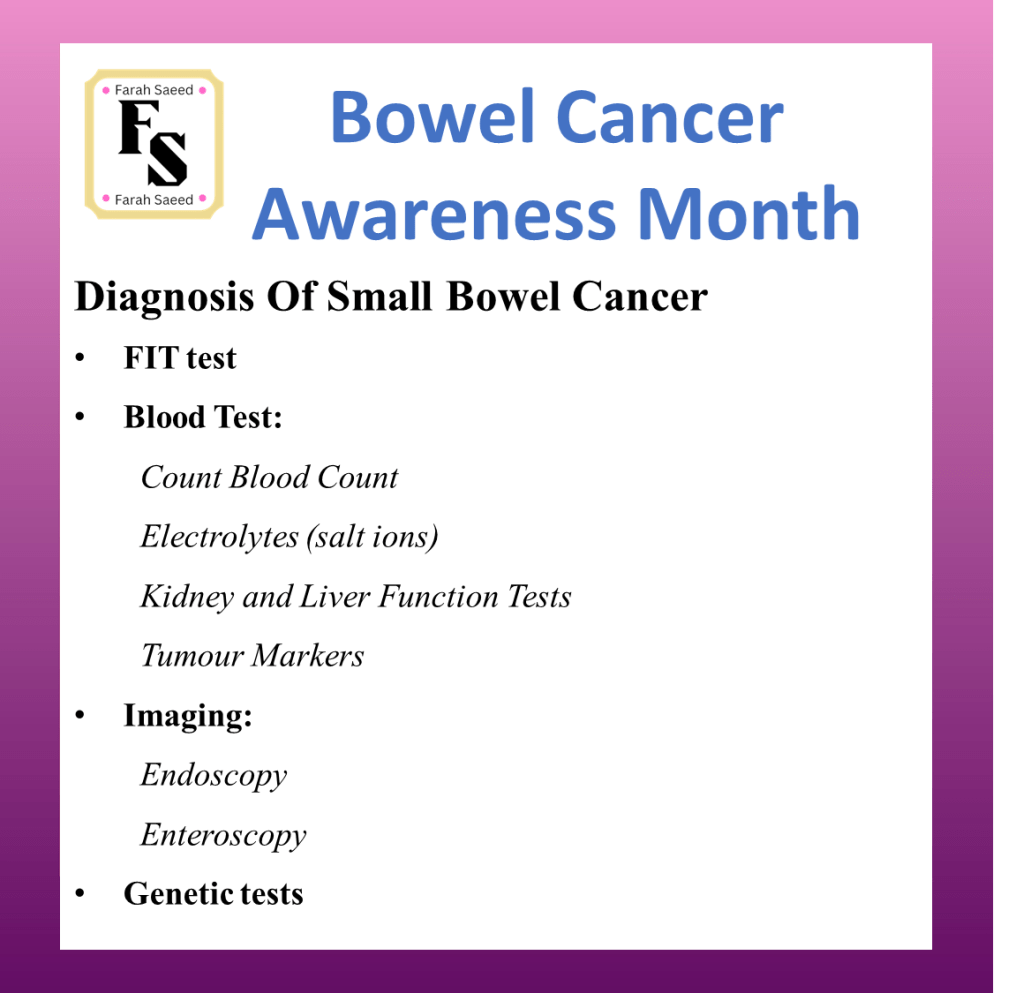

Diagnosis Of Small Bowel Cancer

During the consultation with the doctor, there will be an initial discussion of the patient’s symptoms and how long they have experienced them. Questions will also be asked about their lifestyle and family history. The doctor will conduct physical examination and the relevant further tests to detect cause.

