Original author: Dr Shraddha Bhange

Original published date: 6th March 2014

Article updated by: Dr Hafsa Waseela Abbas

Update date: April 2025

Review date: April 2027

About

Dr Shraddha Bhange is a trained doctor and experienced safety physician. She is also one of the Board members of the ThinkSharp Foundation. Upon setting up the FST in 2014, Dr Bhange was among the initial supporters who wrote a one-off article voluntarily.

Cancer is the overgrowth of cells and contradicts how normal cells divide and grow. It results from neoplasia and tumour cells having abnormal shapes, and altered plasma membranes containing distinctive tumour antigens. The cells undergo unregulated proliferation and differentiation, which can result in invasive growth that forms unorganized cell masses. This reversion of a primitive or less differentiated state is called anaplasia.

Many causes and risk factors of cancer have intrinsic and extrinsic origins. It is classified into physical, biological, and chemical factors and the environment. Cancer-causing chemicals are referred to as carcinogens and can be found in processed food, drinks, pollution, and tobacco smoke. However, the risk of some cancers is associated with genetically inherited from parents and or family history where there are genetic mutations, and errors in DNA (World Health Organisation, 2025; Yusuf, Sampath and Umar, 2023). People who have problems with their immune systems, particularly inflammatory responses are more likely to get certain types of cancer. This group includes people who have had organ transplants and take drugs to suppress their immune systems to stop organ rejection, have Autoimmunodeficiency (AIDs), or were born with rare medical syndromes that affect their immunity levels (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023).

Genetics And Cancer

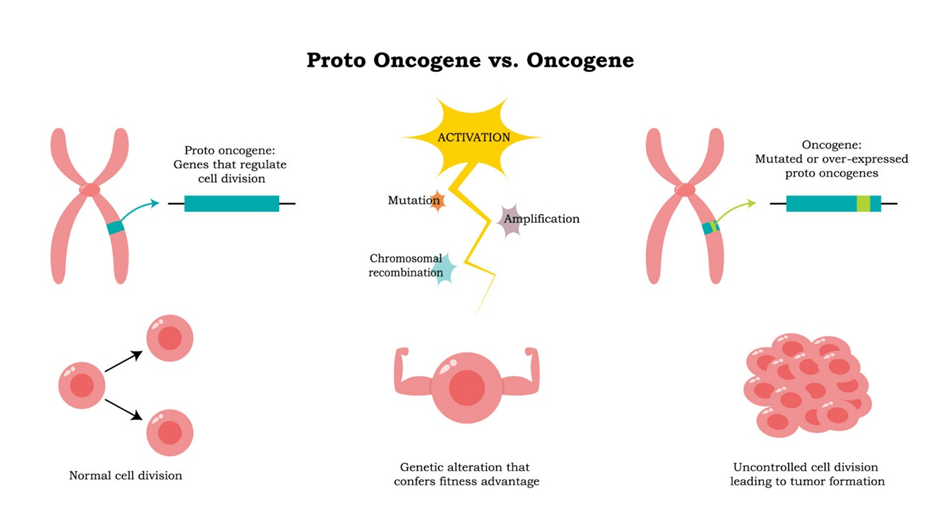

Genes are the short sections of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that carry genetic information. Proto-oncogenes are the ‘good’ genes that control how the cell grows and divides. However, when a mutation occurs causing a change in the gene or there are high levels of the gene expression, this transforms it to be a ‘bad’ gene called oncogene, for example, RAS. There is a loss of control which can result in cancer – please see Figure 1 (Brooker et al., 2008). Damaged or senescent cells (old) undergo a programmed cell death (apoptosis). Activated oncogenes can cause those cells to survive and proliferate. Most oncogenes require additional factors, for instance, genetic mutations and or environmental factors.

Having close relatives in the family who have cancer can increase the chance of carcinogenesis and progression. For example, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is caused by changes in the APC gene and is presented as polyps in the intestines (bowel). Being born with an inherited genetic mutation does not necessarily suggest that a person will get cancer (Cancer Research UK, 2024a). Patients or relatives that have FAP increase the chance or likelihood of developing colorectal cancer and other types of cancer (National Cancer Institute, 2024).

Moreover, having many relatives with cancer does not suggest there is a cancer gene within the family. Several factors influence the risk of cancer via family history: the relation in the family, level of generation (how close they are), type of cancer, and the age of the relative at the point of diagnosis (Cancer Research UK, 2024). It is estimated, that the younger the relative was, the more relatives who had this form of cancer, the stronger the family history is.

Figure 1: An overview of the transformation of a proto-oncogene to oncogene.

An insight into DNA.

