Prevention and Treatment of Testicular Cancer

Surgery

Surgical orchiectomy

This is a standard technique for spermocytic tumours (ST) especially in complex cases where seminoma and ST are difficult to differentiate (Secondino et al., 2023). They rarely metastasis and this is alone treatment.

Counselling following orchiectomy

This takes place for several reasons for psychological comfort:

With procedures such as orchiectomy, there is a risk of infertility.

If the patient desired testicular prosthesis after having orchiectomy. This is an artificial implant to replace a testicle removed due to injury or cancer. The prosthesis is positioned in the scrotum. It helps to boost body image and self-esteem.

Sperm banking for patients with bilateral testicular pathology.

(Stephenson et al., 2019; Gilligan et al., 2019)

Chemotherapy

Aim and Objective On The Use Of Chemotherapy

The aim of chemotherapy is to kill cancer cells. This is commonly given as multiple regimen (several chemotherapies used together) when there is a high risk of reoccurrence or metastasis. To prevent the cancer coming back after removing the testicle (adjuvant chemotherapy).

Administration of Chemotherapy

It is either injected into the blood or via a drip intravenously. Some drugs are taken through small portable pump to take home. A thin short tube enters a vein in the arm per treatment.

A course has several cycles of treatment. A cycle is the time between one and the subsequent. Each treatment cycle lasts 3 weeks (21 days) and are given on set days (Cancer Research UK, 2025d).

Examples of chemotherapy used to treat testicular cancer

According to the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG), patients with disseminated non-seminoma (low or intermediate IGCCCG) are treated with chemotherapy after surgical removal of the affected testicle (Wang et al., 2021).

Amongst the common combined chemotherapy regimens applied are: four courses of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) or etoposide, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VIP). However, if there are residual disease after completing chemotherapy, dissection of associated lymph nodes and or metastases occurs. It is estimated that 10-15% of patient cases where the cancer has spread (disseminated disease) due to relapse or refractory disease will require second-line therapy (Adra and Einhorn, 2017). The type of salvage treatment whether surgery or chemotherapy or radiotherapy is depending on the initial combination therapy used in cisplatin and extent of residual disease.

The main combined chemotherapies are:

- bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP)

- etoposide and cisplatin (EP)

- vinblastine, ifosfamide, cisplatin (VeIP)

- etoposide, ifosfamide, cisplatin (VIP)

- paclitaxel (Taxol), ifosfamide, cisplatin (TIP)

- gemcitabine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (GIP)

(Cancer Research UK, 2025d)

There are potential risk of blood clots and are commonly prescribed with blood thinners or anti-coagulants to prevent blood clots (Cancer Research UK, 2025d).

Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplant

High dose of chemotherapy can be given alongside autologous stem cell transplant.

Autologous stem cell transplant in a patient uses their own stem cells for transplant leading to limited or null rejection by the immune system. Stem cells are undifferentiated cells that are used for growth and tissue repair and are able to self-renew. They can be extracted from an embryo during the early stages or it can performed from adult cells. In contrast, allogeneic stem cell transplant is given from a donor relative or non-relative. There are more complications via allogeneic transplantation.

The International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG)

