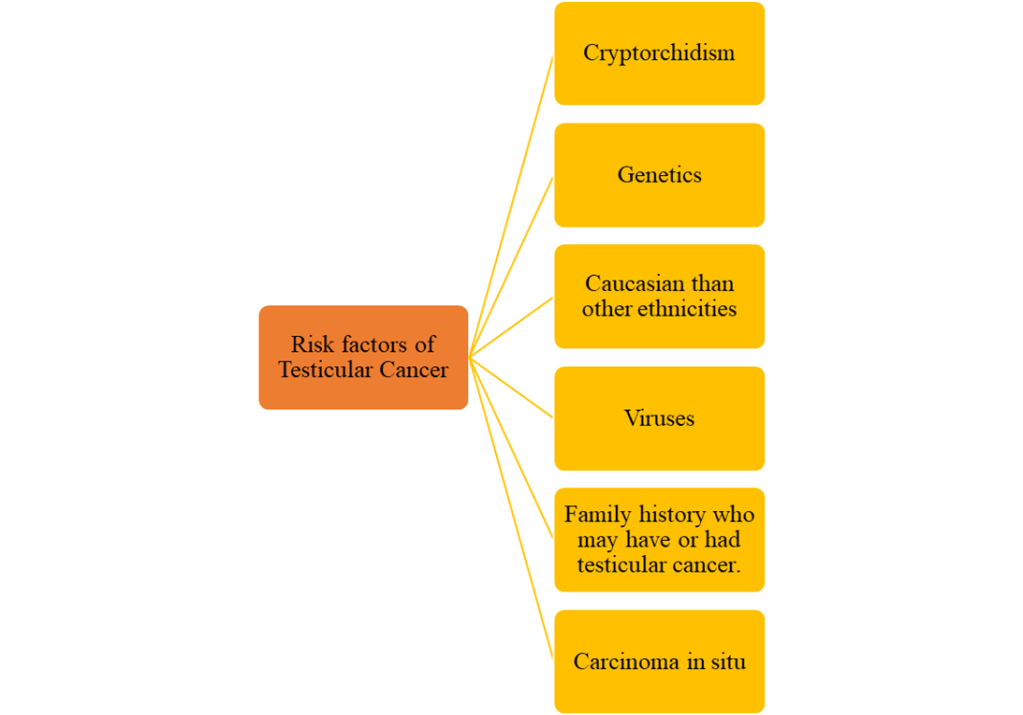

Risk factors of Testicular Cancer

The exact cause of testicular cancer is unknown but there are a range of risk factors that increases incidence of testicular cancer.

(Cancer Research UK, 2025a, 2025b)

Health Conditions

Carcinoma in situ (intratubular germ cell neoplasia)

This is the non-invasive precancerous condition that affect testicular germ cells. They can normally be diagnosed under a biopsy or fertility test. However, under the microscope, cells appear typical because they do not look like they are invasive and require monitoring. Other tests may include screenings, ultrasounds, blood tests to determine whether the tumour is malignant (Roland, 2024). If these abnormal cells are not removed, it increases risk.

Undescended testicle (cryptorchidism)

This is where the testicles fail to descend down when the baby is born or within the first year. It remains in the stomach (Swerdlow, Higgins and Pike, 1997)

It is a risk factor for testicular cancer where there is two to four fold increase risk

It is more common in the cancers of the right testis (Ferguson and Agoulnik, 2013; Leslie, Sajjad and Villanueva, 2024)

It is not a risk factor for spermocytic tumour (Secondino et al., 2023).

No association with hormonal changes of the testosterone or oestrogen.

No association with Gynaecomastia (enlarged breasts in males) (Secondino et al., 2023).

Testicular trauma (Coupland et al., 1999; Haughey et al., 1989)

High maternal oestrogen level (Depue, Pike and Henderson, 1983)

Kleinfelter’s syndrome

A genetic condition caused by a male born with an extra chromosome

e.g. XXY chromosome rather than XY chromosome.

Amongst the characteristics are infertility, osteoporosis, learning difficulties, breast cancer and gynaecomastia (enlarged breast) (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Genetics and Familial factors

Family history where a relative may have or had testicular cancer has an increased risk of six to ten-fold testicular cancer (Del Risco Kollerud, 2019; Hemminki and Chen, 2006).

Testicular cancers are highly aneuploid (abnormal chromosome number) De Vries et al. (2020).

Duplication or deletion of the short arm of chromosome 12 increases the risk of GCNIS tumours (Secondino et al., 2023).