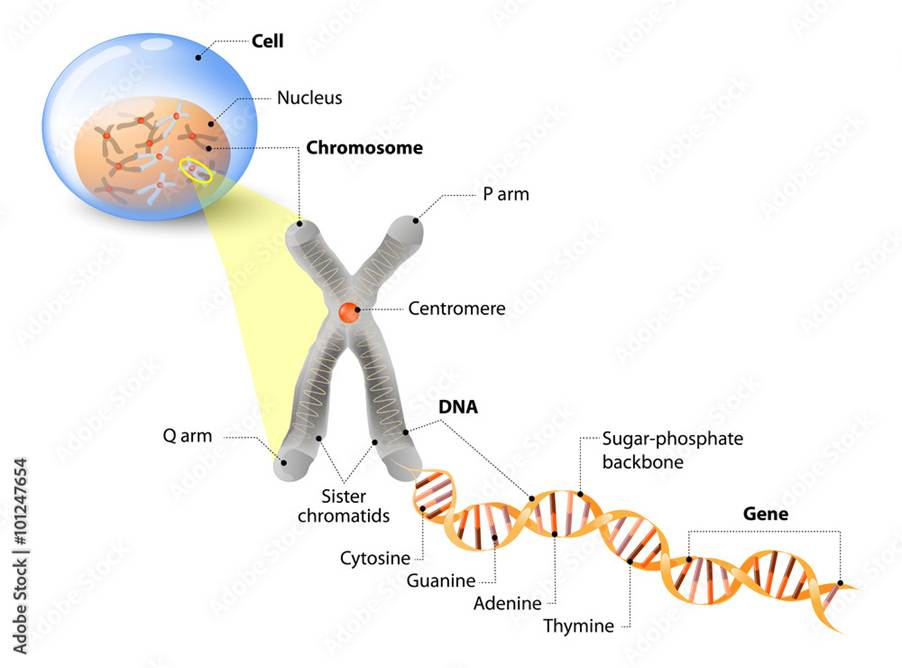

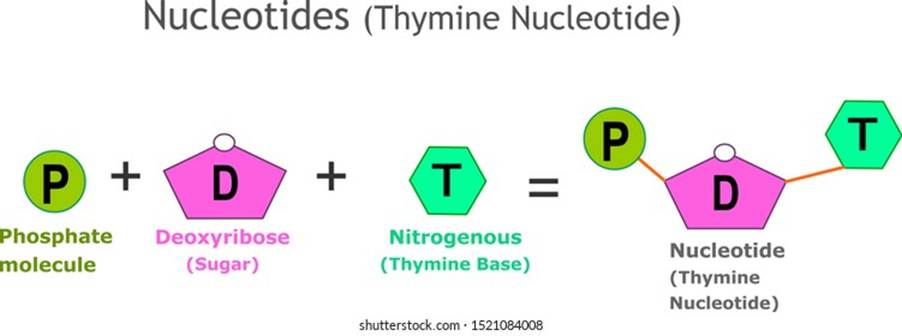

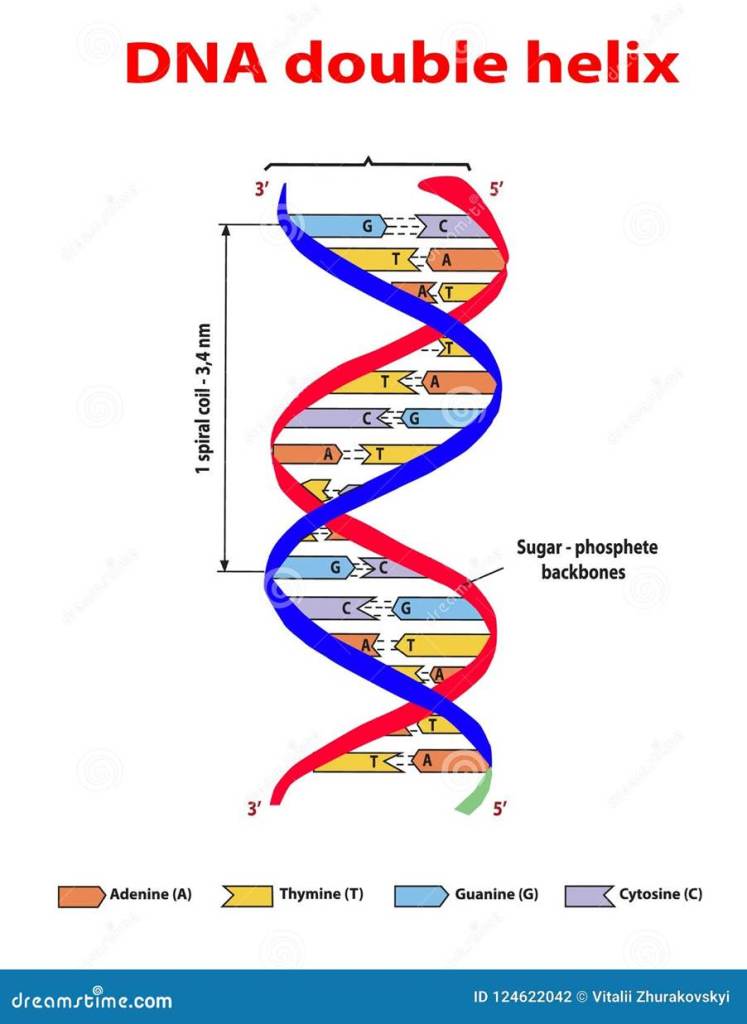

In the nucleus, there are threadlike structures called chromosomes containing the DNA. The DNA molecule has genetic information to control the cell. The gene is in a fixed position called the locus on the DNA where each gene codes for a protein. The DNA consists of many nucleotides bound together to form a polynucleotide – please see Figure 2. Each nucleotide contains a phosphate, five-carbon deoxyribose sugar, and nitrogenous base. The phosphate group is negatively charged and provides the DNA with acidic properties. It is attached to the 5’ carbon of the sugar molecule. Deoxyribose sugar refers to the sugar losing an oxygen atom ‘de-oxy’. There are four nitrogenous bases: cytosine ( C), Guanine (G), Thymine (T), and Adenine (A). They have specific complementary base pairing to express the genetic material: Adenine with Thymine whereas Cytosine associates with Guanine (Brooker et al., 2008). The structure of the nucleotide illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2: The level of organisation within the nucleus to the gene.

Figure 3: The formation of a nucleotide using an example of a thymine

A polynucleotide has a free phosphate group at one end, called the 5′ end. The phosphate group is bound to position carbon 5′ of the ribose sugar to form the sugar-phosphate backbone. There is a 3’ end where a hydroxyl (-OH) group is in position carbon 3’ of the ribose sugar. In 1953, the structure of DNA was discovered by four scientists, Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins using X-ray crystallography. They found two polynucleotide strands wounded together by hydrogen bonding to strengthen and stabilise its structure from damage – please see Figure 4 (Brooker et al., 2008).