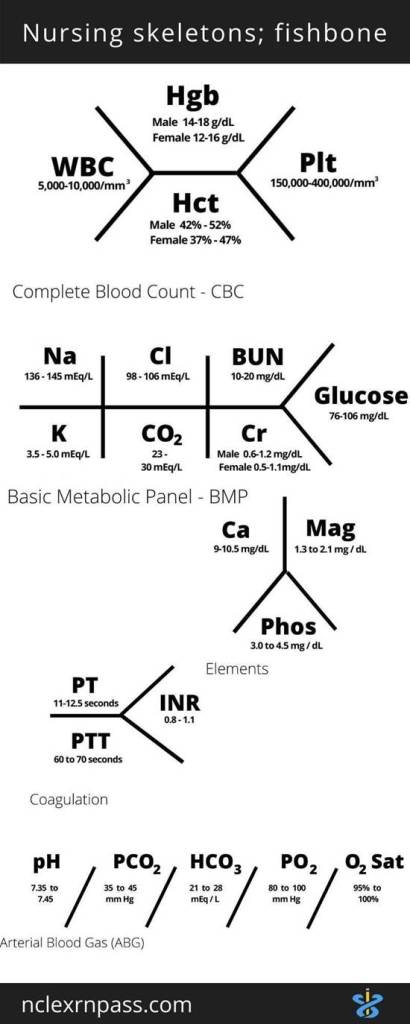

What is Haemogram/Complete Blood Count? Video Support

Types Of Blood Tests

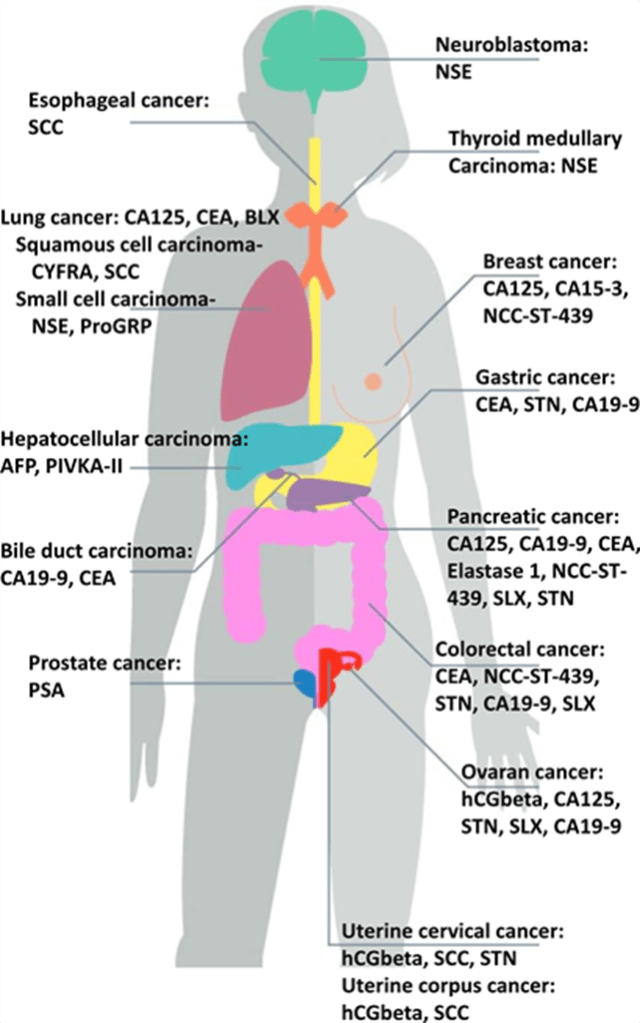

Tumour Markers

Tumour markers like serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be elevated but cannot be used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. (Khosla et al., 2022)

CA 19-9 is elevated in cancers associated with the stomach, bowel, pancreatic, liver and gallbladder (Mangla, 2023).

Types of Tumour Markers (Creative Commons, 2025)

Are there any other screening test besides FIT?

No official screening test for small bowel cancer which is why it is commonly detected in the later stage where it is 7 and 8 months from symptoms (Ceresi et al., 1995). There appears obstruction in the intestines (22-26%) and perforation (6-9%).

Why Does Late Diagnosis Commonly Occur in Patients With Small Bowel Cancer?