Mutations of the p53 tumour suppressor gene have been observed in 66% of GCNIS tumours (Kuczyk et al., 1996; Bosl and Motzer, 1997).

Genetic polymorphism of the PTEN tumour suppressor gene increases the risk (Andreassen et al., 2013).

The presence of AFP mRNA suggests an overlap between seminoma and embryonal carcinoma (Looijenga et al., 2007).

Single nucleotide polymorphism (a single nucleotide change) (SNP) like 15q21.3 increases the incidence of testicular cancer.

Markers like M2A, C-KIT, and OCT4/NANOG molecular markers increase the risk of GCNIS tumours (Loveday et al., 2018).

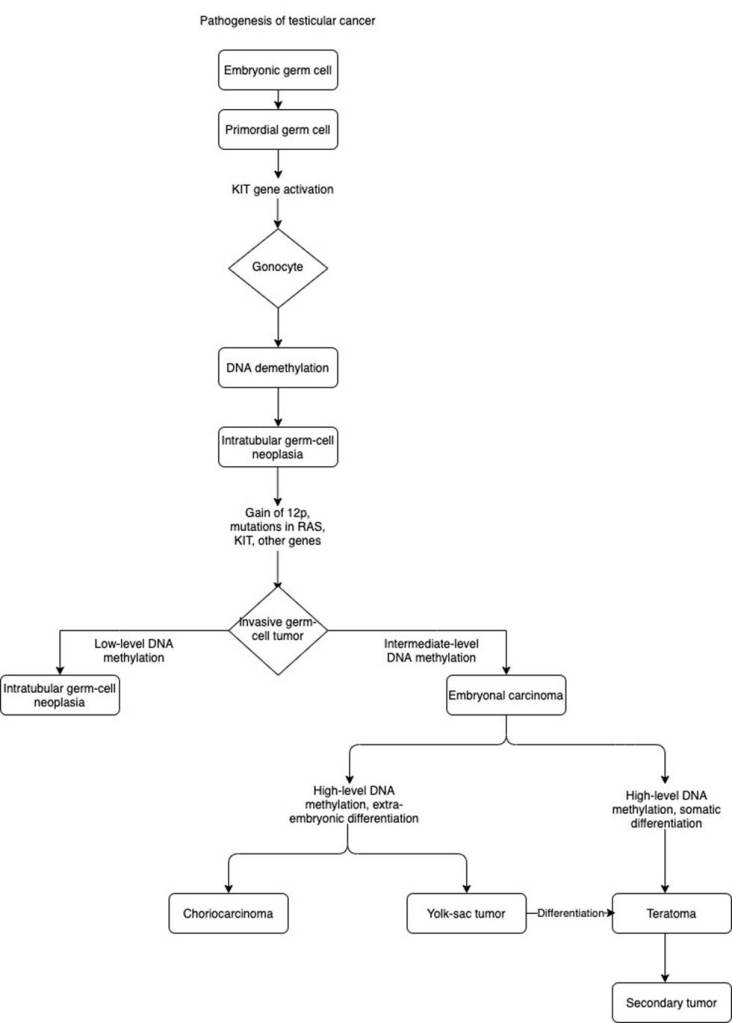

DNA methylation

Gene expression and modifications like DNA methylations can develop into different histological subtypes presented by the flowchart designed by Gaddam, Bicer, and Chesnut (2023). In normal conditions, primordial germ cells to gonocytes require the activation of the KIT gene. The KIT gene encodes for the enzyme, receptor tyrosine kinase. This binds to the stem cell factor and facilitates signal transduction and cellular processes like growth and migration.

DNA methylation is the addition of a methyl group to the 5’ carbon of the cytosine ring to form 5-methylcytosine. This process is catalyzed and maintained by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT). In normal conditions, DNA methylation can lock genes in the off position (inhibit transcription). This is essential for processes like embryonic development, X-chromosome inactivation, and maintaining chromosome stability. DNMT1 functions in established DNA methylation patterns, in contrast, DNMT3a and DNMT3b partake in new DNA methylation patterns (LabClinics, n.d.).

DNA demethylation (removal of the methyl group) by DNA demethylases can lead to precancerous lesions of intratubular germ cell neoplasia. This suggests that DNA methylation is a reversible epigenetic modification and can reprogram genes to induce tumourigenesis. Gain of 12p and mutations in KIT and RAS and other genes can lead to the invasive form of germ cell tumour (Gaddam, Bicer, and Chesnut, 2023). The level of DNA methylation can result in different histological subtypes of testicular cancer. Both DNMT1 and DNMT3b can maintain the level of hypermethylation in cancer cells. Hypomethylation (low-level DNA methylation) exhibits traits of intratubular germ cell neoplasia.