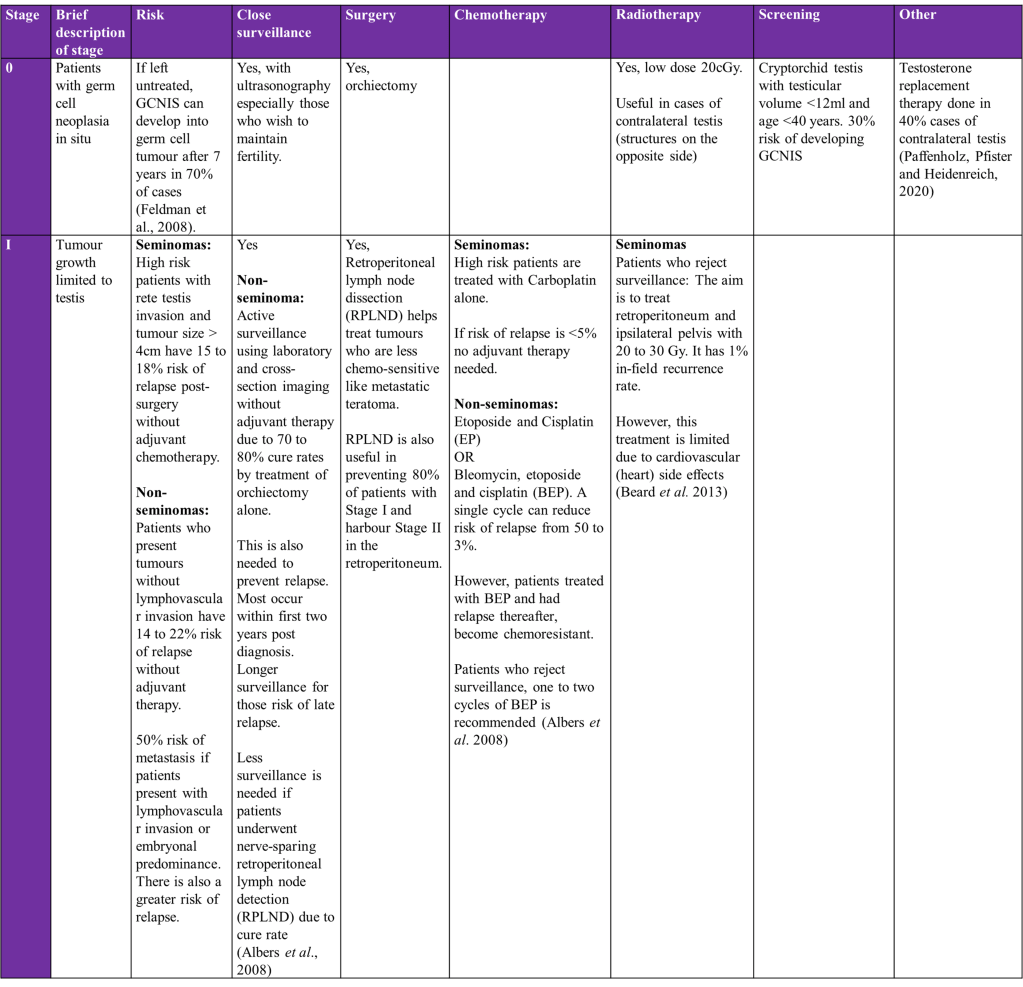

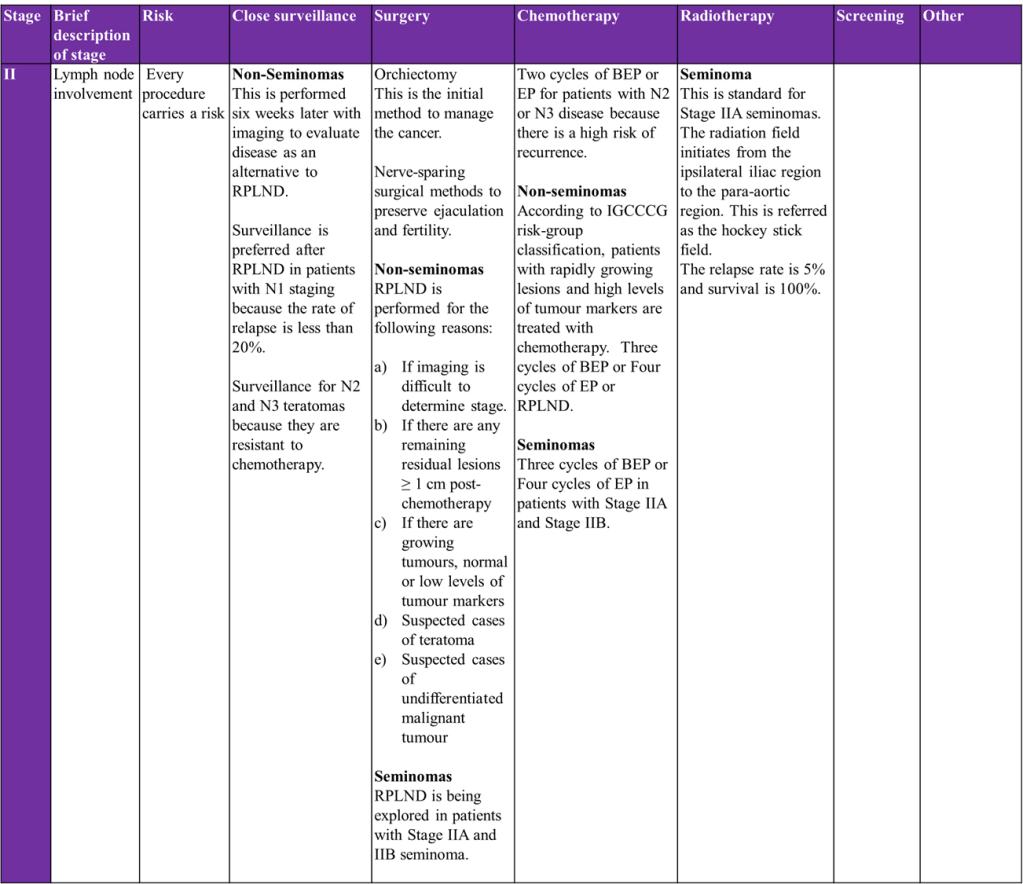

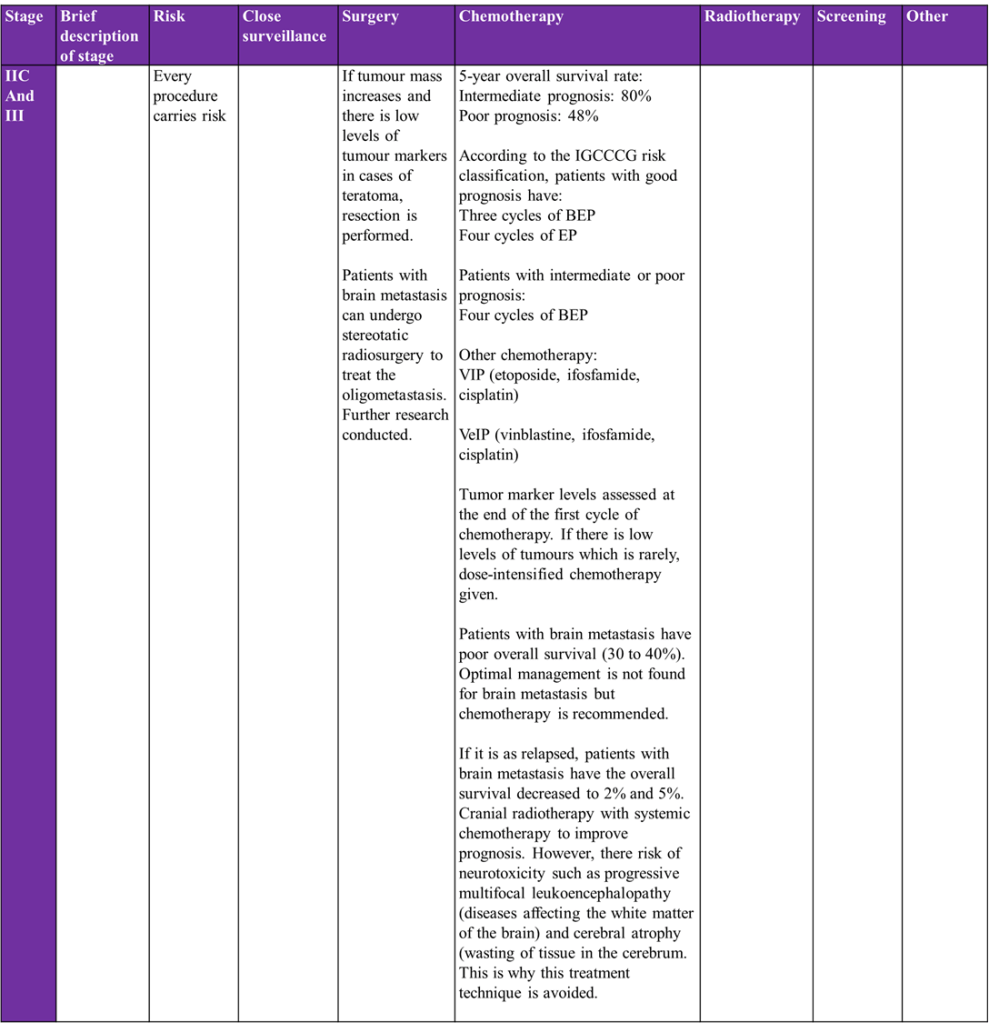

Overview of treatment strategies per clinical stage of testicular cancer was summarised from (Gaddam, Bicer and Chesnut, 2023)