Reason One: Obstruction of the bowel

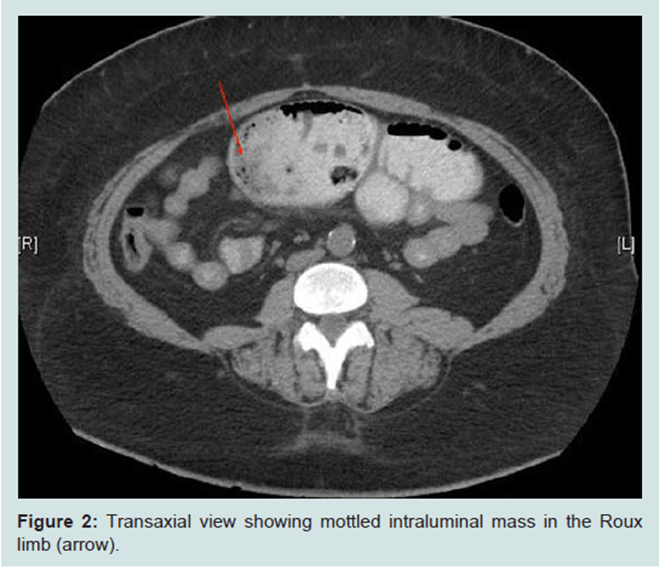

Obstruction may occur because of the narrowing of the lumen where ‘apple core’ lesion may appear and possible large intraluminal mass until advanced. This cause difficulty to understand the difference between benign (early stage) and malignant (late stage) cancers (Khosla et al., 2022)

(Creative Commons, 2025)

(Creative Commons, 2025)

Reason Two: Overlapping symptoms with blood conditions

Symptoms may overlap with iron deficiency anaemia causing negative findings on colonoscopy and standard oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Reason Three: The length of the small bowel

It can also be due to the length which can be difficult for scoping techniques.

Imaging Techniques

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

It is an endoscopy where a thin flexible tube and small camera and light can examine the upper gastro intestinal tract (oesophagus (food pipe), stomach and duodenum).

Theresa Oey EGD

CT scan

A CT scan of the small bowel – This can be difficult because it is in the middle area of the digestive tract.

Other imaging techniques

Several methods can enhance the amount of intestinal surface area that can be visualized beyond EGD or colonoscopy with terminal ileal examination, including push enteroscopy, video capsule endoscopy (VCE), and deep small bowel enteroscopy (ie, balloon enteroscopy and spiral enteroscopy).

Balloon enteroscopy

Video capsule endoscopy

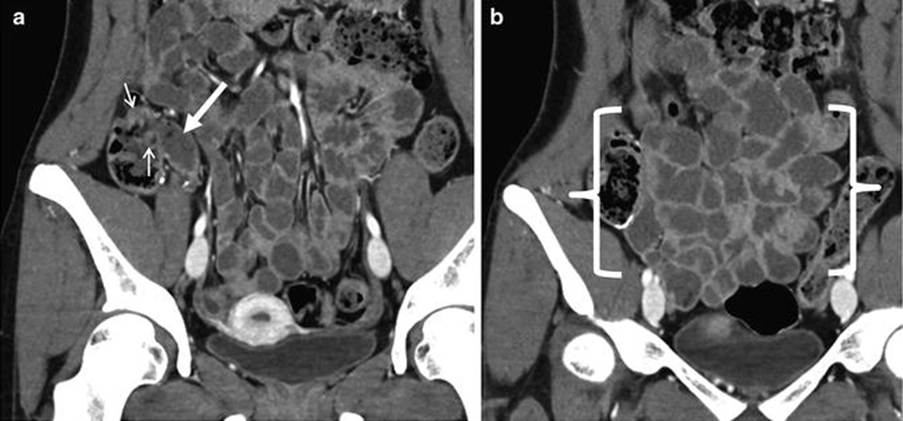

Other techniques to detect small bowel lesions and abnormalities in the wall with contrast where Oral contrast media 1.5-2 litres over 45-60 minutes with entering CT 45 seconds (Khosla et al., 2022)

It can be done via the oral or anal. Accuracy is 80%.

CT enterocylsis

Non-invasive method It helps to improve sensitivity by 93% and specificity 99%. It is performed with nasogastric infusion (Khosla et al., 2022)

Useful to investigate Crohn’s disease, small bowel obstruction and unexplained bleeding.