Figure 4: The structure of the DNA molecule.

Genetic mutations can occur through inherited or chemical exposure in the environment – please see Figure 5 (National Cancer Institute, 2024). Cancer can be inherited (passed down) if it is present in the father’s sex cell (sperm) or the mother’s sex cell (egg). For instance, a mutated BRCA1 or 2 increases the risk of breast, and ovarian cancer and other cancers (National Cancer Insitute, 2024). If a parent has a gene change, each child has a 1 in 2 chance (50%) of inheriting it (Cancer Research UK, 2024a).

Figure 5: Some of the types of genetic mutations that can occur in cancer.

Physical factors

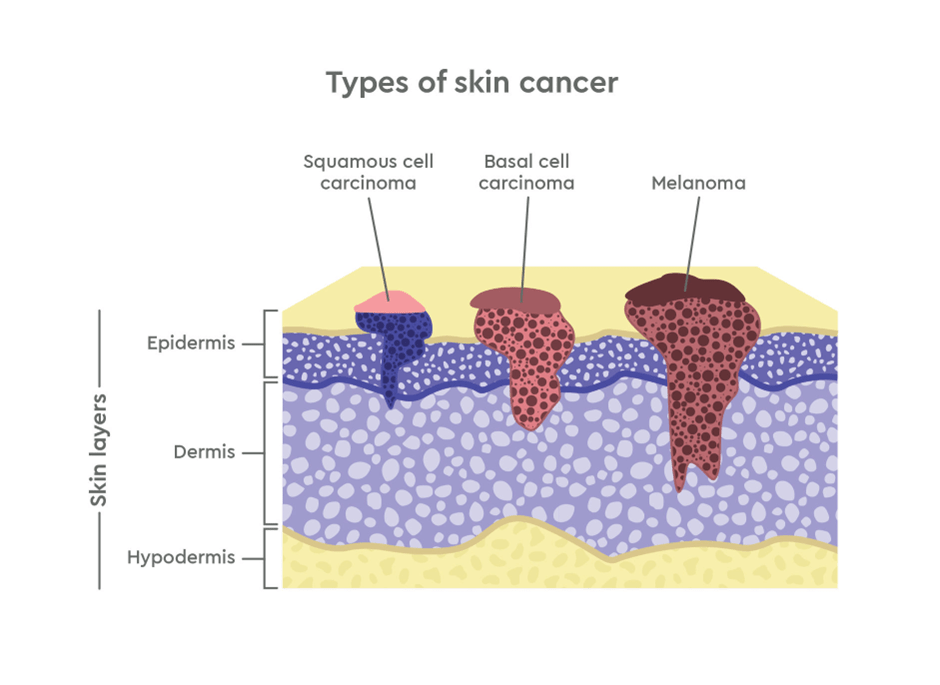

The largest source of Vitamin D is the sun; it helps to strengthen teeth and bones. However, unbalanced sun exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and the use of sunscreen beds can cause skin cancer and wrinkles. This is preventable if suncream is used and is also treatable (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Children and people of Caucasian origin are at the most risk, particularly in the back for non-melanoma. The face and ears can increase basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin – please see Figure 6 (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Figure 6: Types of skin cancer (genesiscareus.com)

There are different types of UV radiation: A, B, and C, and the ability of the type of UV to penetrate the skin increases the danger. Overexposure to UVA radiation can cause skin cancer, wrinkles, tanning, and a burning sensation. The UV light can damage protein fibers in the skin called elastin causing stretch. UVB radiation can damage the outer layer of skin (epidermis) causing burns, blisters, tanning, and sun spots (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Actinic keratosis and lesions may appear if the immune system decreases taking longer to heal. In contrast, UVC has less chance of causing cancer because it is absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere – please see Figure 7.

Ionizing radiation

Several sources emit radiation particularly X-rays, gamma rays, and other examples. Low energy radiation has a limited risk of causing DNA damage and cancer, for instance, mobile phones and visible light. High exposure especially 500 to 2000 mSv can form blood cancers like leukaemia (Cassidy et al., 2010; National Cancer Institute, 2019). Increased risk of scanning medical procedures such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography (PET) can induce cellular and DNA damage leading to cancer. However, the risk is minimal and the benefits outweigh the risk (National Cancer Institute, 2019). For instance, the CT scan has higher radiation than an ordinary X-ray and equals the natural radiation received from the atmosphere for approximately three years, the added risk is minimal and risks missing a serious disorder or condition of not having a CT scan should be considered.

Figure 7: The three types of UV radiation.

Biological Factors

Viruses

The World Health Organisation (2025) estimated that 13% of cancers are caused by bacteria and viruses namely, Helicobacter pylori (bacteria), Hepatitis B (virus), Hepatitis C (virus), Human Papillomavirus (virus) and Epstein-Barr (virus). Other sources of evidence suggest they account for 20% of tumours (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023). They have the potential to change a normal cell into a tumour cell. This process is called transformation.

Viruses known to cause cancer are called oncoviruses. These cancers are preventable by avoiding risk factors through evidence-based preventative interventions. EBV (Epstein Barr virus) is one of the best-studied human cancer viruses. EBV is a herpes virus and can cause two cancers. Burkitt’s lymphoma is a malignant tumour of the jaw and abdomen (belly) found in children by age 3, particularly in equatorial Africa where malaria appears to be a contributing factor. EBV also causes nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the upper throat behind the nose. Burkitt’s lymphoma has a high level of antibodies in the blood compared to EBV (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Hepatitis B virus appears to be associated with one form of liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) and can be integrated into the human genome. It begins as a liver infection, followed by injury, and then chronic hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) (Cassidy et al., 2010). Hepatitis C causes cirrhosis of the liver, which can lead to liver cancer. Human herpes virus 8 and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) are associated with Kaposi sarcoma; a malignant tumour arising through the blood vessels of the skin. Patients with such cancers have low immune responses. The World Health Organisation (2025) reported that infections with HIV increase the risk of developing cervical cancer six-fold and substantially increase the risk of developing Kaposi sarcoma.