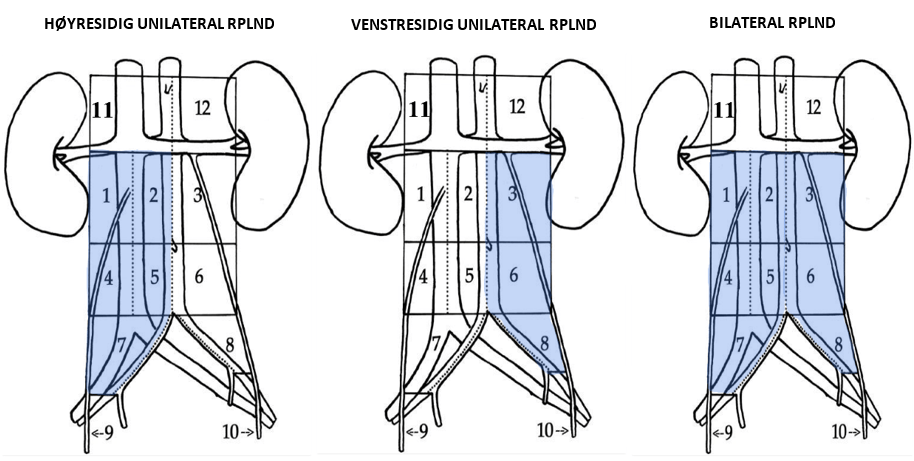

A) Right side unilateral RPLND B) Left side unilateral RPLND C) BILATERAL (Helsedirectoratet, n.d.)

(Gaddam, Bicer and Chesnut, 2023)

For further information on treatments for testicular cancer, please visit:

Cancer Research UK: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/treatment/treatment-decisions

Gaddam, S.J., Bicer, F., Chesnut, G. (2023) Testicular Cancer. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563159/

National Health Service: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/testicular-cancer/treatment/

New Research In The Diagnosis And Treatment In Testicular Cancer

Global progress has been made in researching changes in the genes in testicular cancer to learn more about the causes of testicular cancer. This will help personalise treatment and discover better drugs that target gene mutations.

Research Development One: New genetic markers identified

Recent research revealed that NANOG, SOX2, REX1, and PLAP help identify men at high risk of testicular cancer (American Cancer Society, 2025).

NANOG gene

The NANOG gene encodes for a DNA-binding homeobox transcription factor that can halt embryonic stem cell differentiation and autorepress its expression in differentiating cells. Other functions are in cell renewal and pluripotency. Pluripotency can differentiate into any of the three germ cells (ectoderm, endoderm, or mesoderm) to form a mature organism (GeneCards, 2025).

SOX2 gene

SOX2 (SRY-related HMG-box) gene is a transcription factor that regulates embryonic development and identifies cell fate. It is involved in the stem-cell maintenance in the central nervous system and stomach (National Library of Medicine, 2025).

Rex1 gene

Rex1 (zfp42) is a zinc finger protein expressed in undifferentiated embryonic and adult stem cells. Disruption of Rex1 increases expression of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Rex1 has other roles, including cell cycle regulation and cancer progression (Scotland et al., 2009).

PLAP gene

Placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) is a membrane enzyme encoded by the ALPP gene on chromosome 2, expressed in the placenta. Basiri and Pahlavanneshan (2021) discovered a two-fold increase in ovarian, testicular germ cell, and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. It is also expressed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia, and other cancers but limited, suggesting that PLAP can serve as a tumour-specific antigen (Basiri and Pahlavanneshan, 2021).

Research Development Two: Exploring mechanisms of cisplatin resistance

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy combined with the refinement of surgical procedures has greatly improved patient survival rates. Conversely, there is a tendency to have relapse after salvage chemotherapy, and optimum therapy is not apparent.

The mode of action of Cisplatin

Cisplatin is a platinum-based drug used as a first-line therapy for many solid tumours including testicular cancers (Wang et al., 2021). It enters the cancer cell through a copper trafficking system where copper transport (Ctr) protein, Ctr1 and Ctr2, facilitate cisplatin transport via passive diffusion (Kilari, Guancial and Kim, 2016).