Enterography

Cross-sectional enterography Sensitivity 76%. Specificity 95%

MR enterography Sensitivity 93%, Specificity 99% (Khosla et al., 2022)

Coronal CT enterography images of the small bowel. The terminal ileum is presented at the white arrow. The small arrow indicates the ileocecal valve which is the haustral fold of the caecum (first segment of the large intestine. The distal ileum is between the brackets. There is thin walls and decreased mural enhancement which indicates inflammation or altered perfusion (Abdominal Key, 2017)

Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT)

This type of imaging test helps with staging of cancer and monitor response to treatment. (Khosla et al., 2022)

CT findings differ and depend on contrast agent.

Carcinomas of the duodenum: They are characterised with Polypoidal (resembles polyps) and delineated lesions (clear boundaries).

Carcinomas of the jejunum and ileum: They are characterised with annular narrowing (ring-shaped narrowing), abrupt concentric (circles with the similar centre), irregular overhanging stenosis which lead to partial or complete obstruction. Stenosis and stricture refer that the lumen of the intestine is narrow. (Khosla et al., 2022).

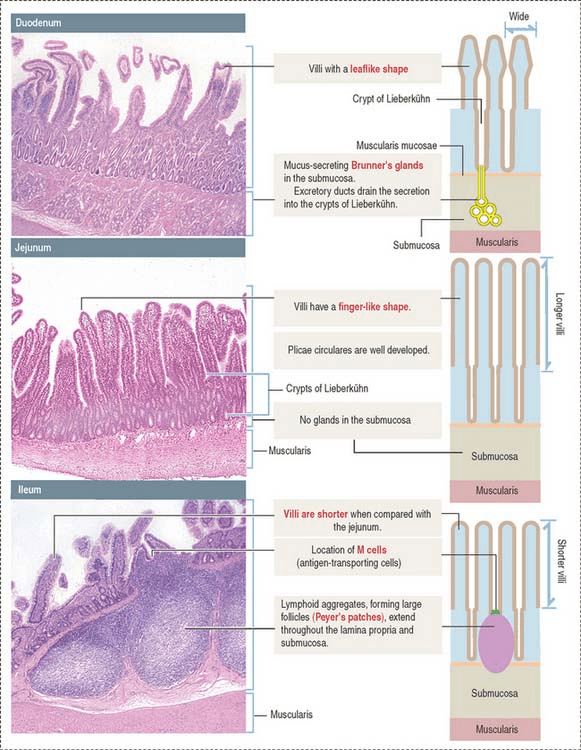

Histological appearance under the microscope

The cells and tissue of the small intestine can be analysed using a microscope. The normal histology is presented below. The cells and tissue of the three main segments of the small intestine, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum can be analyzed using a microscope. They have distinctive features and the normal histology presented below was performed using a light microscope. A light microscope is an instrument that uses visible light and lenses (eyepiece and objective) to observe small objects with magnification of up to 1000 times.

The layers of the small intestine are mucosa, muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and muscularis. In the lining of the mucosa, there are finger-like projections of villi that function in absorption. They form deep crypts in the mucosa. However, they vary in their structural appearance throughout the small intestine. For instance, in the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine extends from the pylorus of the stomach and is surrounded by an incomplete serosa and an extensive adventitia. The villi have a broad and short leaf-like shape, whereas, in the jejunum, they become longer and finger-like appearance with a well-developed lacteal in the core of the villus. The lacteal contains lymph vessels that facilitate the immune system and also help in absorbing small fatty acids and glycerol. In the ileum, the villi appear much shorter. This suggests that the length of the villi depends on two main factors: The distention (enlarged or stretched) of the intestinal wall and the contraction of the smooth muscle fibers in the villus core (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

The crypts of Lieberkühn otherwise known as the intestinal glands reside in the invaginations of the mucosa and are found between adjacent villi. Invaginations are tissue foldings to form a tube or pouch structure on the surface. They are simple tubular glands that further help increase the surface area to absorb the nutrients that have been digested in the small intestine. Digestion in the small intestine is facilitated by enzymes secreted by the pancreas and is released into the duodenum via the pancreatic duct. Bile that performs non-enzymatic digestion of fats from large fat droplets to small fat droplets is transported from the gall bladder to the duodenum via the common bile duct. The sphincter of Oddi is present at the terminal ampullary portion between both ducts. An increase in the total surface of the mucosa reflects the absorptive function of the small intestine (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