Structure of the virus

A virus is a subcellular obligate organism that varies in size with a diameter within the range of 10-400 nm. Some cancers such as smallpox virus are 200nm whereas parvovirus is between 18 and 22nm. Some can be observed through a light microscope whereas larger viruses through advanced microscopic systems e.g. electrons (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007). The structure of viruses contains either DNA or RNA and is wrapped in a protein coat called capsid – please see Figure 8. They depend on the host cell for their replication (copies) and metabolism (energy-forming reactions). Some viruses such as influenza have additional proteins on their surface: haemagglutinin, neuraminidase, and matrix proteins. Other viruses have carbohydrates and lipids on their surfaces (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007).

Viruses are also classified on where they exist. Extracellular viruses contain several enzymes and cannot reproduce without the host living cell. Intracellular viruses replicate their genome so small viruses (virions) are produced and can induce host metabolism. Enzymes such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; an enzymes used to produce RNA by using it as a template (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007).

Figure 8: Structure of the virus.

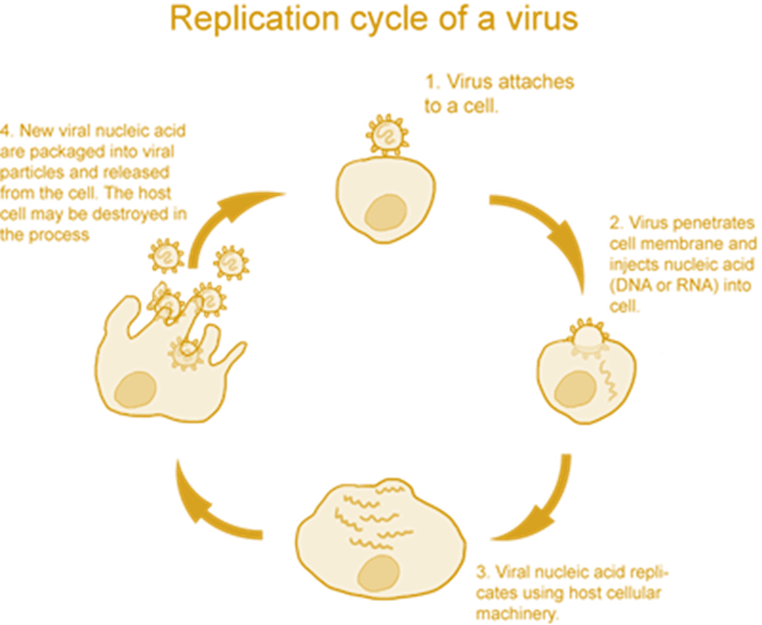

The replication and growth of viruses have five phases: adsorption, penetration, replication, assembly of viral capsid, and virion release – please see Figure 9. Adsorption is where the virus attaches to the cell by interacting with the receptor proteins on the cell surface. Most are glycoproteins (sugar head and protein tail) and are involved in the immune system. Glycoproteins can join hormones or other molecules to help the cell to function appropriately. Some viruses are specific to particular organisms or tissues within the host. Lipid rafts help viruses to enter as many of its receptors of enveloped viruses can bypass these protective barriers and enter the host cell (endocytosis). Some viruses can inject nucleic acid. Other viruses ensure the RNA/DNA polymerase enzyme can enter the host cell to produce viral DNA and RNA in the nucleus. Other viruses halt the host’s DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis and can stimulate its macromolecules. Late genes produce capsid proteins around the new virions (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007).

Figure 9: The replication process of viruses

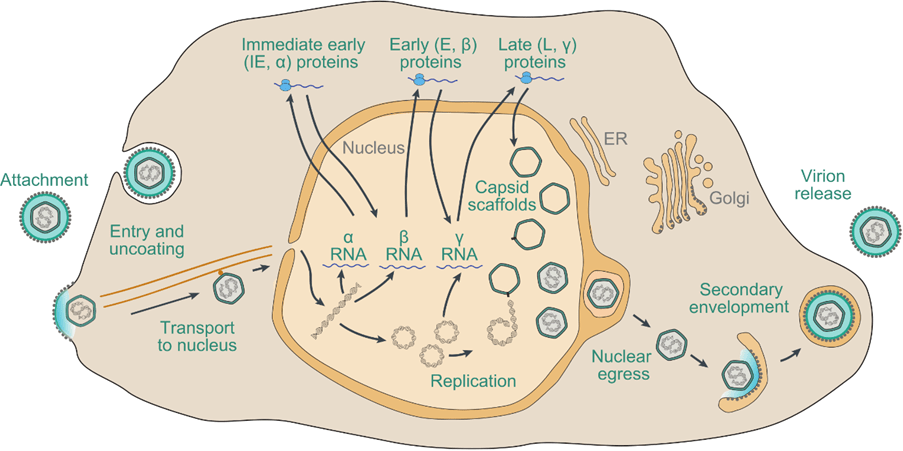

There are different ways to release new enveloped and naked viruses (non-enveloped). Naked viruses break the host cell (lysis) and enveloped viruses have multiple steps before being released – please see Figure 10. Virus-encoded proteins are incorporated into the plasma membrane. The nucleocapsid is released and the envelope is formed via the budding process.