Cisplatin is inert (unreactive) and requires activation to enter the cell. At low chloride concentrations, the chloride ion present in cisplatin (cis-chloro group) is replaced with water molecules. This reaction is referred to as aquation and allows the activation of cisplatin.

The activated cisplatin can enter the nucleus and affect transcription of target genes, which facilitates its anticancer response. The binding of cisplatin to DNA results in internal and interchain crosslinks. This prevents DNA replication and transcription, and induces DNA damage. Other ion pumps involved in the pumping of cisplatin are ATP7A and ATP7B (Wang et al., 2021).

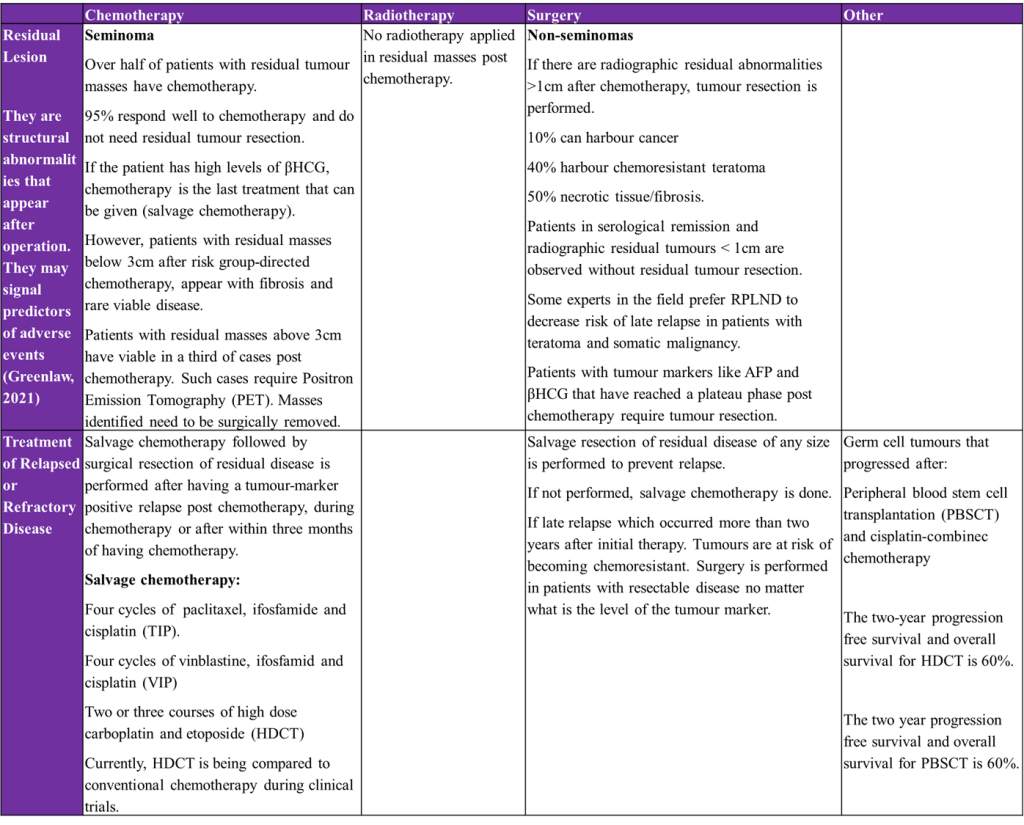

Methods of Cisplatin Resistance

Research efforts have been made to identify molecular mechanisms underlying cisplatin resistance. Currently, Phase 2 studies with targeted agents have not presented clear efficacy (Chovanec and Cheng, 2022). However, PARP, MDM2, or AKT/MTOR combined with cisplatin have shown positive results in pre-clinical studies (de Vries et al. 2020). Ongoing Xenograft studies are used to determine and validate novel therapies. It is estimated that 10-20% of TC patients with metastasis cannot be treated with cisplatin. A reduction in the influx by CTR1 transmembrane protein and increased drug efflux by Pgp glycoprotein and MRP1 (ABC transporter channels) can lower cisplatin-toxicity and concentration of cisplatin inside the cell (Holzer, Manorek, and Howell, 2006; Liedert et al., 2003).