A milder effect of DNA methylation (intermediate level) can cause embryonal carcinoma. Hypermethylation (high-level DNA methylation) can influence two forms of differentiation: embryo and somatic. Hypermethylation with extra-embryonic differentiation causes choriocarcinoma and yolk-sac tumour. Hypermethylation with somatic differentiation can cause teratoma with the potential to form secondary tumours where silencing of tumour suppressor genes involved in the regulation of cell cycles and processes can lead to metastasis (LabClinics, n.d.). In addition, the Yolk-sac tumour can be directly differentiated into teratoma. This highlights the role of DNA mutations and hypermethylation in the formation of non-seminomas by influencing genes involved in tumour cell invasion, DNA repair, and dysregulation of cellular events (LabClinics, n.d.).

Microbiological Factors

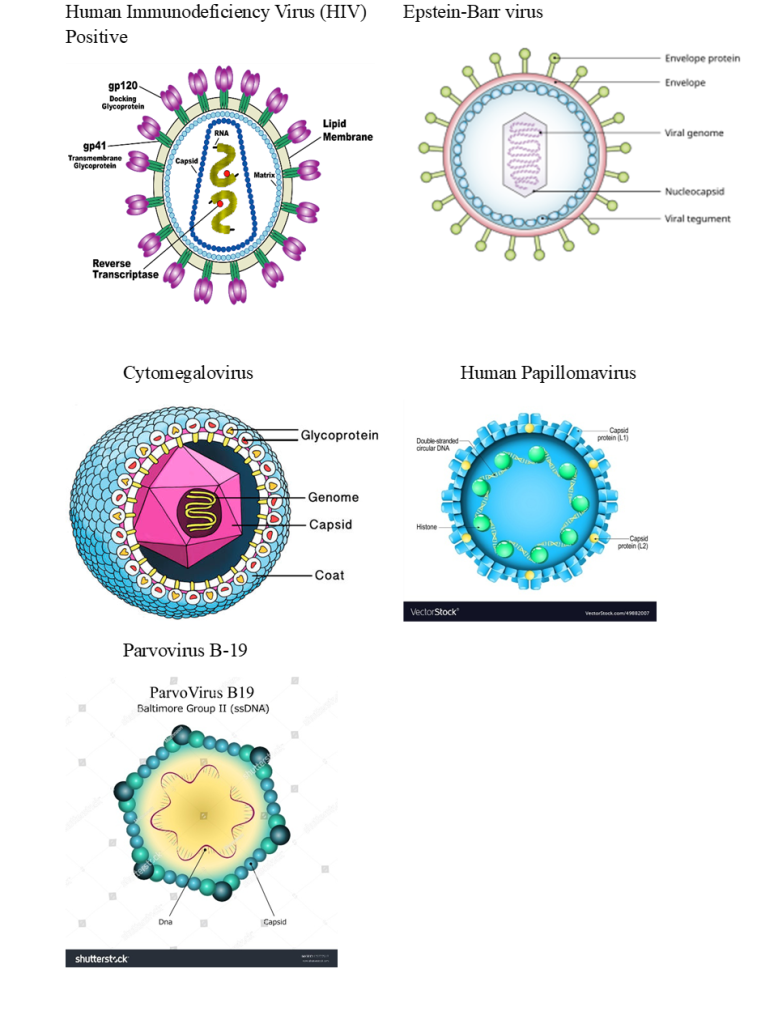

Viruses

A number of viruses involved in testicular pathogenesis (Garolla et al., 2019).

Sociodemographic factors

Ethnicity

It is more common in Caucasian men than Afro-Carribean and Ethnic minorities. The incidence in Western Europe is 8.7 per 100,000 men compared to Northern Europe being 7.2 per 100,000 (Park et al., 2018)

The highest mortality is in West Asia.

The low mortality rate in other continents is due to awareness of testicular cancer, self-examination, and applying various treatment strategies (Park et al., 2018).

Age

Younger men are at risk.

Sex and gender

Males are at risk.

Trans women can also develop testicular cancer if they haven’t had an operation to remove their testicles (orchidectomy).

Height

Taller men than average are at risk.

References

Andreassen, K.E., Kristiansen, W., Karlsson, R., Aschim, E.L., Dahl, O., Fossa, S.D., Adami, H.O., Wiklund, F., Haugen, T.B. and T. Grotmol (2013). Genetic variation in AKT1, PTEN and the 8q24 locus, and the risk of testicular germ cell tumor. Human Reproduction, 28(7), pp.1995–2002. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det127.