In many viral families, a matrix (M) protein attaches to the plasma membrane and aids in the budding process. Most envelopes arise from the plasma membrane. In the herpes virus, the budding and the envelope formation usually involve the nuclear membrane. Golgi apparatus, ER, and other internal membranes may facilitate. Actin filaments can further aid in virion release. Many viruses change the actin microfilaments in the host cell cytoskeleton (Sherwood, Woolverton, and Willey, 2007).

Figure 10: Herpes viral replication cycle.

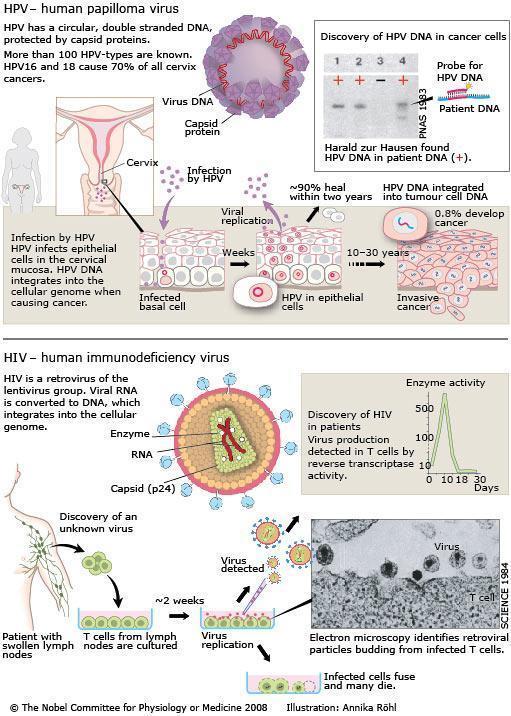

Human Papillomavirus and cancer

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) is a sexually acquired infection that affects the squamous epithelial cells presented in Figure 11. It is a small, non-enveloped, circular, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) oncoviruses of the Papillomaviridae family in developed countries (Pal and Kundu, 2020). There is strong evidence that more than 80% of cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV type 16 and 18 (Cassidy et al., 2010). HPV can encode proteins that bind to and inactivate tumour suppressor proteins. For instance, the major HPV protein E6 interacts with p53, a tumour suppressor protein that normally activates the transcription of p21. P21 is an inhibitor of the protein kinase enzymes that promote cell division (mitosis) for growth and repair (Pal and Kundu, 2020).

Figure 11: An overview of how HPV and HIV are able to replicate and affect target cells.

The E6 oncoproteins in HPV are one of the main players in the progression of cervical cancer. E6 in HPVs are at high risk of causing cancer and can form a complex with p53. p53 is an important tumour suppressor that directs the cellular response to genotoxic and cytotoxic stresses that threaten genomic stability (Pal and Kundu, 2020). It functions as a sequence-specific transcription activator necessary to regulate cell growth and tumour growth suppression. The p53 protein suppresses cell growth by transcriptionally activating p21, which inhibits the cell-cycle kinases critical for G1 progression and cell growth – please see Figure 12.

Studies have shown HPV E6 can induce degradation of p53 through ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. E6 forms a complex with the cellular ubiquitin-protein ligase E6-AP; they can bind and ubiquinate p53 (Pal and Kundu, 2020).

p53 stimulates G1 growth arrest or induces apoptosis in the cell to allow the host DNA to be repaired or to eliminate the cell if the DNA is irreparable. E6-expressing cells do not manifest a p53-mediated cellular response to DNA damage, which leads to genomic instability. E6 can also activate telomerase independent of p53, leading to immortalization of the infected cell. There is also evidence that E6 can induce abnormal centrosome duplication, leading to genomic instability and aneuploidy. This presents the various mechanisms to unstabilize the genome.

E2F is a cell-cycle activator regulated by the binding of pRB, a cellular tumor suppressor – please see Figure 11. HPV protein E7 can bind to pRB, rendering it unable to bind and regulate E2F, which then can freely activate the cell cycle to progress uncontrollably (Pal and Kundu, 2020).

Figure 12: The link between the oncoproteins of HPV and p53 crosstalk (Creative Commons, 2025)

Bacteria

The ubiquity of bacteria is common in the aetiology of human infection and diseases, particularly cancer. For example, Chlamydia infections increase the risk of cervical cancer particularly in patients with HPV. One of its subtypes is Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is found to increase lung cancer. Salmonella typhi infections have a higher risk of gallbladder cancer (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023). Bacteria can act as carcinogens promoting tumour progression by producing enzymes, toxins, and proteins to increase inflammation, dysregulate signaling pathways, affect cell cycle control, and target host cell DNA (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023).

Bacterial infections can also occur during and after cancer treatment particularly in patients with blood cancers with Pseudomonas Aeroginosa who have undergone surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. There is a tendency to have low levels of neutrophils (neutropenia) and the use of immunosuppressive drugs and is prone to infection. This significantly causes infection-related mortality (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023). An epidemiological study discovered that bacterial infections have an eight-fold than solid tumours. Increased susceptibility to bacterial infections can also correlate to antibiotic resistance and lower survival rates. Thus, monitoring cancer patients is essential.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium that lives on the stomach epithelial linings. Its strains have different carcinogenic potentials due to their properties, host response, and environmental risk factors that affect pathogen-host interactions (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023). Many can develop inflammation of the stomach lining raising the risk of intestinal metaplasia and stomach cancer in developed countries (Cassidy et al., 2010). It can affect predominantly children and is transmitted via mouth and faeces.

H.pylori can adapt to the acidic environment and cause pathogenesis for years because of its locomotion, synthesis of the urease enzymes, and secretion of the cytotoxin; VacA. The VacA can affect mitochondria modify the plasma membrane, and promote apoptosis by influencing the activity of the mitochondria to suppress the proliferation of T-cells (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023).