Another resistance mechanism is the increased sequestration of cisplatin by glutathione (GSH). Glutathione is present in the cytoplasm of cells and binds with cisplatin via the enzyme Glutathione S-transferases (GST). The conjugation with the therapeutic drug facilitates the GSH detoxification system, increasing the removal of cisplatin from cancer cells (Mandic et al., 2003). This prevents cisplatin from translocating to the nucleus to induce DNA strand breaks (Kumar, Kushwaha, and Gupta, 2019). Tumour suppressor genes Nrf2 and p21 also partake in cisplatin resistance via regulation of GSH metabolism.

Cisplatin resistance also affects genetics and epigenetic mechanisms. Cancer cells can survive the DNA lesions and can increase DNA repair of the cisplatin-induced molecular damage. Several DNA repair mechanisms, namely NER, non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination (Wang et al., 2021).

Cancer cells can evade apoptotic signals by downregulating pro-apoptotic genes and upregulating anti-apoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 protein family (de Vries et al., 2020). Amongst the examples of genes downregulated in PUMA (p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) and NOXA. PUMA partakes in p53-dependent and independent apoptosis, regulated by transcription factors. NOXA, otherwise known as Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-Acetate-Induced Protein 1, normally mediates stress. This influences how activation of proapoptotic molecules leads to apoptotic mechanisms in response to DNA damage. OCT4 is also downregulated and is a homeodomain transcription factor that is involved in the self-renewal of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells.

Other methods for increasing cancer survival are the prevention of the FAS/FASL ligand system of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Mutational changes to the tumour suppressor p53 can also evade apoptosis. There are additional signalling pathways that can influence cisplatin action and regulate its resistance. PI3K/AKT/mTOR crosstalk with JNK, RAS-ERK, NF-KB, Nrf2, and STAT3 to stimulate apoptosis, cell differentiation, survival, and growth (Rinne et al., 2022; Matsuoka and Yashiro, 2014).

References

Adra, N., and Einhorn, L. H. (2017). Testicular Cancer Update. Clinical Advances in Hematology and Oncology, 15 (5), pp.386–396.

Albers, P., Siener, R., Krege, S., Schmelz, H.-U., Dieckmann, K.-P., Heidenreich, A., Kwasny, P., Pechoel, M., Lehmann, J., Kliesch, S., Köhrmann, K.-U., Fimmers, R., Weiβbach, L., Loy, V., Wittekind, C. and Hartmann, M. (2008). Randomized Phase III Trial Comparing Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection With One Course of Bleomycin and Etoposide Plus Cisplatin Chemotherapy in the Adjuvant Treatment of Clinical Stage I Nonseminomatous Testicular Germ Cell Tumors: AUO Trial AH 01/94 by the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(18), pp.2966–2972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.0899.

American Cancer Society (2025) What’s New in Testicular Cancer Research? Available from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/testicular-cancer/about/new-research.html (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Basiri, M and Pahlavanneshan, S. (2021). Evaluation of Placental Alkaline Phosphatase Expression as A Potential Target of Solid Tumors Immunotherapy by Using Gene and Protein Expression Repositories. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals), 23(6), pp.717–721. doi:https://doi.org/10.22074/cellj.2021.7299.

Beard, C.J., Travis, L.B., Chen, M.-H., Arvold, N.D., Nguyen, P.L., Martin, N.E., Kuban, D.A., Ng, A.K. and Hoffman, K.E. (2013). Outcomes in stage I testicular seminoma: A population-based study of 9193 patients. Cancer, 119(15), pp.2771–2777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28086.

Cancer Research UK (2025c) Treatment options for testicular cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/treatment/treatment-decisions (Accessed: 4th July 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025d) Chemotherapy for Testicular Cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/treatment/chemotherapy-treatment (Accessed: 4th July 2025)

Chovanec, M. and Cheng, L. (2022). Advances in diagnosis and treatment of testicular cancer. BMJ, p.e070499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070499.

de Vries, G., Rosas-Plaza, X., van Vugt, M.A.T.M., Gietema, J.A. and de Jong, S. (2020). Testicular cancer: Determinants of cisplatin sensitivity and novel therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 88, p.102054. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102054.

Feldman, D.R., Bosl, G.J., Sheinfeld, J. and Motzer, R.J. (2008). Medical Treatment of Advanced Testicular Cancer. JAMA, 299(6), p.672-84 doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.6.672.

