmer, G., Dean, M., Rozmahel, R., Cole, J.L., Kennedy, D. and Hidaka, N. (1989). Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science (New York, N.Y.), [online] 245(4922), pp.1059–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2772657.

Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (n.d.) Making the diagnosis Available at: https://www.rbht.nhs.uk/sites/nhs/files/Cystic%20fibrosis%20guidelines/CF%20G%202020/5.pdf (Accessed: 22nd June 2025)

Schmidt, G., Sehr, P., Wilm, M., Selzer, J., Mann, M. and Aktories, K. (1997). Gln 63 of Rho is deamidated by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1. Nature, 387(6634), pp.725–729. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/42735.

Sears, C.L., Islam, S., Saha, A., Arjumand, M., Alam, N., Faruque, A. S. G., Salam, M. A., Shin, J., Hecht, D., Weintraub, A., Sack, R. Bradley and Qadri, F. (2008). Association of EnterotoxigenicBacteroides fragilisInfection with Inflammatory Diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 47(6), pp.797–803. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/591130.

Smyth, A.R., Bell, S.C., Bojcin, S., Bryon, M., Duff, A., Flume, P., Kashirskaya, N., Munck, A., Ratjen, F., Schwarzenberg, S.J., Sermet-Gaudelus, I., Southern, K.W., Taccetti, G., Ullrich, G. and Wolfe, S. (2014). European Cystic Fibrosis Society Standards of Care: Best Practice guidelines. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 13(1), pp.S23–S42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2014.03.010.

Sun, J. (2022). Impact of bacterial infection and intestinal microbiome on colorectal cancer development. Chinese Medical Journal, 135(4), pp.400–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000001979.

Tamashiro, J. (2023) Chaperone Proteins | Definition & Functions. Available at: https://study.com/learn/lesson/chaperone-proteins-function-purpose.html (Accessed: 24th June 2025)

Tankeshwar, A. (2025) Real-time PCR: Principles and Applications. Available at: https://microbeonline.com/real-time-pcr-principles-and-applications/ (Accessed: 22ND June 2025)

Than, B.L.N., Linnekamp, J.F., Starr, T.K., Largaespada, D.A., Rod, A., Zhang, Y., Bruner, V., Abrahante, J., Schumann, A., Luczak, T., Walter, J., Niemczyk, A., O’Sullivan, M.G., Medema, J.P., Fijneman, R.J.A., Meijer, G.A., Van den Broek, E., Hodges, C.A., Scott, P.M. and Vermeulen, L. (2016). CFTR is a tumor suppressor gene in murine and human intestinal cancer. Oncogene, [online] 35(32), pp.4179–4187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2015.483.

Waglechner, N. and Wright, G.D. (2017). Antibiotic resistance: it’s bad, but why isn’t it worse? BMC Biology, 15(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0423-1.

Wainwright, B.J., Scambler, P.J., Schmidtke, J., Watson, E.A., Law, H.-Y., Farrall, M., Cooke, H.J., Eiberg, H. and Williamson, R. (1985). Localization of cystic fibrosis locus to human chromosome 7cen–q22. Nature, [online] 318(6044), pp.384–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/318384a0.

Wang, J.-L., Chang, C.-H., Lin, J.-W., Wu, L.-C., Chuang, L.-M. and Lai, M.-S. (2014). Infection, antibiotic therapy and risk of colorectal cancer: A nationwide nested case-control study in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Cancer, 135(4), pp.956–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28738.

Wassenaar, T.M. (2018). E. coli and colorectal cancer: a complex relationship that deserves a critical mindset. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 44(5), pp.619–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841x.2018.1481013.

Yusuf, K., Sampath, V. and Umar, S. (2023). Bacterial Infections and Cancer: Exploring This Association And Its Implications for Cancer Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), pp.3110–3110. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043110.

Zhang, J., Haines, C., Watson, A.J.M., Hart, A.R., Platt, M.J., Pardoll, D.M., Cosgrove, S.E., Gebo, K.A. and Sears, C.L. (2019). Oral antibiotic use and risk of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom, 1989–2012: a matched case–control study. Gut, [online] 68(11), pp.1971–1978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318593.

Zhu, G.-X., Gao, D., Shao, Z.-Z., Chen, L., Ding, W.-J. and Yu, Q.-F. (2021). Wnt/β-catenin signaling: Causes and treatment targets of drug resistance in colorectal cancer. Molecular Medicine Reports, [online] 23(2), p.105. doi:https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2020.11744.

Leave a comment