H. pylori infections promote inflammation of the gastric mucosal lining. It can also cause chronic infections or transplanted organs can continually stimulate cells to divide. This continual cell division means cells such as immune are more likely to develop genetic faults into lymphomas (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023).

Another explanation of the link between bacteria and cancer is the human microbiome which consists of bacteria, fungi, and viruses found in the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems. The bacterial population predominantly contains 500-1000 different species in the gut (Yusuf, Sampath and Umar, 2023). The commensal bacteria in the gut facilitate digestion, absorption of nutrients, metabolize indigestible chemicals, modulate the immune system, and prevent the colonization of bacterial pathogens. An imbalance between host-bacterial interactions is referred to as dysbiosis and this causes cancer and gastrointestinal conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and diabetes (Yusuf, Sampath, and Umar, 2023).

Parasites

Parasitic infections such as Schistosomiasis haematobium are associated with dysplasia and invasive cancer of the bladder contributing to 8% of cases of squamous cell carcinoma (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Chemical Factors

Tobacco smoke

Tobacco smoke is a powerful carcinogen but not everyone who smokes gets lung cancer despite it being a causative agent in 80% of its cases. Passive smoking contributes to 15-30% of cases. Several chemicals can increase lung cancer – please see Figure 13. It also contributes to myeloid leukaemia, and gastrointestinal cancers of the stomach, mouth, oesophagus, and pancreas. Other organs are also at risk: ears, nose and throat (ENT), bladder, kidney, liver, and cervical (Cassidy et al., 2010). Smoking can damage the DNA of cells and make it harder to repair as presented in Figure 14. It has a synergistic effect on developing neoplasms caused by other carcinogens such as alcohol and asbestos (Cassidy et al., 2010).

Figure 13: Chemicals found in the cigarette smoke.

Figure 14: How does smoking cause cancer.

Alcohol

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (2025) estimated that 741,000 new cases of cancer globally in 2020 were associated with alcohol consumption. Alcohol (>2 units) was implicated in 86% of the total alcohol-attributable cases. Light to moderate drinking has up to two alcoholic drinks per day represented 1 in 7 alcohol-attributable cases and accounted for more than 100,000 new cancer cases worldwide. It contributes to increasing the incidence of several cancers presented in Figure 15, particularly head and neck, squamous oesophageal, and breast cancer (24% of cases). Oestrogens and androgens have a role besides the continuous secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inflamed adipocytes can elicit epigenetic changes in pre-cancerous cells to increase cancer (Ratna and Mandrekar, 2017). Alcohol cirrhosis can cause liver cancer. Non-cirrhotic liver caused by Hepatitis B infection and mutations of the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) that encode the Beta-catenin protein involved in the Wnt signaling pathway for cellular growth control (Ratna and Mandrekar, 2017).

Figure 15: Cancers that are attributed to alcohol drinking (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2025).

There are several ways in how alcohol can cause cancer – please see Figure 16. The enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase oxidises alcohol (ethanol) to form acetaldehyde (Ratna and Mandrekar, 2017). Acetaldehyde induce DNA damage and other genotoxic effects. Inflammation and oxidative stress blocks DNA repair and impairs Vitamin B12 metabolism increasing the risk of anaemia (Rumgay et al., 2021).

Figure 16: Pathogenesis in how alcohol causes cancer.

Occupational exposure

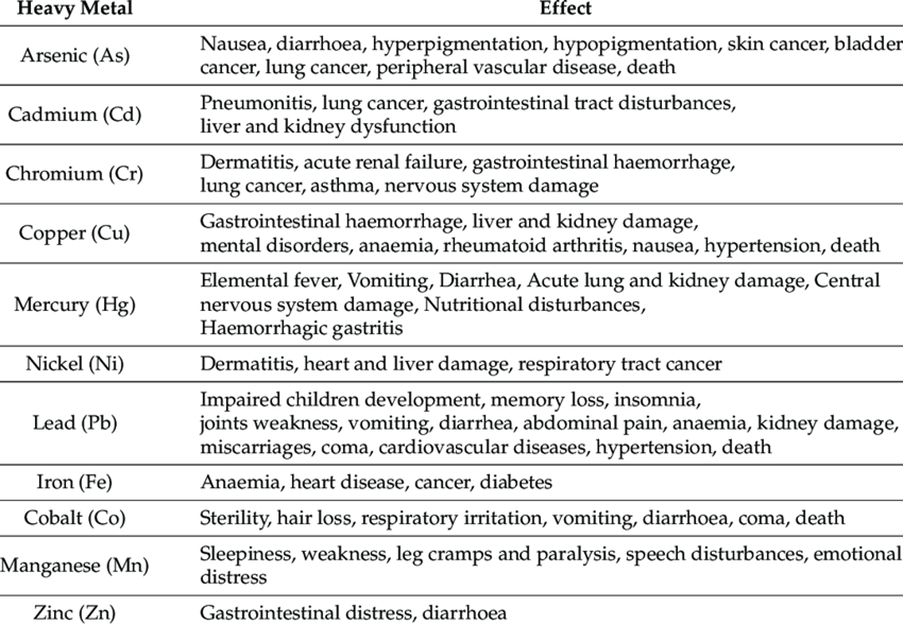

People who work in the industry are at risk of being exposed to chemicals. For example, in the textile industry, workers have access to the chemical naphthyl amines elevates the risk of bladder cancer. Benzene is a chemical that workers who work with rubber are at risk of blood cancers. Exposure to asbestos increases the risk of lung cancer and mesothelioma; tumour of the pleura and peritoneum (Cassidy et al., 2010). Additional examples of metals and chemicals that cause pollution, mine effluents, and acid rock drainage (ARD) and their link to cancer in Table 1.

Table 1: A summarised list of heavy metals in the industry and its effect on health (Whitehead et al., 2021)

Poor diet and lack of exercise.