Bosl, G.J. and Motzer, R.J. (1997). Testicular Germ-Cell Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(4), pp.242–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199707243370406.

Cancer Research UK (2025a) Types of testicular cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/types (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025b) Risks and causes of testicular cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Cassidy, J., Bissett, D., Spene, R. and Payne, M. (2010) Oxford Handbook of Oncology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coupland, C.A.C., Chilvers, C.E.D., Davey, G., Pike, M.C., Oliver, R.T.D. and Forman, D. (1999). Risk factors for testicular germ cell tumours by histological tumour type. British Journal of Cancer, 80(11), pp.1859–1863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690611.

de Vries, G., Rosas-Plaza, X., van Vugt, M.A.T.M., Gietema, J.A. and de Jong, S. (2020). Testicular cancer: Determinants of cisplatin sensitivity and novel therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 88, p.102054. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102054.

Del Risco Kollerud, R., Ruud, E., Haugnes, H.S., Cannon-Albright, L.A., Thoresen, M., Nafstad, P., Vlatkovic, L., Blaasaas, K.G., Næss, Ø. and Claussen, B. (2019). Family history of cancer and risk of paediatric and young adult’s testicular cancer: A Norwegian cohort study. British Journal of Cancer, 120(10), pp.1007–1014. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0445-2.

Depue, R.H., Pike, M.C. and Henderson, B.E. (1983). Estrogen exposure during gestation and risk of testicular cancer Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 71(6), pp.1151-5.

Ferguson, L. and Agoulnik, A.I. (2013). Testicular Cancer and Cryptorchidism. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2013.00032.

Gaddam, S.J., Bicer, F., Chesnut, G. (2023) Testicular Cancer. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563159/ (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Garolla, A., Vitagliano, A., Muscianisi, F., Valente, U., Ghezzi, M., Andrisani, A., Ambrosini, G. and Foresta, C. (2019). Role of Viral Infections in Testicular Cancer Etiology: Evidence From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00355.

Haughey, B.P., Graham, S., Brasure, J., Zielezny, M., Sufrin, G. And Burnett, W.S. (1989). THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TESTICULAR CANCER IN UPSTATE NEW YORK. American Journal of Epidemiology, 130(1), pp.25–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115319.

Hemminki, K. and Chen, B. (2006). Familial risks in testicular cancer as aetiological clues. Andrology, 29(1), pp.205–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00599.x.

Kuczyk, M.A., Serth, J., Bokemeyer, C., Jonassen, J., Machtens, S., Werner, M. and Jonas, U. (1996). Alterations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in carcinoma in situ of the testis. Cancer, 78(9), pp.1958–1966. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961101)78:9%3C1958::aid-cncr17%3E3.0.co;2-x.

Lab Clinics (n.d) Role of DNA methylation in Disease Available at: https://www.labclinics.com/2018/11/08/role-dna-methylation-disease/?lang=en (Accessed: 3rd July 2025

Leslie, S.W., Sajjad, H. and Villanueva, C.A. (2020). Cryptorchidism. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29261861/ (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Looijenga, L.H., Gillis, A.J, Stoop, H., Hersmus, R. and Oosterhuis, J.W. (2007). Relevance of microRNAs in normal and malignant development, including human testicular germ cell tumours. International Journal of Andrology, 30(4), pp.304–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00765.x.

Loveday, C., Litchfield, K., Levy, M., Holroyd, A., Broderick, P., Kote-Jarai, Z., Dunning, A.M., Muir, K., Peto, J., Eeles, R., Easton, D.F., Dudakia, D., Orr, N., Pashayan, N., Reid, A., Huddart, R.A., Houlston, R.S. and Turnbull, C. (2017). Validation of loci at 2q14.2 and 15q21.3 as risk factors for testicular cancer. Oncotarget, 9(16), pp.12630–12638. doi:https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23117.

Park, J.S., Kim, J., Elghiaty, A. and Ham, W.S. (2018). Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine, 97(37), p.e12390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000012390.

Roland, J. (2024) What Are the Different Types of Testicular Cancer?. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/cancer/testicular-cancer-types (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Secondino, S., Viglio, A., Neri, G., Galli, G., Faverio, C., Mascaro, F., Naspro, R., Rosti, G. and Pedrazzoli, P. (2023). Spermatocytic Tumor: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 24(11), p.9529. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119529.

Swerdlow, A.J., Higgins, C.D. and Pike, M.C. (1997). Risk of testicular cancer in cohort of boys with cryptorchidism. BMJ, 314(7093), pp.1507–1507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7093.1507.

Leave a comment