Gaddam, S.J., Bicer, F., Chesnut, G. (2023) Testicular Cancer. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563159/ (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

GeneCards (2025) GeneCards Symbol: NANOG. Available at: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=NANOG (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Gilligan, T., Lin, D.W., Aggarwal, R., Chism, D., Cost, N., Derweesh, I.H., Emamekhoo, H., Feldman, D.R., Geynisman, D.M., Hancock, S.L., LaGrange, C., Levine, E.G., Longo, T., Lowrance, W., McGregor, B., Monk, P., Picus, J., Pierorazio, P., Rais-Bahrami, S., Saylor, P., Sircar, K., Smith, D.C., Tzou, K., Vaena, D., Vaughn, D., Yamoah, K., Yamzon, J., Johnson-Chilla, A., Keller, J., Pluchino, L.A.. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 17(12), pp.1529-1554.

Greenlaw, E. (2021) New study ties residual lesion score (RLS) to cardiac surgery outcomes. Available at: https://answers.childrenshospital.org/rls/ (Accessed: 4th July 2025)

Helsedirektoratet (n.d) 9.1. (RPLND) Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/testikkelkreft-handlingsprogram/annen-kirurgi-enn-orkiektomi/rplnd (Accessed: 4th July 2025)

Holzer, A.K., Manorek, G.H. and Howell, S.B. (2006). Contribution of the Major Copper Influx Transporter CTR1 to the Cellular Accumulation of Cisplatin, Carboplatin, and Oxaliplatin. Molecular Pharmacology, 70(4), pp.1390–1394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.106.022624.

Kilari, D. (2016). Role of copper transporters in platinum resistance. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 7(1), pp.106-113 doi:https://doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v7.i1.106.

Kumar, S., Kushwaha, P.P. and Gupta, S. (2019). Emerging targets in cancer drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resistance. doi:https://doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2018.27.

Liedert, B., Materna, V., Schadendorf, D., Thomale, J. and Lage, H. (2003). Overexpression of cMOAT (MRP2/ABCC2) Is Associated with Decreased Formation of Platinum-DNA Adducts and Decreased G2-Arrest in Melanoma Cells Resistant to Cisplatin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 121(1), pp.172–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12313.x.

Mandic, A., Hansson, J., Linder, S. and Shoshan, M.C. (2003). Cisplatin Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Nucleus-independent Apoptotic Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(11), pp.9100–9106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m210284200.

Matsuoka, T. and Yashiro, M. (2014). The Role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling in Gastric Carcinoma. Cancers, 6(3), pp.1441–1463. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers6031441.

National Library of Medicine (2025) SOX2 SRY-box transcription factor 2. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/6657 (Accessed: 3rd July 2025)

Paffenholz, P., Pfister, D. and Heidenreich, A. (2020). Testis-preserving strategies in testicular germ cell tumors and germ cell neoplasia in situ. Translational Andrology and Urology, 9(S1), pp.S24–S30. doi:https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2019.07.22.

Rinne, N., Christie, E.L., Ardasheva, A., Kwok, C.H., Demchenko, N., Low, C., Tralau-Stewart, C., Fotopoulou, C. and Cunnea, P. (2021). Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in epithelial ovarian cancer, therapeutic treatment options for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancer Drug Resistance, [online] 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2021.05.

Scotland, K.B., Chen, S., Sylvester, R. and Gudas, L.J. (2009). Analysis of Rex1 (zfp42) function in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Developmental Dynamics, 238(8), pp.1863–1877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.22037.

Secondino, S., Viglio, A., Neri, G., Galli, G., Faverio, C., Mascaro, F., Naspro, R., Rosti, G. and Pedrazzoli, P. (2023). Spermatocytic Tumor: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 24(11), p.9529. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119529

Stephenson, A., Eggener, S.E., Bass, E.B., Chelnick, D.M., Daneshmand, S., Feldman, D., Gilligan, T., Karam, J.A., Leibovich, B., Liauw, S.L., Masterson, T.A., Meeks, J.J., Pierorazio, P.M., Sharma, R. and Sheinfeld, J. (2019). Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline. Journal of Urology, 202(2), pp.272–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000000318.

Wang, L., Zhao, X., Fu, J., Xu, W. and Yuan, J. (2021). The Role of Tumour Metabolism in Cisplatin Resistance. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.691795.

Updated July 2025 Next Review April 2027

Leave a comment