Both lifestyle factors are associated with an increased risk of obesity, Diabetes Type 2, hypertension, and cancer. Obesity accounts for several solid tumours: breast in post-menopausal women, kidney, oesophagus, colon, endometrium (womb), prostate, liver, ovaries, stomach, and pancreas.

Poor diet can trigger inflammation where immune cells called macrophages trigger the release of proteins called cytokines to increase cell division. The pancreas produces more insulin via the insulin growth factor, and fat cells (adipocytes) synthesize more of the female hormone oestrogen. This increases uncontrollable cell division in the breast and womb forming cancerous tumours.

The increase of salt fish increases the risk of nasopharyngeal cancer in developing countries (Cassidy et al. 2010). Another example is red meat which includes beef, ham, sausage, hot dogs, and salami (Nunez, 2024). The method in how red meat is prepared, processed and even overcooked can trigger cancer incidence. Examples of processing techniques are salting, smoking, curing, or canning where chemicals are used. For instance, smoking meat requires polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). Industries where people handle carbon or crude oil, or substances made from them any industry involving combustion, such as smelting (Cancer Research UK, 2023c). Another carcinogen used is nitrite for curing meat. High levels of processed red meat increase stomach, colon, and breast rectal cancer (Nunez. 2024).

Overcooking meat and starchy food such as chips at high heat via the grill or pan-frying can increase the production of carcinogens: PAH and heterocyclic amines form mutations and increase the production of acrylamide by damaging DNA and induce cell death according to the Food and Drug Administration (Nunez, 2024).

Sociodemographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status)

Some cancers occur more frequently in one sex than another, for instance, men are more at risk of bladder cancer than women because of innate differences. The elderly are at risk due to lifestyle factors, slow immune response, and risk of DNA mistakes (mutations) by chance during cell division or the body has been exposed to carcinogens, such as cigarette smoke (Liver Cancer UK, 2022). However, some cancers occur when young. People in poorly developed countries are more at risk because of the awareness of cancer, accessibility, affordability and transport towards healthcare services contribute to the incidence. Table Two presents the association between sociodemographic factors and various forms of cancer in the United Kingdom.

Table 2: An overview of the age, gender, ethnicity at risk for most cancers in the United Kingdom.

Overall, the increase in cancer risk is a combination of more than one factor that alleviates the incidence, for instance, genetic mutation and lifestyle factors. The earlier the cancer is detected, the more available treatment options can be incorporated within the care planning.

References

Aldouri, A.Q., Malik, H.Z., Waytt, J., Khan, S., Ranganathan, K., Kummaraganti, S., Hamilton, W., Dexter, S., Menon, K., Lodge, J.P., Prasad, K.R. and Toogood, G.J. (2009). The risk of gallbladder cancer from polyps in a large multiethnic series. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO), 35(1), pp.48–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.036.

Ballinger, A. and Patchett, S. (2003) Saunder’s Pocket Essentials of Clinical Medicine. London: Elsevier.

BloodCancer.com (2020) Racial Differences in Blood Cancer Available at: https://blood-cancer.com/clinical/racial-differences (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Brooker, R.J., Widmaier, E.P., Graham, L.E. and Stiling, P.D. (2008). Biology. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Byrd Cancer Education & Advocacy Foundation (2024) Understanding Bone Cancer in Diverse Communities Available at: https://byrdcancerfoundation.org/understanding-bone-cancer-in-diverse-communities/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2017) Bone sarcoma incidence statistics Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bone-sarcoma/incidence#heading-Six (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2022a) First data in a decade highlights ethnic disparities in cancer. Available at: https://news.cancerresearchuk.org/2022/03/02/first-data-in-a-decade-highlights-ethnic-disparities-in-cancer/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2022b) Risks and causes of liver cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/liver-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2022c) Risks and causes of prostate cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023a) Risks and causes of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/acute-myeloid-leukaemia-aml/risks-causes (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023b) Risks and causes of skin cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/skin-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023c) Risks and causes of bladder cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023d) Risks and causes of cervical cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023e) Risks and causes of gallbladder cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/gallbladder-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023f) Risks and causes of thyroid cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/thyroid-cancer/causes-risks (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023g) Risk factors for breast cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/risks-causes/risk-factors (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2023h) Risks and causes of pancreatic cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/pancreatic-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024a) Family History and Inherited Cancer genes. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/inherited-cancer-genes-and-increased-cancer-risk/family-history-and-inherited-cancer-genes (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024b) Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/acute-lymphoblastic-leukaemia-all (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024c) Risks and causes of bile duct cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bile-duct-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024d) Risks and causes of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukaemia-cll/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024e) Risks and causes of kidney cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/kidney-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024f) Risks and causes of mouth and oropharyngeal cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/mouth-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2024g) Risks and causes of eye cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/eye-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025a) Risks and causes of bone cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bone-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025b) Risks and causes of bowel cancer Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bowel-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025c) Risks and causes of stomach cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/stomach-cancer/causes-risks (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025d) Risks and causes of testicular cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/testicular-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (2025e) Risks and causes of ovarian cancer. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/ovarian-cancer/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cancer Research UK (n.d.) Risks and causes of brain tumours Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/brain-tumours/risks-causes (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cassidy, J., Bissett, D., Spene, R. and Payne, M. (2010) Oxford Handbook of Oncology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cheng, K. (2024) Increase in women being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Available at: https://www.womenshealthmag.com/uk/health/female-health/a46968801/pancreatic-cancer-women/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Cleveland Clinic (2022) Ultraviolet Radiation and Skin Cancer. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10985-ultraviolet-radiation (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Delon, C., Brown, K.F., Payne, N.W.S., Kotrotsios, Y., Vernon, S. and Shelton, J. (2022). Differences in Cancer Incidence by Broad Ethnic Group in England, 2013–2017. British Journal of Cancer, [online] 126(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01718-5.