The base of the crypts of Lieberkühn may contain Paneth cells in the duodenum. In the jejunum and ileum, Paneth cells are found at the base of the crypts of Lieberkühn. They contribute antimicrobial peptides (small proteins) such as defensins that help control the resident and pathogenic microbial flora. (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

The muscular mucosa is the boundary between the mucosa and submucosa. (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

The submucosa layer varies in its contents and structure throughout the small intestine. In the duodenum, there are Brunner’s glands present in the submucosa. They have a tubular appearance (tubuloacinar) that secrete mucus. The presence of excretory ducts drains the mucus secretions into the crypts of Lieberkühn. The mucus secretion has an alkaline pH between 8.8 to 9.3. This helps to neutralize the acidic chyme coming from the stomach (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

On the other hand, there are no glands present in the submucosa of the jejunum and ileum. The submucosa of the ileum contains large follicles called Peyer’s patches. Peyer’s patches extend in the lamina propria in the crypts of the mucosa and form part of the submucosa. Antigen-transporting M cells present in the lumen of the small intestine. Peyer’s patches and M cells are among the immune surveillance that prevent pathogenic destruction of the intestinal tissue. In the jejunum, there may be Peyer’s patches in the lamina propria but not predominantly. Peyer’s patches are a characteristic feature of the ileum (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

The muscularis consists of two types of smooth muscle: the inner layer performs circular movement whereas the outer layer entails longitudinal muscle. Generally, muscles facilitate movement, support, and contraction, in this case, the movement of food contents within the small intestine. Segmentation is the uncoordinated movement of mixing and mobilizing food into segments. Peristalsis is a coordinated movement where food contents are propelled in a proximal (orad) contraction and then distal relaxation (orad) sequentially. It also serves as an immune defense mechanism to prevent bacterial colonization (Basic Medical Key, 2016).

Histological images of the different segments of the small bowel (Basic Medical Key, 2016)

Genetic analysis

Schrock et al. (2017) examined genetic changes using a 236 or 315 cancer gene panel to distinguish between bowel cancer from gastric cancer. There were 317 samples from small bowel cancer and 889 samples from gastric cancer and 6353 samples from colon cancer. There were 12 different expression of genes between small bowel and large bowel cancer where the expressions below presents the most significant difference.

| Name of gene | Percentage gene expression in Small bowel cancer (%) | Percentage gene expression in Large bowel cancer (%) | P-value |

| APC | 26.8 | 75.9 | P < 0.001 |

| TP53 | 58.4 | 75 | P < 0.001 |

| CDKN2A | 14.5 | 2.6 | P < 0.001 |

There were 12 different expression of genes between small bowel and Stomach cancer. The table below presents the most significant difference.

| Name of gene | Percentage gene expression in Small bowel cancer (%) | Percentage gene expression in stomach cancer (%) | P-value |

| KRAS | 53.6 | 14.2 | P < 0.001 |

| APC | 26.8 | 7.8 | P < 0.001 |

| SMAD4 | 17.4 | 5.2 | P < 0.001 |

These results indicate there are differences in expression of mutated genes which influences clinical outcome and may also vary based on the segment within each organ.

References

Abdominal Key (2017) CT Enterography. Available at: https://abdominalkey.com/ct-enterography/ (Accessed: 17th June 2025)

Ciresi, D.L. and Scholten, D.J. (1995). The continuing clinical dilemma of primary tumors of the small intestine. PubMed, 61(8), pp.698–3.

Khosla, D., Dey, T., Madan, R., Gupta, R., Goyal, S., Kumar, N. and Kapoor, R. (2022). Small bowel adenocarcinoma: An overview. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, [online] 14(2), pp.413–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i2.413. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8918997/

Schrock, A.B., Devoe, C., McWilliams, R.R., Sun, J., Aparicio, T., Stephens, P.J., Ross, J.S., Wilson, R.H., Miller, V.A., Ali, S.M. and Overman, M.J. (2017). Genomic Profiling of Small-Bowel Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncology, 3(11), pp.1546–1546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1051.

Updated April 2025 Next Review March 2027