Ellington, T.D., Momin, B., Wilson, R.J., Henley, S.J., Wu, M. and Ryerson, A.B. (2021). Incidence and mortality of cancers of the biliary tract, gallbladder, and liver by sex, age, race/ethnicity, and stage at diagnosis—United States, 2013–2017. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, [online] 30(9), pp.1607–1614. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0265.

Ginsburg, O. and Paskett, E.D. (2018). Ethnic and racial disparities in cervical cancer: lessons from a modelling study of cervical cancer prevention. The Lancet Public Health, 3(1), pp.e8–e9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30233-5.

Guts UK Charity (2024) Bile duct cancer. Available at: https://gutscharity.org.uk/advice-and-information/conditions/bile-duct-cancer/#section-2 (Accessed: 16th April 2024)

Huang, J., Sze Chai Chan, Ko, S., Lok, V., Zhang, L., Lin, X., Don Eliseo Lucero‐Prisno, Xu, W., Zheng, Z., Edmar Elcarte, Withers, M. and Martin (2024). Disease burden, risk factors, and temporal trends of eye cancer: A global analysis of cancer registries. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.14353.

Innes, A. (2009) Davidson’s Essentials of Medicine. London: Elsevier

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2025) Latest global data on cancer burden and alcohol consumption. Available at: https://www.iarc.who.int/infographics/latest-global-data-on-cancer-burden-and-alcohol-consumption/ (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Jack, R.H., Konfortion, J., Coupland, V.H., Kocher, H.M., Berry, D.P., Allum, W., Linklater, K.M. and Møller, H. (2013). Primary liver cancer incidence and survival in ethnic groups in England, 2001–2007. Cancer Epidemiology, 37(1), pp.34–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2012.10.008.

Liver Cancer UK (2022) Risks and causes of bile duct cancer Available at: https://livercanceruk.org/liver-cancer-information/types-of-liver-cancer/bile-duct-cancer/risks-and-causes-of-bile-duct-cancer/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

MacMillan Cancer Support (2020) Causes and risk factors of lung cancer. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/lung-cancer/causes-and-risk-factors-of-lung-cancer (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

MacMillan Cancer Support (2022a) Causes and risk factors of bladder cancer. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/bladder-cancer/causes-and-risk-factors-of-bladder-cancer (Accessed: 16th April 2025).

MacMillan Cancer Support (2022b) Causes and risk factors of Head and Neck Cancer. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/head-and-neck-cancer (Accessed: 16th April 2025).

Mathieu, L.N., Kanarek, N.F., Tsai, H.-L. ., Rudin, C.M. and Brock, M.V. (2013). Age and sex differences in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registry (1973-2008). Diseases of the Esophagus, 27(8), pp.757–763. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12147.

National Cancer Institute (2019) Radiation https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

National Cancer Institute (2024) The Genetics Of Cancer. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2023) What are the risk factors? Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/ovarian-cancer/background-information/risk-factors/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Nunez, K. (2024) 6 Foods That May Increase Your Risk of Cancer. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/cancer/cancer-causing-foods (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Pal, A. and Kundu, R. (2020). Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: The Cervical Cancer Hallmarks and Targets for Therapy. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10(3116). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.03116.

Pancreatic Cancer UK (2024) What causes pancreatic cancer? Available at: https://www.pancreaticcancer.org.uk/information/risk-factors-for-pancreatic-cancer/ (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

Rumgay, H., Murphy, N., Ferrari, P. and Soerjomataram, I. (2021). Alcohol and Cancer: Epidemiology and Biological Mechanisms. Nutrients, [online] 13(9), p.3173. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093173.

Sherwood, L., Woolverton, C. and Willey, J. (2007) Prescott’s Microbiology. UK: McGraww-Hill Education

Skcin (n.d.) Skin Cancer The Problem And Facts. Available at: https://www.skcin.org/skinCancerInformation/theProblemAndFacts.htm#:~:text=Rates%20of%20skin%20cancer%20are%20increasing%20faster%20than,skin%20cancer%20at%20least%20once%20in%20their%20lifetime. (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

University of Oxford (2024) Largest ever UK study reveals stark ethnic and social inequalities in lung cancer diagnosis. Available at: https://www.phc.ox.ac.uk/news/largest-uk-lung-cancer-study-reveals-ethnic-social-inequalities (Accessed: 16th April 2025)

White, A., Ironmonger, L., Steele, R.J.C., Ormiston-Smith, N., Crawford, C. and Seims, A. (2018). A review of sex-related differences in colorectal cancer incidence, screening uptake, routes to diagnosis, cancer stage and survival in the UK. BMC Cancer, [online] 18(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4786-7.

Whitehead, P.G., Mimouni, Z., Butterfield, D., Bussi, G., Hossain, M.A., Peters, R., Shawal, S., Holdship, P., Rampley, C.P.N., Jin, L. and Ager, D. (2021). A New Multibranch Model for Metals in River Systems: Impacts and Control of Tannery Wastes in Bangladesh. Sustainability, 13(6), p.3556. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063556.

World Health Organisation (2025) Cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (Accessed: 15th April 2025)

Wu, E.M., Wong, L.L., Hernandez, B.Y., Ji, J.-F., Jia, W., Kwee, S.A. and Kalathil, S. (2018). Gender differences in hepatocellular cancer: disparities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/steatohepatitis and liver transplantation. Hepatoma research, [online] 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2018.87.

Yusuf, K., Sampath, V. and Umar, S. (2023). Bacterial Infections and Cancer: Exploring This Association And Its Implications for Cancer Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), pp.3110–3110. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043110.

Leave a comment